A Column About Columns

by: Horace Newcomb / University of Georgia

In the spring of 1973, I had begun my second semester teaching in the American Studies Department at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County. Unlike many American Studies programs, the department (there were only five of us) was self-contained and not based on joint appointments. I had been hired the previous spring to develop courses in the study of popular culture as well as to offer seminar courses on topics of my choice. It was a grand appointment. The first Popular Culture Association meetings had been held just three years previously. My colleagues taught courses in Women’s Studies issues, Community Studies, and other rich areas that allowed us all to read across history, literature, sociology, anthropology and other disciplines and fields. All were firmly committed to the study of popular literature, film – and even television.

Each of us taught three courses every semester to bright undergraduate students. Many of them were first generation college students. Most lived at home with their families. Both these factors matched my own experience and I was pleased to be there, to discover what a fine city Baltimore was and is and what a fine university was and is UMBC.

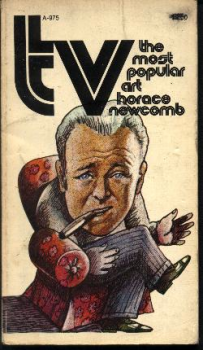

TV: The Most Popular Art by Horace Newcomb

I also had a book contract with Doubleday/Anchor for the project that became TV: The Most Popular Art. It was going somewhat slowly given that I had moved from one institution to another shortly after receiving the contract, made that move with two small children, helped Sara Newcomb situate our family in the new setting, and prepared new courses. Still, I had interests in possibly working in some aspect of the television industry and made time to arrange a visit to the General Manager of the Maryland Public Broadcasting Station, whose name I have forgotten. In our meeting I explained that I took television seriously and was writing a book about popular, fictional television. He mentioned that Judy Bachrach, the television critic for the Baltimore Morning Sun (there were still two papers in the city, the other being the Evening Sun), had recently left that post. He suggested I speak with the features editor about writing for them in some capacity.

Charlie Flowers, features editor at the Sun, was a Tennessean, a Sewanee graduate. We hit it off. I regaled him with stories about facing the Sewanee debate team as an undergraduate at a small liberal arts college in Mississippi, remarking on the fact that their team wore academic robes, in the manner of exclusive British colleges, and would swoop into dreary classrooms on the southern debate circuit, briefcases in hand, robes flowing sufficiently to intimidate any opponent. Charlie opened the possibility of writing the television column and asked that I submit a sample piece. That night I wrote a 600 word review of The Waltons, which had just begun its run on ABC. He then asked for another. I’m not sure what I wrote for the second. He called a few days later and offered me the job.

Cast of The Waltons

For the next fourteen months, while teaching full time, I wrote 600 words a day, five days a week, for $35 a column. At the end of that run I was fired or quit, depending on the story, largely because as a freelance writer I had replaced a member of the guild that represented writers at the paper. The guild had finally noticed the television column and complained. I was also very tired of trying to fill the space.

There were no VCRs in those days, no email, no preview copies unless one went to the local affiliate and viewed a closed-circuit broadcast feed, an event rare enough in itself and almost never in line with my schedule. My practice was to view a television show, go to the basement office, type a review or comment, then drive the copy to the paper before the 10:30 deadline. I had persuaded Charlie to allow me to “review” shows that aired two or three nights earlier in some cases. I had also informed him that the column would be about television content, that I was not a “media reporter,” that I would not comment on details of “the business,” or cover FCC hearings in Washington. This was to be a column of television criticism.

This, too, was a grand arrangement. I wrote a terrific column (if I say so myself), on Elvis’s Hawaii Concert. I reviewed “The Execution of Private Slovik,” one of the best social problem dramas produced by Richard Levinson and William Link. I wrote a column complaining that baseball on television was terribly boring (as it was thirty years ago), and received my first letter from a reader. A thirteen-year-old girl informed me of my stupidity, of the delight she and her family took in watching games together, of the pleasure in seeing her team on the tube. It was not the last letter challenging my intellect, credentials, sanity, or authority. But neither were these “critics of the critic” the only correspondents. I often received praise and thanks for taking the medium seriously.

And this was my intent. I wanted to provoke talk and thought about the medium, to show that it could be taken seriously. During the Watergate hearings I wrote commentary about politics, filtered through comments about the television personae and performances of senators, presidential aides, burglars and journalists. When I wrote about visual technique, I tried to think about shows that had aired long ago to demonstrate developments in the medium. During this period I offered my first course in the study of television. To do so I scheduled the course at night, rolled a cart with TV set into the classroom, viewed a show on the air and discussed it with students. Later, I used a version of the first Sony half-inch, reel-to-reel videotape recorder to take some shows off the air for later presentation and discussion. As I wrote chapters for the book, my approach fed into the column. As I wrote columns about current television, the ideas fed into the book. My hope was that it, too, might be more widely read and lead to discussions in other arenas, perhaps even among industry professionals.

That did not happen. Instead, the book was read in English departments, American Studies classes, and fairly quickly in various sorts of “communication” departments, even in some programs focused on “cinema.” As a result, most of the rest of my academic career was redirected.

But the column writing remains a touchstone for me and I’m grateful for another opportunity, in Flow, to comment occasionally on the more public aspects of television. It’s not the same, of course. The excitement of writing my 600 words knowing they would be read by several thousand people the very next morning is hardly matched, even by the reach of the internet, when I recognize that this new audience is already so predetermined. As David Thorburn and I have often discussed, we still have no good, strong, public vehicle for television commentary. Newspaper criticism has, to be sure, improved dramatically in recent years. Shales’ curmudgeonly voice continues to mark a standard, and his colleagues at the Washington Post, numerous writers at The New York Times, and some of the news magazine writers all add to a richer, more thoughtful discourse surrounding this strange box. I hope other generations of informed writers will take up places at other venues. I hope they will lead to columns that might be collected into collections of columns, applied in better, more meaningful ways. It’s a great medium, a great site of expressive culture. It still deserves better than it gets.

Links of Interest:

4. TV.com: The Guide to the Television Shows You Love

5. PopMatters, Television Review Archive

Image Credits:

1. TV: The Most Popular Art Cover

Please feel free to comment.

technology and writing about TV….

What strikes me most here is Newcomb’s discussion of the technological difficulties of studying and writing about television in the not-so distant past. I am truly a brat of a new era because I complain about having to write about television texts that I can “only” find on VHS… The other point I want to address here is the allusion Dr. Newcomb makes to the divide between “scholarly” television analysis and mainstream television criticism, like the column he wrote for the Baltimore Sun. How can we make sense of this in terms of television studies’ current “rising stock” in the academy (assuming, of course, that this stock is rising)? Is it important that such a conceptual divide be maintained? Or do television scholars have an interest in recognizing where the goals of these two pursuits intersect?

writing about TV

Newcomb’s description of the technology available to one teaching a class on television could not be more different from my own, who had the use of an “A/V module” equipped with a VCR and a DVD player. But what strikes me about his column is a sentiment with which I am entirely sympathetic: that in the popular press, television still receives little thoughtful criticism. While we in the academy are breaking down the boundaries between “high” culture and “low,” insisting that they are merely social constructions, it seems outside of the academy this binary still holds weight; that despite years of serious study, television is still lacking the credentials of a vibrant cultural form long ago afforded to film.

Who’s watching?

A couple of thoughts: First, I wonder who Newcomb refers to when he talks about the “predetermined” audience for FLOW? It seems that an online forum does have the potential to reach outside of this “predetermined” group, but that that is an issue that the editors must actively address. How do we do that? How do we acheive the kind of public participation that Newcomb so appreciated while working for the newspaper?

Second, I suspect that TV’s currency might be rising outside the academy as well. I still run into people who dismiss TV as “brain rot,” but it seems to me that shows like The West Wing that star major film actors are becoming more common. There is no longer a one way flow from TV to movies for actors, but more flow back and forth. Is this wishful thinking?

Pingback: FlowTV » Speaking to Each Other at Last? The Ghost of TV Past, Present and To Come…