When I Grow Up I Want to Be a Boy: Transgeneration‘s Meditation on the “Real”

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY ONE-TIME COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW ARE TAKING SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE FEEL FREE TO CHECK OUT OUR LATEST SUGGESTED CALLS FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

TransGeneration

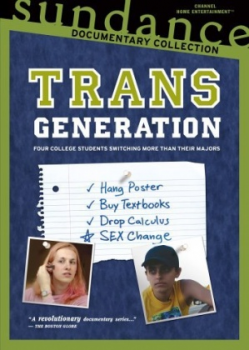

I was sitting on a 42nd street window ledge at the end of a hot New York August afternoon when I looked up and discovered I’d hit the big time. I was on the phone, and my conversation stopped short when I saw the words “Sex Change” on the side of an MTA bus. The ad was in three parts. The middle section was dominated by a simulated sheet of notebook paper featuring a list with three items, “sex change” was accompanied by “financial aid” and “buy books.” A to do list. I looked left, and in bold collegiate type I saw the word TRANS, with the much smaller “generation” below, followed by the tagline: “This fall four students are switching more than their majors.” When I looked to the right, it all came together. The Sundance Channel, in partnership with Logo, MTV’s and Viacom’s new gay-themed cable network, were premiering a documentary series about people (sort-of) like me. The big time.

In the past decade or so, television has slowly embraced a few things gay and, to a much lesser extent, lesbian. By now we are familiar with the rise of Will and Grace, the requisite gay boy and occasional queer girl on The Real World, the fall of Ellen, the pay-cable men and women of Queer as Folk and the L-Word, and the ubiquitous Carson, the blond fashion maven from Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. I raise this short and somewhat narrow legacy of queers on television in order to highlight a looming claim: that being on TV — being represented as a character, fictional or otherwise — brings marginalized people into the mainstream and can be a pathway to some larger, non-TVland, “acceptance.” Was Transgeneration indicative of an extension of this to things transgender?

Transgeneration follows four college students in the United States over the course of a school year: Raci and Gabbie identify as male to female transsexuals, and T.J. and Lucas were born into female bodies and identify as male. They come from different places and socio-economic backgrounds, a fact of which we are reminded each episode, and attend different colleges — Cal State Los Angeles, University of Colorado at Boulder, Michigan State, and Smith College — but according to the show’s opening sequence, they share “one life-changing transition.” This transition — the focal story of Transgeneration — is rendered a matter of genes and hormones, bodies and minds, the movement from one place on a gender binary to the other, opposite place. The series promo features close-ups of one young person after another addressing the viewer: “When I grow up I want to be a (insert profession),” until the last two — a white person who appears to be male ends the sentence “a girl,” and a white person who appears female and wants to be “a boy.” This is presented as both the show’s captivating oddity, and its primary conceit — that being transgender is no more and no less than being anything else, a doctor, a lawyer, a man, a woman.

Characters from TransGeneration

This, of course, presumes that “man” and “woman” are relatively stable categories, even within the expansive picture of who-counts-as-what that is central to Transgeneration’s theme. It also presumes that viewers will know how to identify what is male and female when they see it, thereby allowing them to see the man in Lucas and T.J., or the woman in Raci and Gabbie. This stability of already understood and accepted gender categories may be in part a strategy for making the characters’ movement between them normalized and OK. In the show’s opening episode, Lucas is featured early on in his messy on-campus apartment. The camera scans piles of clothes, scattered papers, and copies of Hustler and Penthouse — twice. Perhaps this is intended to demonstrate the ways in which Lucas is constituting his masculinity. Perhaps it is meant to convey his maleness to a larger, likely non-trans, audience. Maybe it’s a little of both. But it all goes without saying — straight guy porn is, for whatever it’s worth, a sure sign of manhood.

Lucas’ maleness as demonstrated through his mainstream straight porn consumption — and other moments of gendered “realness” established through recognizable gestures, behaviors, and codes — should raise some basic questions: why, how, and for whom do these signs operate? If the four people at the core of Transgeneration are made real in their identities — for themselves, but maybe more strikingly for the show’s cable-TV audience — through acceptable, and thereby legible, gender cues, is it because that’s what it takes for Raci, Gabbie, Lucas, and T.J. themselves to be “accepted,” to be understood as some kind of normal? And how is it that the very power structures which define gender expression, gender roles, and gender policing escape notice almost entirely in the episode by episode establishment of these empathetic and representative trans personalities?

In the spirit of the gay-TV revolution, it seems Transgeneration — backed by the alterna-commercial interests of Sundance and Logo — aims to bring the lives of transgender people to a mainstream public, both queer and straight, in an effort to humanize and make real not only its four main players, but some larger affected community. And while there is no question that many trans-identified people experience exactly the kind of linear narrative proposed by Transgeneration — being born into the wrong body and seeking out a transition that will allow them to live their rest of their lives in the sex or gender with which they identify — many of us do not. In light of this, at least two questions remain (on this topic). If Transgeneration and its promoters are seeking to use television representation in its already questionable role as a means to construct a queerness that is straight-friendly, highly consumable, and a path to social approval, what might that cost trans people, like me, whose realities are not represented in the quest to create a viable “normal” transgender person? What might it take away from other possibilities for change — ones that rely not on normalization and acceptance, but on an expansion of ideas of gender and sexuality beyond the framework of, let’s say, Will and Grace — or Happy Days?

Links:

Transgeneration

The Sundance Channel

LOGO

Image Credits:

2. Characters from TransGeneration

Please feel free to comment.

sex and political correctness

Reading this article, Agid makes it clear that sexual liberation cannot be politically correct. In this case, Will and Grace or Happy Days are not exactly the limits.

thanks

I am writing a paper about Transgeneration and its potential to help form limits of what transgender means in the mainstream by defining transgender in terms of heteronormative culture. Of all of the research I have done, this is the first article to bring up any of these points.

not necessarily…

i felt that the representations of TJ blurred and complicated any linear narrative of transition from “wrong” body to “right” body. TJ also complicated notions of masculinity in his subversive ambivalence toward masculine privilege and gender performance. also, gabbie’s story worked to illuminate the falsity of notions that transition is seamless and wholly resolving of gendered identity issues; her overinvestment in transition as potentially problematic was certainly underscored by the editing and interviews with her friends and family. while i agree with your point that larger power structures governing the legibility of gender performance seem to fall to the wayside in much of the show, i feel that the representations of TJ, Lucas, Racy and Gaby did work to complicate notions of gender performativity, identity and the process of transition.