Terrordome

by: Cynthia Fuchs / George Mason University

The Shield

Mackey has the manner of someone who might erupt, geyserlike, through his bald pate at any moment.

— Jon Caramanica, New York Times (13 March 2005)

I grew up with criminals. I grew up with dope dealers and guys who are now in jail and dead, and I don’t condone their behavior, but I understand it.

— Ving Rhames, Daily Herald (20 March 2005)

USA’s new Kojak loves the baldness. From frame one, Ving Rhames’ shiny head fills space and throws back light. Yes, he’s got the expensive suit, the badge and the damn lollipop, but the point is plainly that great, portentous cranium.

It’s not even nostalgic, the head, though it does nod to the olden days, when Telly Savalas ruled tv’s New York (1973-78), when gritty realism was a matter of careening cars, cocky gangsters, and cops with catchphrases. Today, realism is more elusive, an assortment of disparate, sometimes irresolvable elements, terrorists, multi-generational and international gangs, and psycho-killers, raging their ways through downbeat plots and convulsive handheld camerawork. All this commotion leaves cops — those longtime purveyors of tv realism — a bit adrift. They’re no longer necessarily upright or even coherent. Now, as Kojak‘s pilot (25 March 2005) made clear, they’re as likely as criminals to be abusive and selfish, afraid and shady.

Welcome to the Terrordome. It’s different now, not so much a PE-style retribution as a constant condition. After 9/11, tv cops have struggled to matter, to make their earnestness relevant and their science effectual. Mostly, they’ve turned repetitive and self-absorbed: the Law & Orders and the CSIs are surely somber and forensic, and sometimes they’re even perverse (see the recent glut of child molestation and fetish sex storylines), but they’re also comfort food-ish. Because network tv isn’t in the business of disquieting viewers, it’s perennially behind on scary or potentially controversial curves (even 24‘s recent dip into torture by supposed good guys like Jack Bauer and the Secretary of State isn’t as alarming as it might have been even last year).

Enter basic cable. Caught between network and premium cable, USA and FX mean to rile consumers, win Emmys, and, of course, make money. The route to such lucrative upset is convoluted, of course, as demonstrated by Kojak and The Shield — both featuring notoriously bald, bombastic tough guys who ignore rules when it suits them. Operating on opposite coasts, in NYC and L.A., Kojak and Vic Mackey (Michael Chiklis) embody and exacerbate the tv cops’ present dilemma. Called on to protect their “communities,” they’re faced with all manner of cunning, brutal, hopeless criminals. The streets seethe with menace and madness, and no matter how quickly they respond, the cops are repeatedly too late. Borders are broken, home lives ruined. They lie and cheat, fight amongst themselves when they’re not fucking each other, resent the arrogance of their adversaries and feel so defeated by the system they’re supposed to uphold that it hardly seems to matter what they do.

Tellingly, both Kojak and The Shield have found similar means to make their mad bald anti-heroes even remotely sympathetic (they’re not in Deadwood, after all). And that route goes through kids. Whatever they do, they protect kids — from lousy parents, from sexual abuse, from drugs, violence, confusion, and horror. Kojak has already spilled his guts on a rationale (his jazz pianist father was murdered in a diner when Kojak was a child), and Vic, who apparently never had a childhood, has ongoing kid issues (his son is autistic, his daughter is acting out over his impending divorce).

For all their similarities, Vic and Kojak appear to handle their kids concerns differently. For Vic, it’s one of many motivations for brutality: When he hears that some child has been raped, turned into an addict, prostitute, or mule, Vic implodes, all steamy meanness, his symptomatic sense of entitlement ignited. During the fourth season premiere, “The Cure,” he’s furious at being condemned to desk duty for infuriating his outgoing captain, Aceveda (Benito Martinez) once too often. Holed up in what used to be called the Strike Team’s “clubhouse,” literally surrounded by videotapes of a custom cars sting, Vic finally finds his catharsis. He sees a child beaten by his father, one of the sting targets, and hauls ass to a bar where he goads the guy into assaulting an officer. Vic mashes his face in.

When he tries to slide it by his incoming captain, Monica Rawling (Glenn Close), she busts him. She knows where he’s been, what he’s done, and exactly why he’s untrustworthy, matching his every canny and cynical move. Suddenly, Vic is looking less adroit, more eager to please. And so he tries another move, contrite and committed: he’ll do whatever she wants, if only she’ll let him head up her new gangs task force. It’s an assignment made for him, he blusters, he’s gotta have it. His face goes taut with desire and conniving.

Alternating between child protector and childish bully, Vic is an uncomfortably representative post-9/11 tv cop, grasping, self-righteous, needing to be right, even if this means making up motives after the fact. His uneven parallel might be found in Aceveda, who was raped last season and is unable to make sense of this ritual unmanning. His responses have been multiple and horrific: more determined than ever to punish Vic, he’s also alternating, between empathetic father confessor/interrogator of a rape victim (in a scene that frames the room’s church window between him and the woman) and trauma victim, using this same woman’s victimization — a surveillance tape of the assault, ugly, obscure — as his personal pornography. It’s an awful moment, certainly rare on television, where rape tends to be done to women, who fight back on Lifetime.

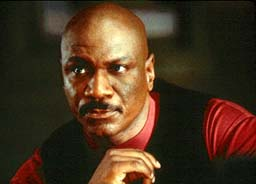

Ving Rhames on Kojak

Kojak brings another sort of trauma to his table, in part resonating from his father’s death. He identifies immediately with a boy whose prostitute mother has been tortured and murdered by a serial killer, then spends montagey quality time with the boy and his sister, giving them lollipops in the park and ensuring their car thief dad’s release from prison. At the same time, Kojak relentlessly pursues the murderer, who turns out to be two: first, the traumatized serial killer (when pressed to produce “evidence” of his culpability, he sneers, “I am the evidence,” meaning, it’s really his prostitute mom’s fault); and second, a cop who challenges Kojak to take him in, as this would mean undermining any number of his trumped-up evidence cases. Seeming stuck (he cries), Kojak takes an unexpected option, getting vigilante on this smug bad detective’s ass.

These cops do save kids. That their methods include murder, deceit, and transgression only makes them part of the current zeitgeist. They’re symptoms, products, and purveyors of terror.

Image Credits:

1. The Shield

2. Ving Rhames on Kojak

Links

More from Fuchs on Kojak at PopMatters

Ratings report on Kojak premiere

Fans of The Shield weigh in

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Week on Flow

Children vs. Family

It is interesting to note how this idea of supporting children plays out in Vic’s more devious activities on prior seasons of The Shield. For instance last season, robbing the mob of millions of dollars was consistently juxtaposed with the fact that Vic would need extra money to support his autistic son. However, Vic is clearly not a family man in the traditional sense, his constant cheating is leading to a divorce. In light of the Christian right’s power in the post-9/11 landscape, what is at stake in refashioning familial loyalty to commitment to children only in this more “adventurous” cable setting?

no rules

I can’t say I’m too surprised by the current trend of renegade cops featured on television today. I think their prominence can be partly attributed to post 9/11 zealousness, but I think it has more to do with the constructs of the cop shows themselves. I think that the protagonists are shady, dishonest and cruel because it makes for a larger audience for the show in question. TV audiences have long since grown tiresome of the by-the-book police officer, and to make a show about one would probably be a disaster. One of the reasons that gangster films as a genre find a considerable audience is that people admire others who live and act by their own rules, right or wrong. This template has been applied to that of the police officer, only now the protagonist can be admired moreso because he is doing vile and dishonest acts under the umbrella of “good”, essentially acting with no consequences or rules bu his own.

The narrative of Cop shows

The television cop show has very historic and early roots. From Dragnet to The Shield, the television cop has been a mainstay on television for over half a decade. As Fuchs states, the current trend of the renegade cop to act out in terror and fear is representative of the times in which the show is produced. As police officers these characters have sworn to serve and protect, to uphold the law. But their role as civil servants is framed within the society that they protect. In the 1950s Dragnet showed crime and society in a sterilized vacuum. Everything was always resolved within the timeframe of the show and the central figures always maintained an air of omniscience. Never would the “criminal” out-smart our purveyors of justice. As society becomes more weary and skeptical of the government which we appoint, questions of authority also arise. Those that always felt safe here in the U.S. boarders felt betrayed post 9-11. Those which loathed the government saw this as an opportunity to point out all the weaknesses and faults in the structure of our protecting body. Many citizens simply feel that the sugar-coated Superman version of policing forces is no longer relevant. Kojak and Vic are representations of the anxieties and fears, albeit hyper-exaggerated, of the current society. They are untrusting, unrelenting and uncompromising. A modicum of trust is only afforded to those which are still routinely depicted as genuine and pure: children. Children are still thought of as uncorrupted, not yet soiled by the harshness of reality. Perhaps this is why both these grim and gritty characters seem to respond to children. Children are still given the benefit of the doubt; often they are placed in situations where they had no opportunity to change anything by their own accord. One could make the argument that children still represent the hope and unblemished future, one that seems so bleak in these cop shows. But how else could these shows be portrayed? Better this than the sterilized and perfectly functioning world of Dragnet. Or perhaps these shows simply are trying to get at a more realistic characterization of the “cop” This is a subjective statement to be sure, however in any situation isn’t more information always preferred? Better to have more facets of personality in your central figure, although unflattering and distasteful as they may be, than a simple cut-out Captain America type. Many would argue that Batman, a detective as well, is a far more interesting character because he is not black and white, the world he lives in is grey. That is where we are, a grey ill-defined world. No wonder that vigilante justice is so popular. Everyone has their own interpretation of what is right and wrong. Yet despite all this, family, in the form of children is still a central theme. Police have to make some difficult choices everyday, but in the end it is their job to protect those who cannot protect themselves.