Teaching Television, or What I’ve Learned From Flow

by: Derek Kompare / Southern Methodist University

This point of the summer sees most of us academics out of the classroom, but not too far out of it. Sure, we’re taking advantage of relatively open time to research, read, write, revise, clean house, watch DVDs, play with our kids, catch up on our McSweeney’s,and maybe even take a bona fide vacation. We’re also prepping our fall courses.

This summer, more than I have in a while, I’m rethinking how I teach television. More specifically, I’m rethinking that most vexing of classroom ventures: the first-year core course. Usually denoted by the portentous labels of “Introduction,” “History,” or “Survey,” these courses are our programs’ front doors. Ideally, they prepare most of our students for the rest of the curriculum, providing them with a base of useful knowledge and skills and an awakened sense of inquiry (while the rest reconsider that Business degree that Mom and Dad advocated). While core courses can and do work this well, they may also function in a much less engaged mode, taught and experienced cursorily (even reluctantly) as a rote journey through well-worn chapters and exams, with about as much intellectual engagement as a trip to the dentist.

We, especially those of us on the near side of tenure, are often inclined or guided (indirectly or frankly) towards this latter approach, albeit for perfectly valid reasons (those articles aren’t going to write themselves, after all). The narrower, deeper, and ostensibly “richer” soils of our upper division and graduate courses seem to present more tantalizing pedagogical opportunities. Moreover, this perspective is often shared by our students (and, it must be said, more than a few academic advisors) as these courses are nakedly regarded as “stuff to get through” before moving on to “the good stuff.” The resigned acceptance of these mutual expectations, hovering in the classroom sometime during the first week of the term, is one of the saddest, yet predictable, moments in US higher education.

Heading into my seventh year on the tenure track (at two different universities), and my (gulp) fifteenth teaching undergrads, I’ve realized that I’ve fallen into this rut. It’s not that my techniques are ineffective or outdated, or that my evaluations are low; they aren’t. It’s more that that vital spark has diminished. Even though I’ve only taught this particular class for two semesters (I’ve only been at SMU since last fall), it has become something to “get through” as much for me as for my students. It didn’t help that the textbook I hastily chose last spring was more of a burden than a benefit, or that the Frankensteinian merging of new material into old lectures didn’t always work. In resigning myself to these resources, I had already lowered my own expectations.

While this problem afflicts any teacher, at any level, in any field, it’s particularly troubling in Media Studies. How can we fail to engage students in media culture, of all things, the very thing that’s ostensibly been distracting them from their “real” studies their entire lives? Perhaps, in our zeal to weed out the kids who think it’s a class where you “like, watch TV,” we’ve overcompensated, turning media into our joyless projections of, say, Organic Chemistry (“This is a Serious Field.”).[1] You go too far down that path, and suddenly it really is joyless. Television Studies’ tenuous disciplinary status adds to this uncertainty. Our field is ably represented in a wide variety of academic departments across the humanities and social sciences, with widely differing institutional norms, expectations, and conditions, which almost always differ from those we were trained in. Our successes in producing our television curricula in these wildly disparate (and sometimes difficult) situations don’t often come easily.

So, in rethinking this course from the ground up, I’ve consulted the experts: I’ve read the entirety of Flow. In the process, I think I’ve found what I’ve been missing (or, had at least misplaced lately) in my television teaching: passion. Not my passion for television per se, but the communication of that passion, that urgent press of big questions and big ideas, powered by big intellectual enthusiasm. This passion, redolent on Flow, is generally infused with the forms and styles of both scholar and subject. I know many of the “Flowers” personally, and can easily envision their animated, somewhat caffeinated delivery behind various conference podia. But there’s more going on here. In text alone, so many articles have effectively conveyed the very “TVness” of Television Studies, as the paedocratic play long suggested by John Hartley (and pursued most effectively by resident chef/Benny Hill fan Anna McCarthy); the civic engagement presented variously here by Michael Curtin, Faye Ginsburg, Tom Streeter, and Fred Wasser; the mediated wonder explored by Brian Ott and Robert Schrag; and myriad other senses. Like the best diaries on your favorite blog, or just about anything by Frank Rich, Flow articles are compact yet powerful; in classroom terms, they’re the kind of mini-lectures you deploy to incite your students on sleepy Thursday mornings in November or April.

This kind of passion, effectively worked into the course, can puncture the core-course blues, and eviscerate two common student reactions: knee-jerk indifference (“it’s just TV”) and knee-jerk hostility (“TV bad”). The former attitude is usually shorthand for “don’t make me think,” while the latter generally boils down to “everything mainstream is shit and we’re all doomed.”[2] Well-directed passion complicates both positions, by revealing television to be more complex and engaging than either allows for. It destabilizes the process of dismissive generalization, and ignites interest in the grit of TV: cinematography, gender representation, issue framing, corporate mergers, etc.

Reading Flow has also reinforced my primary teaching point about media (not just television): media is always social. It is produced and consumed (to tailor a massive range of activities down to the standard binary) by people, in groups, and as individuals. As a teacher of potential media-makers, and certain media-users, I feel the connection between the media world and conscious thought cannot be overstated.[3] Regardless of what you think about Lost, Chappelle’s Show, or Beauty and the Geek, people make them, people distribute them, people watch them, and people discuss them. Media texts, systems, and meanings are actively produced by actual, living, breathing people. Giddens’ structuration theory is most helpful here, as James Lull suggests, in that it identifies structure and agency as key components of contemporary life, but, critically, does not simply pit them against each other.[4] Neither is purely “good” or “bad,” but both are essential to modern survival. And there is no better proof of it in action for the intro course than the judicious use of TV itself, in its specific contexts, warts and all, as myriad Flow examples indicate. Reading Cynthia Fuchs, Heather Hendershot, Allison McCracken, Jason Mittell, or Mimi White explore particular genres and programs has reminded me that the best criticism explodes its subject like a firework, creating dazzling insights and connections. Emphasizing television’s social nature helps bolster the importance of all sorts of approaches, whether cultural, regulatory, industrial, historical or aesthetic, not as abstract categories and dry lists of terms, but as networked nodes of significance.

Along the way, passion should also be instilled in the assignments. Yes, students should know some specifics about the formation of RCA, and the Prime Time Access Rule, and the difference between a rating and a share (and yes, they will all be on the test; don’t forget your Scantron forms). However, assignments, even exams, should inspire and gauge passion and engagement. Accordingly, I’m ratcheting up the writing component a bit for this class (though still well short of burying my desk). My students will actually generate the topics of much of these writing assignments the first weekend of the semester, as I’m taking a preemptive strike towards understanding their media worlds; Gen-Y lifestyle pieces from the Times or market analyses in Madison & Vine alone can’t cut it. If they don’t watch Survivor anymore, or don’t know who Gilda Radner was, or have their entire music collection on their iPod, I want to know up front.

One last suggestion for the intro course, inspired, indirectly, by the so-called Fiske-McChesney debate on this site. Passion is critical, but so is reason. The two are the yin and yang of our profession. For what it’s worth, as one of those Vilas grad students caught “between” John and Bob in the 1990s, I believe each had, and has, copious passion and reason. Each questioned preconceived attitudes in their respective fields, and each has produced a body of challenging, passionate scholarship. Moreover, each reminded us that the world beyond the screen (whether “behind” it or in front of it) is what we’re really about. Thus, like Bob and John, I think it is incumbent on us to continue to explore the relationships between mediated and “real” reality in the intro course, not solely to catalog their “gaps,” but (perhaps more importantly) to explore their resonances. How, precisely, does 24 inform our understanding of national security practice and American national identity? How do the umptillion police procedural series on the broadcast networks shape our sense of the real criminal justice system? What are the relationships between the physical and mental upheavals of reality television and the lack of news coverage of important real suffering? How is the encroaching digital shift changing our social relationships? How do the mainstream news media and the blogospheres produce several divergent socio-political realities?

There’s still enough summer left to enjoy, but I have to say… I’m looking forward to the fall.

Notes

[1] No offense; I’m sure organic chemists are plenty joyful.

[2] I’ll add here that veteran teachers can spot the purveyors of said attitudes a mile away.

[3] This is certainly not to disregard the importance of unconscious thought.

[4] James Lull, Media, Communication, Culture (New York: Columbia UP, 2000) 8-9.

Image Credits:

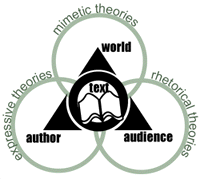

1. University College Northampton

2. Studies Triangle

Please feel free to comment.

Really useful reflections

I enjoyed reading these reflections on teaching introductory (or, whatewver) courses on television. In fact, it is my experience that teaching television demands more reflection or re-consideration of what has gone before, It is usual to begin over again for every new year of teaching–I probably dump 40-50% of what I did before, and start my second year TV course with “The Future of Television” (rather than in its usual final lecture slot)–arguing that things may well have changed in TV by the time we come to the end of 12 week teaching block. I also get my students, as their first assessment task, to write ‘A Personal History of Television’, after telling them my own history. This establishes, from the beginning, that talk about television is about experience and and life-long engagement. It also enables me to reveal my own taste formations, biases, prejudices etc–and reinforces my contention that teaching about television can never be a value-free enterprise.I do teache about ratings too–but from a fairly critical perspective.best wishes from Down Under

Geoff Lealand University of Waikato, New Zealand

resonance

Kompare’s discussion of the potential pitfalls of teaching television deeply resonated for me. In the past, I have walked into my classroom with a “this is not a class where we will only watch The Simpsons” chip on my shoulder. I have indeed tried to impress on my students that the class was serious, that just because they watch television they know everything there is to know about it. I even composed a lecture for the first week on the history of radio regulation to scare off students who had thought the class would be easy.

So I greatly appreciate Kompare’s reminder that one of the main reasons to study television is that it has a personal impact on us, and that it is a medium of tremendous social importance.

One of the questions I have for more seasoned television instructors is how to strike the balance of teaching students to think critically while at the same time acknowledging their personal relationships to texts? In other words, how can we reconcile being critical of the messages encoded in texts with the pleasure taken from them?

responding to resonance

Along with Kompare, I find myself greatly appreciating Flow. On a simple level, it lets us know we’re not the only ones doing the job, or wrestling with these issues.

As my own humble response (and from one who is hardly ‘seasoned’) to Allison Perlman’s question, I think the most important thing is to *model* the critical-yet-pleased response. Perhaps too many TV teachers despise TV, and if they have “passion,” it’s driven by pure dislike. This hellfire-and-brimstone position gets the students’ attention, but I’m not sure how much it resonates with them, at least in the long term. I find that many students appreciate a prof who loves some things about TV, and honestly reflects on that, yet will complain and criticize with impunity when required. It’s almost as if liking at least one program ‘buys’ me the right to criticize without just seeming like another angry, burnt out prof

Pingback: FlowTV | Television’s Aesthetic of Dead-Ness