The Copyright Creative Stranglehold

by: Patricia Aufderheide / American University

Veteran filmmaker David Van Taylor spent months following one-time Contragate schemer Ollie North on a political campaign for his film, A Perfect Candidate. At one stop, he caught North surveying the crowd singing and swaying along to a singer intoning, “God Bless America.” He had to pay the Irving Berlin estate several thousand dollars to use the song.

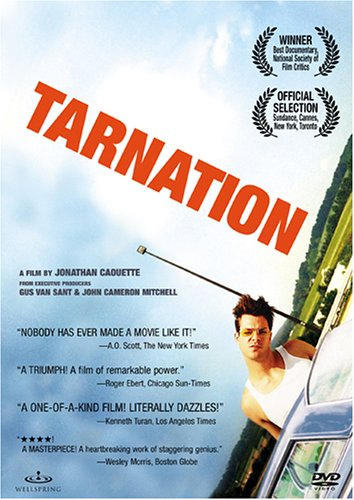

Budding filmmaker Jonathan Caouette spent $218 to make a movie on his Macintosh about his dysfunctional family, Tarnation. It went to Cannes and was released in theaters. But because the film interwove with images of his family many references to popular culture — each of which had to be cleared with the copyright owners — the film ended up costing $400,000.

Getting a copy of Eyes on the Prize, the classic documentary series on the civil rights movement, has turned into an e-Bay hunt for librarians. Why? Because rights to the many quoted images and sounds in the historical series have expired, and would cost more than $500,000 to re-license. The series is no longer in commercial distribution.

These are only three examples of the outrageous consequences of today’s interpretation of copyright law discovered in a report my co-author Peter Jaszi and I just completed at American University, “Untold Stories: The Creative Consequences of the Rights Clearance Culture.” They testify to the fact that unbalanced interpretation of copyright leads to a creative stranglehold.

Filmmakers must pay a license to use a pop song that may play in the background in a pizza parlor, an image or sequence from a movie, or from archival footage owned by someone else. They may need to pay not only songwriters but performers, not only movie studios but actors. There is no central place to find out who owns what. There is no rule of thumb for pricing. No one has to agree to license. And it doesn’t matter if you didn’t intend to quote it. Did somebody sing “Happy Birthday” in your documentary? Too bad — you owe Time Warner a small fortune.

A system that has a logic — it’s fair to pay others to use their work — is spinning out of control. The copyright stranglehold has been tightening over the last decade, as media consolidation has also consolidated control over film and photo archives. It has also been driven by big media companies’ fear of digital copying. Copyright, which has always contained rights for users as well as for owners, has increasingly been tilted toward the rights of owners. Rights of users, such as “fair use,” are getting harder and harder to use. (“Fair use” is guided by one general concept: Do the public cultural benefits of the use outweigh the private economic costs?)

The copyright creative stranglehold may be strongest where it is hardest to see: on the imagination itself. The strictures of copyright clearance today make documentarians avoid social criticism, cultural commentary, historical films, satire and parody.

“The biggest problem is self-censorship,” said filmmaker Jeffrey Tuchman, who regularly works for the major cable networks. “You don’t try what’s not possible.”

What’s not possible is decided by the people who show documentarians’ work — especially broadcasters and the all-important errors-and-omissions insurers. They avoid the very whiff of litigation, even frivolous litigation. And so balancing features of the copyright law, like fair use, simply are ruled out.

At the same time, some filmmakers are fighting for their rights, including the right to fair use. For instance, Robert Greenwald successfully asserted his right to quote Fox News without license fees in his documentary Outfoxed.

The problems faced by documentary filmmakers are also faced by book authors, musicians and other artists. But because documentarians both want copyright, as a protection for their own work, and also need to quote other people’s work, they have ended up, willy-nilly, on the front lines of a battle for the right to quote and comment on our own culture. No digital-era solutions (Internet-fed distribution for example) work without the permission to quote material that somebody already owns.

They may also become part of the solution. The study shows that artists who understand copyright law better — especially its balancing features — have more creative freedom, and that more education of creators and gatekeepers is critical. Furthermore, filmmakers already have some common ground to assert standards for fair use in documentary filmmaking. The Center for Social Media is now coordinating the formation of a collective statement by documentary filmmakers of best industry practices around fair use. This can become a valuable tool for negotiating contracts and even in the courts.

For more information on the Statement of Best Practices, go to The Center for Social Media, where you can also find the full text of the report “Untold Stories: Creative Consequences of the Rights Clearance Culture for Documentary Filmmakers,” a project of the Center for Social Media and the Project on Intellectual Property and the Public Interest at American University. A free DVD that includes a 7-minute film and the study is available simply by emailing

Links

Tarnation trailer (Quicktime plugin required)

Image Credits:

1. Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Week on Flow (April 15, 2005)

Copyright Clearance

Pat Aufderheide’s article points out an interesting limitation on filmmakers that deserves more critical attention. I think her critique of the copyright clearance system can also be extended to narrative films, especially indies. I saw a wonderful German film called Paul is Dead at Slamdance in 2001 that will never be commercially shown in the U.S. The film is about a 12 year-old boy who discovers the conspiracy theory that Paul McCartney died in a car wreck and is replaced by a look-alike. Of necessity, the soundtrack includes many Beatles songs, the rights to which are ridiculously expensive. The film was shown for free at the festival, but could not be commercially distributed without the acquisition of the rights to the songs. It would be ideal to find some happy medium between paying artists their due for their works and allowing other artists fair use. One would think that the continued use of an artist’s work would be preferable to the exorbitant fees. How much of clearance fees do artists actually see, and how much of those go to the holding companies?

logical?

Aufderheide makes the point that the idea of copyright clearance is at is base a logical system, but I definetly think that there has been a steady progression in the way the system is enforced that strips it of its logic. She also makes the point that this dillemma sparks dangerous self-censorship. This is especially true. As someone who plans on being a film director, I am influenced by directors like Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, Oliver Stone and Paul Thomas Anderson who consistently use popular music in their films. I myself plan on doing the same in my own films someday, and the thought of not being able to do so really bothers me. I can understand how those dealing with the same dillemma can develop a defeatist attitude towards their work, and that is what is most dangerous about this whole situation. The copyright clearance rules in place today are a form of censorship that will be a detriment to the creativity of the arts if it keeps progressing in the same direction.

Copyright: A negotiated tension

In today’s culture filled with access to digital formats of texts, music, photos, and film it has become increasingly easy to acquire such material, but as litigation continues, increasingly more difficult to produce anything out of previous work. The documentary film-maker weaver of multiple texts, interjecting intertextualality into cohesive arguments and ideologies is hampered by the inability of others to understand that the documentary more often than not is a variable collage of other’s work. When addressing a particular issue or time period it is necessary to reference and intertwine previous representations of that subject or history. To limit the documentary film-maker to a hodgepodge of filler material, scrapping the bottom of the barrel for the sake of production costs is a shame. Many new ideas and truly visionary takes on the world we live in might be lost if the current trend does not change.

What’s Mine Is Mine…And Not Yours

After reading Patricia Aufderheide’s article, I found it very interesting when she pointed out that, in this ‘battle’ over having to pay copyright fees, people are having to fight for our “right to quote and comment on our own culture.” Sure, I accept that people want to get paid for others using their stuff, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of the public’s interests. Aufderheide mentions that “‘fair use’ is guided by one general concept: Do the public cultural benefits of the use outweigh the private economic costs?” Obviously, the public cultural benefits rarely outweigh private economic costs. Because of this, such strong copyright laws can greatly hinder a public’s right be informed, and in this case, to be informed through documentary films. Because of the ‘copyright stronghold,’ documentaries are having to avoid critical points of view that come through, as Aufderheide mentions, “social criticism, cultural commentary, historical films, satire and parody.” Documentaries are there to inform people about events and issues that have occurred or are occurring in our lives, and to put such great restriction on the people who provide this information can be detrimental to the progression and awareness of our society.

Is it really necessary?

I think this article was very interesting although it failed in looking at things from both sides. Aufderheide makes a great point in illustrating how now days you need to be extremely careful of the licensing you are required to acquire when it comes to anything related to a copyright violation. However, I feel divided in this issue; I understand artist should be paid for the use of their music, or anything of that sort, however to have to pay ridiculous amounts for the use of one lousy song in the background of something? That music use should be negotiated between the artist and the filmmaker.

Oh come on, lets be logical

The laws behind copyrighting are essential logical; counterbalance the worker for his work. A songwriter can only charge so much for the showing of his talents. Therefore, anywhere he can scramble for extra sources of income is fair. This idea is part of the drawbacks of living in a capitalist society. We are a group of people driven by the assumption that we will be compensated for our contribution to society. The question for society is how good of a contribution is popular culture, songs, and sayings. Can people base this claim on how music changes a person’s life? Sometimes after hearing a great song like Bob Dylan’s “Crazy Love,” I feel that the way I see life alters a little. But just because I just made a reference to the powerful performance, does not mean I have to pay Robert 10 cents. In my personal opinion, when a song is placed on a soundtrack, a movie, or in a broadcast, the song’s usage should be accredited to the song writer or owner of the rights. Along with written credit, a small but adequate pension should be awarded. However, it should be a set rate to ensure fairness. Wham’s “Wake me up before you go, go” may not be as epic as a Vivaldi movement, but it is still an original work that no other person should profit from.In the same point of reference, I do not agree with companies or private investors buying the rights to other artists’ work. Where does Warner Brothers get the right to purchase a phrase such as “Happy Birthday” that is used everyday by everyone in the world. There is a line to be drawn when the origin of the phrase cannot even be placed. Therefore, popular culture should be open to all for its basic definition, popular society’s influence on its’ culture. In the case of dead artists, it is up to the benefactor of the will to determine whether the song or lyric should be compensated. In other words, music by Elvis should go to his family or an organization, not to a studio trying to make extra money through random investments.

Who needs copyrighted material anyway?

Copyright interpretation has become a paramount issue for artists dealing with any media, but has become especially important for filmmakers. Producers of copyrighted material are certainly entitled to royalties for their products, but I do not believe it is fair to charge someone ludicrously high royalty fees for a song that is inadvertently playing in the background of a film. Had a conscious effort to include copyrighted material been made, then I believe that filmmaker has an obligation to pay royalties to the owner of the copyrighted material. The ability to determine if a song or another cultural reference was incorporated intentionally may be difficult, but with a film such as Tarnation it seems clear that Caouette unintentionally recorded popular music in the background while filming his family.

As a student filmmaker I quickly learned that using copyrighted material in my films is not feasible. There is a desire to include music that seems relevant to the film, or that the filmmaker personally enjoys, but the meager budget of most college filmmakers would likely not be enough to include even one copyrighted song. Luckily, I found a great solution to the problem of finding music for films.

There are many college students who are also musicians. Whether these musicians are in a band, trying to establish one, or just playing for fun there is often a willingness to produce music free of charge for student films. The benefits of this relationship are reciprocal, benefiting the filmmaker and musician. The filmmaker has an outlet to share new music with an audience who otherwise might not have heard it, as well as free music for the film. The musician is given free exposure for their bands thereby increasing their potential audience. This not only creates an awareness of the music, but also associates it with a film, which can often make music more memorable due to the visual material it has been incorporated with.

So any student filmmakers out there in need of music should turn first to their peers. Dealing with the legalities and royalties of copyrights will be a financially draining and time consuming experience. Having a friend or classmate create original music for a film, or allowing you to use songs they have already written, results in a further synthesis of creativity than the film itself would allow. This mutually beneficial relationship established early on can spawn further creative collaborative efforts which could last far beyond the college experience.

Copyright laws need updating

I think any discussion of self-censorship is logical, but why does it have to be self-censorship? I think the direction copyright protection has been taken is flat out censorship. If a filmmaker has used an image or sound but then discovers he/she does not have the money to pay for it, they will be forced to take it out. In my opinion, this is highly disturbing in a free society, especially one that places unique importance on free artistic expression. The last post makes the point that we should simply opt not to use media which has been used elsewhere and instead create our own, but this completely destroys the notion of art building on other art. In a so called “intertextual world”, everyone should be able to freely use any form of media to express exactly what they want to say. Does this mean that the poor person can’t use the same song that a rich person can use in his/her film to make the ending more effective? Now, I am not advocating wildly using other people’s work without giving them recognition. Ironically however, it seems that the capitalistic society that spawned Hollywood and new forms of art is seemingly turning its greedy back in frantically protecting everything it creates. Such a society only stifles innovation and financially restricts artists. However, such laws were made originally with good intention, and are simply vastly outdated and in need of revision. For example, the rampant file sharing phenomenon (which has stemmed to illegal downloading of movies) proves that the digital information age has caught up to copyright law and it is no longer effective on many fronts. Corporations have succumbed to desperately trying to sue anyone who it deems a major violator, but this completely neglects the nature of digital media and the way it spreads. As new forms of media appear and artists and corporations attempt to massively stamp copyrights and trademarks on every new form of image or sound, the progression of any “postmodern” atmosphere will be destroyed. I believe copyright law will eventually change as time progresses simply due to its lack of efficacy and common sense.

Who are we protecting?

I agree with Aufderheide first off in that I think it is pretty ridiculous that there is no a central database of who owns what in the copyright world and I believe that is a problem that should be properly addressed. There is really no reason why this is still a problem in this day and age. We live in a time dedicated to collecting and organizing information. Someone needs to get on the ball.

I also agree with Aufderheide in that some copyright laws should be revised. First off there should be more strict laws on what belongs to the public. I am not up on the facts of this but I don’t think some cave man gets a dollar for every wheel being used in the world. In that spirit I think that after a period of time artistic works should become part of the public domain. When something is so old that it is part of our collective culture I believe that all people should be able to use it and comment on it. Aufderheide’s example of having to pay for the copyright fees of God Bless America is a perfect reflection of this idea. I mean let’s be realistic the composer has been dead many years, what Artist are we protecting with this copyright law.

Fair Abuse? Hardly. These people are perfectly within their bounds.

Copyright laws are in place to assure that creative works will be produced for the good of the public by providing the creator with an economic incentive to produce original works. They were originally designed to protect against censorship, but now they are almost synonymous with the word. As the article says, what was once assuring creation is now suppressing it. It seems like more and more I’m hearing about artists being confronted by lawsuits or huge legal fees in dealing with fair use of others’ copyrighted material. Be it documentaries, indie films, or hip hop, modern art is being full on assaulted by copyright laws. The federal courts are going to need to mount a decision that allows for the continued use of others’ work without enormous fees or the futures of certain art forms are at risk. Without permission, it is illegal to use someone else’s work within your own even for nonprofit ventures. Something has got to change, and fast, or copyright laws may end up destroying the incentive they are supposed to be promoting.