Laughs and Legends, or the Furniture that Glows?: Television as History

1956 Melbourne Olympic Games

2006 marks the fiftieth anniversary of broadcast television in Australia. It was launched just in time for the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games.

The anniversary has provoked a flurry of events in this country. Among them is a national conference to be held in Sydney on the history of TV in Australia.

With colleagues Joshua Green and Jean Burgess I’ve been preparing a paper for this event. There will be plenty of contributions on the development of the industry, programming and audiences, so the idea we’re working on is not to trace the history of something on TV, but instead to look at television as history in Australia.

No origin; no “it”

One trouble with “television as history” is that it’s not a coherent object of study. TV is one of those things that isn’t really an “it” at all. It doesn’t have an essence, either technically or as a broadcast system, so “it” was improvised, emerging as the work of many hands, individual, corporate and governmental, over a lengthy period.

TV history was and remains strongly national. There’s even a whiff of competitiveness that plays itself out through the public record. For instance Wikipedia plays up the US contribution. There is no doubt that the most influential and widespread forms of broadcast programming and formats, from news to sitcom, originated in the USA in the 1950s. But TV was up and running as a scalable broadcasting system in Europe well before then. Key inventions came from Germany and Britain, while TV as we know it today; i.e. a corporately-owned variety medium playing for leisure consumption in the early evenings to families at home, was launched in Britain by the BBC on November 2, 1936. The US system launched in 1941 (when Europe was at war but the USA wasn’t).

Such national differences mean that any anniversary is pretty arbitrary, even if you concentrate on the launch of broadcast systems as opposed to technical inventions. Thus, 2006 is the 70th anniversary of broadcasting for the Brits; 69th for the Germans, 65th for the USA; 54th for Canada; and so on up to Bhutan, where TV is six years old.

Each of the pioneer countries developed different standards, including internally competing ones. Television was invented twice in various countries, like the USSR, which established electromechanical TV as early as 1931, but then re-started with imported cathode ray tubes in 1938-9.

The context of viewing was also not uniform. The BBC targeted a domestic audience in order to boost receiver sales, which meant in effect that the very first broadcast TV audience was confined pretty much to electrical retailers. The BBC scheduled programming specifically for them during the afternoons, so that they might demonstrate the sets. Meanwhile television was launched in Nazi Germany as a public medium, projected in TV viewing halls.

Australia sat this history out, importing existing technology, system and product. TV was launched in New South Wales and Victoria in 1956. But it didn’t reach the other mainland states until 1959. Tasmania and Canberra waited until the early 1960s and the Northern Territory did without it until 1971.

Academic history

Academic histories of television are less common than you might think, especially histories of programming as opposed to broadcasting systems (Alan McKee has made this point). With few exceptions the academic study of television is stuck in the endless present tense of scientific or policy discourse, pondering questions of effect, behaviour, technology, power and profit.

There are histories, of course, and excellent scholarship, but such work is rarely at the cutting edge of the discipline. Indeed, that is why media scholar Liz Jacka organised the upcoming conference in the first place, because the neglect of television history is especially pronounced in Australia.

Cultural Institutions

Academia is not alone in this regard. Given that watching TV is the most popular pastime in the world and in all history, it is surprising how little the major institutions of cultural memory have taken any notice of it. Museums, galleries and archives that pretend to national status have almost completely ignored it. Television as cultural history is strangely elusive.

On the whole, where they’ve noticed it at all, cultural institutions have not been kind to television. After all these years there is still too much of what Roland Barthes once called “either/or-ism”: Either Cultural Institutions, or the dreaded Tube, viz.:

| Cultural Institutions | TV |

| institutions of collection | medium of diffusion |

| public | commercial |

| memorialise art and culture | memorialise schlock, dreck, kitsch |

| city and civic experience | suburban and domestic experience |

| extraordinary | ordinary |

| art | behaviour |

You know the script.

While the national institutions are a cultural wasteland if you’re interested in popular media, there are specialist museums, archives and cultural institutions. In Australia the National Film and Sound Archive (ScreenSound) has a permanent collection of “representative” TV programming. Its premises in Canberra also feature walk-through exhibitions which include sections on the history of TV.

The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, host of the conference we’re attending in December, is planning a major exhibition in 2006 called On the Box. They’re billing it as “a spectacular exhibition examining the impact of television on the lives of Australians.” We’ll see “The largest collection of television costumes, props and memorabilia ever displayed in Australia!” “Landmark programs and key personalities, as well as studio technology and behind-the-scenes production!” Thought-provoking displays will explore the role of television in the community. Classic Australian clips will show how TV has kept us entertained for five decades”.

Even though such exhibitions are quite rare, they already conform to what Raymond Williams once called “the culture of the selective tradition.” Some aspects of a cultural form are selected over others, such that “the history of television” — where it is noticed at all — is so standardized that it has itself become a genre.

In the process, television usually becomes a symptom of something else. Part criminal, part fool, it stands for our collective fears, desires and follies. If you’re in a serious mood, it’s the history of social and cultural impact (read: negative) or cultural imperialism (read: Americanisation). But meanwhile let’s wallow in nostalgia and see the ads, comedy shows, kids’ TV and sport from, well, yesteryear. Let’s laugh at those hairstyles, cringe at those clothes, wince at how our favourite celebs used to look (pretty bloody awful if the truth be known — why did we put up with them at the time?).

Such topics also correspond to various target demographics: nostalgia and “the history of me” for the oldies; arch critique and knowing kitsch for the urban sophisticates; celebrities and games for the kids.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne is also planning to mark the anniversary. I’ve been working with a group of researchers from QUT to assist ACMI with their plans for this exhibition. It has been fascinating to be involved in the very practical problems associated with trying to make television into history.

Not the least of the issues is a familiar conundrum for any curator or artistic director interested in popular culture — what will persuade people to switch off the TV and come in here to watch TV? It all seems counterintuitive. Immersed as everyone is in popular culture, why would anyone bother to invest time in visiting more of it?

It is really hard — so much so that I haven’t discovered an instance of it yet — to find an exhibition on television that takes the medium and its practitioners just as seriously as artists, photographers and filmmakers are taken in galleries. What would television history look like if it were curated for the Tate modern or MOMA? (If anyone knows an example please tell me.)

1956 Television

The closest thing I’ve seen was the inaugural exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1991, to celebrate 35 years of Australian TV. TV Times was curated by David Watson and Denise Corrigan, and one of its exhibits was a large black box with peepholes through which visitors could spy — as if through an open fridge door and other vantage points — on a suburban couple (played by actors) who sat there watching television (and looking bored leafing through magazines etc.). Very Foucauldian, and an artwork in its own right.

But the MCA collapsed financially soon afterwards and had to be re-launched with a different business plan. Memorialising the popular arts in a serious way seems not to be part of it.

Television on television

There’s an odd but equally standardised genre of TV show that celebrates the history of television.

The very first broadcast in Australia (September 16, 1959) started with announcer Bruce Gyngell (who went on to head up TVam in the UK) saying “Good evening and welcome to television.” He actually did do this. However, the familiar footage that is endlessly re-shown was recorded a year later — to celebrate the first anniversary of Sydney TV station TCN9.

I’m sure Derrida would have something to say about that, but in any case the die was cast. This was how you did television history on television. By faking it. It was simply a matter of promoting the station in question, and if you didn’t have the appropriate materials you just “recreated” them. And on no account did you celebrate the stars, shows or scoops of the opposition.

TV marked its 20th and 21st birthdays with back-slapping gala events in ballrooms packed with personalities. As TV matured and budgets for junketing fell, somewhat, TV history shows moved out of the ballroom and into the archive. The 30th and 40th anniversaries were studio-based affairs, less about the live experience of making television and more about the content screened and the magical moments that television has provided for the delighted viewer. The emphasis was on genre divisions and viewer nostalgia, leavened by celebrity presenters making painful scripted jokes.

In 1991 Channel Nine’s 35 Years of Television made history of its own. It claimed to be the first show that covered commercial TV as a whole, not just one channel. It was presented by stars and personalities from the three commercial networks (although it complained that “the other networks” were reluctant to share their material).

Celebrations for the 50th are already well under way. For instance Kerry Packer’s Nine Network has recently aired a “special” called Five Decades of Laughs and Legends, on the curious grounds that we are now inside the year of the anniversary (tell that to someone who’s 49 and one month!).

As Graeme Blundell (a.k.a. “Alvin Purple”) commented in The Australian, “Five Decades smacks of a grab for ratings desperately — and cheaply — fashioned from the junk pile and the banal hysteria of TV’s supermarket. But despite the less than lofty motives of the networks, the history of TV can’t help being compelling viewing.”

Junk? Banal? Hysteria? Supermarket? Hey — that’s my life! Blundell conceded, however, that “it does illustrate just how far we’ve come since 1956.” Well, yes and no.

Pro-Ams

To fill the void left by “official culture” and television itself there are the amateurs, fans, and the retired technicians and announcers from the heyday of broadcasting. They maintain museums in barns and sheds. They have migrated enthusiastically to the net. They are the “pro-am” consumer co-creators of television history (e.g. the Australian Museum of Modern Media).

The pro-ams tend to fall into two broad groups, organized around technologies on the one hand and programming on the other.

Those interested in programming tend to be the fans and cult followers (to sample, see facts and trivia about iconic Aussie soapie Neighbours).

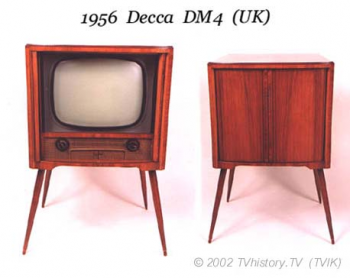

The techies divide between “pros” and “ams.” Professionals are those who have worked in the industry and can discuss details down to the question of whether the electron beam in early cathode ray tubes swept right-to-left or left-to-right. Amateurs are those who love the furniture that glows (Television History: The First 75 Years”).

The pro-ams are proving to be much more interesting and useful to the cause of television as history than the great cultural institutions of memory that soak up the tax dollar. Like eBay their websites make accessible curios that would have been impossible to find before. And unlike “official” curators they’re really interested in TV history, in which many of them have played an active role, on both sides of the screen.

Some of them even seem to be working for broadcasters now. The BBC especially seems drawn to the possibilities .

The future of history

It’s clear that television history is not the work of one agency or even one “discursive regime” (as we used to say). The work of producing it is shared among academics, cultural institutions, pro-ams (including fans and TV professionals), and the history that emerges is different in each case, and in each country.

TV history overall still seems to be mostly “folklore” or “ideology” rather than “discipline” or “science.” Legends are spun that serve the interests of the teller, and these stories tell us more about the source of the narrative — whether a national, cultural, academic, commercial or consumerist speaking position — than they do about television as such.

But as we’ve investigated the cultural memorialisation of television it has also become clear that something new is afoot. The internet offers entirely new possibilities for TV as history, and the number of potential participants in the work of piecing it together has dramatically increased with the inclusion of the “pro-ams.” At the moment the various parties to this work have little in common and less mutual contact. But the future of television history looks a lot more interesting than its past. As they used to say; we have the technology.

Links to more “pro-am” sites:

Early television (treasure island)

Radio history (check out the recommended reading)

House of broadcasting (weird enough for you?)

Museum Victoria (an official site, but nerdily it boasts possessing the “first cathode ray tube television in the southern hemisphere”!)

International

Vintage Electronics Museum (a guy from Hove with a lot of TV sets)

Birth-Of-TV (a European project)

Image Credits:

1. 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games

Please feel free to comment.

OZ TV

I really enjoyed this walk through Australian television. The conference sounds like it would be well worth a trip across the Tasman.

TV criticism into TV history

Also fascinating is ‘Television without pity’ – http://www.televisionwithoutpity.com/ – a website that archives the everyday world of television programming. It writes down not only the content of the shows, but what it’s like as a viewer to watch them.

TV History

I have to agree with everything that John Hartley has said about television history (histories), and this obvious lacunae in the field of media studies. I am currently in the throes of writing (or trying to write) a book with the working title “Television and America: A Social History” and I have through my survey of the current literature been made aware how few serious works there are dealing with this subject in a manner which would satisfy scholars in other fields seeking some sort of guide to the role and impact of television in modern life. Having once embarked on a similar social historical project back in 1974 on movies, I think that I can say that we are at exactly the same position that the academic study of film history was in the early 1970s. The situation can only improve!

critical pro-am TV history?

While I agree with Hartley’s assertions about the lack of a TV history that explores what people do with that amorphous thing called television (particularly in comparison with the academic obsession with instititutional practices and regulatory mechanisms), I am not convinced that pro-am versions of history are any less unfettered by particular codes of fandom, class-based access to technologies and resources, or the selective yet negotiated processes of cultural memory (nostalgia, or its twin, cynicism, often reign supreme on these sites). While I do think that they bear greater investigation and analysis – and should be included in the historical narratives told about television as equally as FCC regulation or the impacts of conglomeration are – I would hope that these sites would receive as critical an analysis as any other. All television practitioners, whether working within the industry, sitting at home on a Saturday night, those getting PhDs on the topic, or those actively producing cultural responses to the medium a la pro-ams, bring particular cultural attitudes, values, hierarchies, codes-of-conduct, and assumptions about what the medium is to bear on the work they do with it. My question is how do we critically integrate pro-am history without repeatedly assigning it “outsider” and thereby, either resistant or duped, status?

Pingback: FlowTV » Speaking to Each Other at Last? The Ghost of TV Past, Present and To Come…

The first television broadcasts in Australia were made in 1934, from the Old Windmill in Wickham Terrace in Brisbane.They were picked up in Ipswich, about 40 km away.

http://www.ipswich.qld.gov.au/.....d_history/

Hi, Nice Information

I am a full internet marketing. I am proud to join this community. I am sure to get useful information to my knowledge. I like leather products because of its superiority in the appeal of other materials. Thank you.

Pingback: Television. Archive.Joshua Green / MIT | Flow

I love that TV design at its best

Im a designer have a look liquidesign

Thanks for the blog

I really liked this television channel the series are really awesome over this website.