Feeling Blue: Katrina, The South, and The Nation

A little over a year ago, following the heartbreaking outcome of the 2004 presidential election, those of us on the left coast were feeling pretty smug about our difference from Bush country, and, in particular, the South. Buying into the us/them logic of network media coverage, Californians took some perverse comfort in feeling blue. The maps circulating on television and in newspapers fixed state boundaries in inviolate shades of red and blue. If we Angelenos were disappointed in the election results, we could at least feel confident that our state had been true blue.

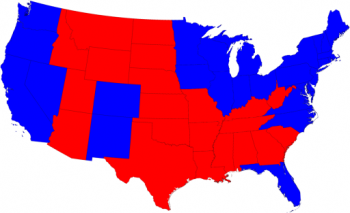

A typical red vs. blue post-election map in November 2004. The solid sea of red does powerful ideological work.

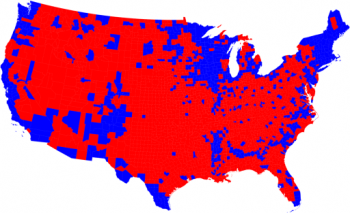

Of course, a more careful analysis of this red-blue binary revealed its limits. Much less-publicized maps appeared on the internet, including maps that analyzed the country by county and by population, revealing as much red in California as in Georgia. But the dominant red/blue logic largely held sway, in part prompted by the simplistic visual field of network news, a signifying economy more than willing to trade in easy-to-read, lowest-denominator graphics. Furthermore, the ease with which this logic took hold across the country (and across party lines) had everything to do with much older cultural narratives that relentlessly fix the South into precise roles in the national imaginary. The United States has long had a bipolar fixation on all things southern, alternately figuring the region as the hotbed of family values and lost grandeur or as the locus of American shame, poverty, and trauma.

An election map broken down into county by county results. This detailed analysis reveals the limits of a red vs. blue analysis.

The recent coverage of the Katrina disaster largely runs along these well-worn grooves of national memory and amnesia. Soon after (and even before) word of the New Orleans’ levee break circulated, national news programs began offering up maps and images of the historic city, speculating on the damage to the French Quarter and other tourist areas. The nation appeared to breathe a collective sigh of relief when it was revealed that these “historic landmarks” had been spared a watery fate. President Bush even felt free to wax nostalgic about his youthful partying on Bourbon Street, asserting that the South would rise again. Folks seemed more concerned about the fate of Preservation Hall, filled as it is with iconic images of a (now) nostalgic, former blackness, than with the Black bodies trapped in rapidly rising water, losing life as time ran out for rescues.

The packaged images of historic New Orleans — so tied up in blackness of another era — operated as a kind of disavowal for the racism that elsewhere was writ large across our screens (and, of course, our social and economic policies.) The images of African Americans “looting” or, alternately, as bereft, tragic, and displaced, should have knocked roughly against the more sentimental portraits of New Orleans’ history as an “unique American melting pot,” but these contradictory images are familiar from many years of southern representation. We are all too capable of holding them in separate frames through the fragmentary, if not binary, logics supported by electronic media, partitioned logics that neatly dovetail with our modes of representing the South.

A typical image from the Katrina coverage. These representations of tragic blackness (or, alternately, of “looting,” chaotic blackness) have long histories in American visual cultural, particularly when imaging the South. In a southern context, they work to locate American racism “elsewhere.”

This national schizophrenia about the South is possible precisely because America has refused to come to terms with our racial and racist pasts, cordoning them off as a kind of regional problem always located elsewhere. Such a partitioned mode of thinking characterizes post-World War II, post-Civil Rights discourse, proliferating binaries of rural/urban, red/blue, white/black, and us/them. It allows us to forget that the disaster in New Orleans and along the Gulf was possible precisely because the nation has abandoned its domestic infrastructure, neglected the poor, and failed to realize the hopes and possibilities of the Civil Rights era (not to mention the Emancipation era.) This failure affects the South and also the nation. As I watched, spellbound by television as portions of my home state flowed into the Gulf, I knew that, despite the red/blue binary, the problems of New Orleans are also the problems of Los Angeles. Those detailed election maps remind us that our voting patterns aren’t that different either.

During the past several weeks, alternative scripts have sometimes surfaced, particularly given the media’s imperative to give us chaos coverage 24/7. Local reports here in LA noted that many displaced African Americans headed west to Los Angeles to reunite with family members, inadvertently highlighting the diasporic patterns of southern blacks across the history of 20th-century America. Of course, coverage of natural disasters (or of urban rebellions) hits close to home for Californians, living as we do on multiple fault lines, both real and imagined. Various local media streams came close to sketching the possibility of sameness or reunion in imagining La. and LA as somehow similar, even if these images were largely fleeting ones. Nonetheless, I take these as hopeful signs, a kind of implicit recognition that regions travel in unexpected ways and that commonality might be found in the least predictable of places. It’s a mapping I vastly prefer to last year’s red and blue one. Still, we’ll be hard pressed to gain from these moments of possible union if we continue to repress the knowledge that the South is dispersed across the nation and that its racial histories overdetermine every aspect of this American life.

See Also:

Douglas Kellner — “Hurricane Spectacles and the Crisis of the Bush Presidency”

Tara McPherson — “Re-Imagining the Red States”

Image Credits:

1. A typical red vs. blue post-election map in November 2004

2. An election map broken down into county by county results

3. A typical image from the Katrina coverage

Please feel free to comment.

Interesting article, however, when discussing Katrina and Southern racial politics why not include Mississippi into the midst?

Pingback: FlowTV » TV in the Season of Compassion Fatigue

Racial hierarchy revealed

I thought one of the most interesting points in this article was the realization that “Folks seemed more concerned about the fate of Preservation Hall, filled as it is with iconic images of a (now) nostalgic, former blackness, than with the Black bodies trapped in rapidly rising water.” This realization points out our that our nation has still not achieved true racial equality, evident here in that the white-dominated media was more concerned about the preservation of ideological icons of black progress toward equality than about actual living black victims of the hurricane. It brings to light the fact that the racial hierarchy within the United States is still very much alive and enduring. The media’s focus on the fate of Preservation Hall seems to be a nationalistic fallacy with its basis in the existing racial hierarchy of the United States, in that the nation cares more about its ideology supporting the equality of its nonwhite citizens than about its nonwhite citizens themselves.

the south will rise again, and other matters…

It’s interesting how our views of the South change from time period to time period. Until recently, the South had been pretty much ignored and left to itself as just another Republican territory, but once Hurricane Katrina hit, our perceptions changed as we began to realize how racial inequalities still exist. The media coverage of the natural disaster made it blaringly clear through the “looting vs. finding” controversy, and its choice of who it covered on tv footage revealed the racial and class inequality still persistent in today’s society. This just serves as a reminder that we’ve still got a lot to change about our social system.

What about the others?

I strongly agree with the article’s menttion of the racial ‘black/white’ binary discourse that has become regionalized in this nation throughout our history. However, it is particularly because of this limiting binary that we tend as a nation to either forget or ignore the existence of other minority groups thatwere also affected by Hurricane Katrina. While the media was busy airing stories about the physical condition of Louisiana’s historic grounds or about how blacks were found ‘looting,’ little or no coverage was done on other minorities affected by Katrina. One story in particular that was only aired in Spanish networks but that should’ve received English coverage was about the large number of Hispanic immigrants that due to language barriers or fear of being deported, didn’t seek assistance and are now among the many missing andfeared to be dead.

A Color-blind Nation

Agreeing with the article, the South does disregard its racial history and is a perfect example of how our nation has developed a false color blindness by pretending race no longer holds impact on society, when everyone is continually affected by race. Ignoring race as a factor of recent national political issues like those dealing with Katrina, is the same as forgetting the history that has developed them. When seeing images of black people affected by the disaster we should not blame them for their misfortune, but blame our color-blind nation that has forgotten its racial history and which will endure the future effects as its result.