Little Mosque on the Prairie: The Life and Times of the CBC

by: Michele Byers / Saint Mary’s University

In November, I attended a small conference for emerging scholars working in the area of Canadian media policy hosted by the Beaverbrook Fund for Media@McGill at McGill University in Montreal. Among the presenters there was at least one former employee of the CBC–the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation–the nation's public broadcaster. Canada has quite a different history of television broadcasting than does the United States. The public broadcaster was long preeminent, and its mandate has been to show the nation to itself (and to prevent the further encroachment of American Imperialism via television–yes we were worrying about that even when television was young) and in so doing to “better” the nation. With a vast landscape, and relatively sparse populations who are often regionally or extra-nationally-identified, this was (and remains) no easy feat.

The question on the table for a number of presenters was: should we be funding the CBC when it clearly isn't doing its job? This was coupled with another question: should Canadian broadcasters continue to be forced to air a certain percentage of Canadian programming (via CANCON laws), as it's far cheaper to buy American programming than to produce Canadian programming. The argument has been made that without the government “safety net,” Canadian television might disappear altogether (Grant and Wood). These questions are related to issues somewhat larger in scope: the mandate of the CBC to show us the nation as a whole, that is, all regions and the diversity of cultural populations within them, and the CRTC–Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission–regulations within the Broadcasting Act that lay out in several places the rules about representing the diversity of the nation, even as the Act strives at the same time to lay out a nationalist project. This is, specifically, a mandate of both the Corporation and other, including private, broadcasters.

As Serra Tinic points out, cutbacks at the CBC have long meant that the Corporation has become centralized (that means Toronto-ized) and the regions have all but lost their local offices and often their access to programming on the public broadcaster. Conference participants pointed out that some of the recent attempts by the CBC to garner high ratings (not part of its mandate) have been embarrassing disasters. The most public of these was the CBC's attempt to make up for passing on the wildly successful Canadian Idol (which, to some degree, meets the broadcaster's regional and national mandates) with another reality TV series called The One. The decision to air an American reality series (even one hosted by CBC regular George Stroumboulopoulos) during a timeslot that, in some regions, belonged to a national news program (The National with Peter Mansbridge) did not inspire confidence in many viewers. The fact that the show failed miserably in both Canada and the US sealed the deal. People were thinking: “this is what we are paying to maintain a national broadcaster for? I don't think so…”

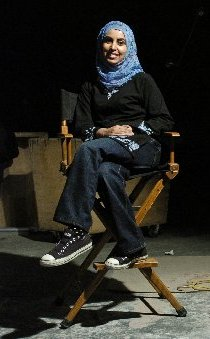

So we might look at Little Mosque on the Prairie as the CBC's attempt to redeem itself and to get back a bit of the national audience (as well as to garner some international cache, which it has). The sitcom takes as its premise the arrival of a handsome young Imam from Toronto (a former corporate lawyer) to a tiny Muslim community in a small prairie town. The show is, in a sense, as much a gentle critique of urban cosmopolitanism by the inhabitants of the “hinterlands” as it is of the Islamophobia of the other residents of the small Saskatchewan town (Bodroughkozy).1 The new Imam's frustration about not being able to find a cappuccino is played for the same laughs as is the frustration he feels at being misunderstood by the non-Muslim townspeople, many of who assume he is a terrorist. The series is the creation of Zarqa Nawaz, a Muslim woman who has lived in the prairie city of Regina for the last decade. Nawaz's company, FUNdamentalist films is, she jokes, about “putting the fun back into fundamentalism.” The series title is, of course, a play on the immensely popular book and television series Little House on the Prairie, a narrative about colonial expansion and the hardship and joys of the American settler life. Why this was chosen as the title, in that the book is, in a sense, quintessentially American, is not clear. But it may be that “mosque” is disruptive of the myth of white settlement that is part of the historical narrative of both nations.

Before it even aired, Little Mosque delivered a lot of attention to the CBC. Some lauded the broadcaster for bravely addressing an issue, and with humour, that most people wouldn't touch with a ten-foot pole (the more hidden suggestion that they were brave because of the danger they might face from “extremists” and the Islamophobism of that suggestion has not been much discussed). Others felt that this wasn't the proper venue, or tone, for addressing these issues. Either way, few people could remember the last time the CBC had made such a big splash in the international news (including the New York Times, CNN, and the BBC); Little Mosque has elicited interest from a number of television networks internationally, as well as American cable stations. At home the series found over 2 million viewers for its first episode, something that hasn't happened for the CBC in years (and which is considered an excellent percentage of the national viewing audience for any network).

The press coverage that appeared after the series' first episode aired likely reflects a broader split in opinion about the series: Margaret Wende who thought the show was “way too cute” and John Doyle who thought it was “gloriously Canadian” (both in the January 9th print issue of the Globe & Mail). For Wende, Little Mosque takes the easy road, tackling difficult and controversial issues with a feather duster: young, hip Imams, no in-group conflict, gentle racism, and so on. For Doyle, the series' “mere existence is a grand-slam assertion that Canadian TV is different and that the best of Canadian TV amounts to a rejection of the hegemony of U.S. network TV” (R1). Muslim viewers whose views have been reported in the press have been similarly split between those who feel the series will help demystify Muslims to non-Muslim Canadian viewers, and those who are concerned that the series' vision of Muslim life will paint a reductionist picture for non-Muslim viewers; some have even gone so far as to call the series racist and bigoted.2

Having watched the first few episodes of Little Mosque, I find my own feelings fall somewhere between these positions; that is, in an ambiguous space I might call proud disappointment. Part of me has found the show disappointing in its simplicity; a simplicity that is often part of sitcom culture, but that is bypassed by many sitcoms. Everything on Little Mosque is as flat as the prairie landscape it's set in; its controversy is polite, its jokes are familiar, its characters relatively one-dimensional. At times I agree with the more strident critics who see the series as representing a narrow vision of Muslim identity and a vision of non-Muslim (rural) Canadians as ignorant bigots. But another part of me is pleased to see a series about Muslim life that breaks with the tradition of representing Muslims as secondary characters introduced to teach others about the perils of racism, or as terrorists (Shaun Majumder, for example, a star of the Canadian political satire This Hour Has 22 Minutes recently got his big US break, playing a terrorist on 24), or even as necessarily urban. The only other show that I can think of that has Muslims (plural) at its centre, is Showtime's incredibly problematic Sleeper Cell (airing on The Movie Network in Canada). I am proud that Little Mosque is being made in Canada; that it can be made in Canada; that there is room to fund such a vision which, while far from perfect, may help us laugh and learn at least a little.

That said, Little Mosque is just finding itself; if the series is popular perhaps it will spread its wings, take a few more risks. And maybe it will help demonstrate to the nation that the national public broadcaster has a continued role to play after all.

Notes

1 On the other hand, this might also be read as a critique of rural populations; the implication is that in more sophisticated urban spaces people would not be so racist.

2 Note that there is a very long history of debates about “good” and “bad” representations of various groups in television and that many scholars have pointed out that these terms don't help us much because they elide broader questions like, good or bad for whom, in what context, according to whom, and so on. While it is clearly necessary to mark and interrogate these tensions, recognizing their pervasiveness is also important (most recently, for example, in the criticism of The L Word for its narrow representation of lesbian characters).

Suggested Reading

Aniko Bodroghkozy, “As Canadian as Possible…: Anglo-Canadian Popular Culture and the American Other,” in Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, edited by Henry Jenkins, Tara McPherson, and Jane Shattuc (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003).

Peter S. Grant and Chris Wood, Blockbusters and Trade Wars: Popular Culture in a Globalized World (Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2004).

David Hogarth, Documentary Television in Canada: From National Public Service to Global Marketplace (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002).

Mary Jane Miller. Rewind and Search: Conversations with the Makers and Decision-Makers of CBC Television Drama. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996)

Paul Rutherford. When Television Was Young: Prime Time Canada, 1952-1967. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000)

Serra Tinic. On Location: Canada's Television Industry in a Global Market. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005).

Image Credits:

1. Scene from Little Mosque

2. Little House title screen

3. Little Mosque‘s creator, Zarqa Nawaz

Please feel free to comment.

Great piece!

This is the kind of work LOVE Flow for! Thank U Michele for a great article – informative, interesting and thought provoking. Sorry I don’t currently have the time to share any of these thoughts :) but I did want to praise the contribution!

nice to read about something Canadian

This is a great piece on Little Mosque! I haven’t had a chance to watch the show yet, but after some interesting discussions with students in class yesterday, it seems like a good idea to check it out. Based on the opinions of those who have seen it (we were discussing representations of race on TV), I would suggest that many of their responses fit into your ‘proud disappointment’ category. Personally, I feel that way about much TV programming! :) That being said, there are still strong sentiments regarding the ‘quality’ of Canadian TV underpinning most people’s critiques. We’ve heard it all before: Cdn. TV isn’t as ‘good’ or as stylized as US TV, therefore it’s better, more interesting, Cdn. actors aren’t real actors, etc, etc…but that’s a whole other discussion I suppose.

the sitcom problem

The Canadian ‘problem’ echoes around the world! Attempts at creating a New Zealand sitcom have, at best, been fitful asnd only partially successful. Australia has been more successful recently, with Kath and Kim (based on very broad caricatures of lower class, aspirant characters).The real problem is that the sitcom format is such a thoroughly American (and static?) genre, with a long history of exemplars–from I Love Lucy, to Seifeld and Ugly Betty (although that might be more of a dramedy. There is greater freedoms in hybrid genres, as in blending serial drama with stcom.

I hope we get to see Mosque in NZ (we have had Trailer Park Boys). There ought to be more here, given Canwest owns two of our FTA channels.

Great piece. Let me add one more thing. Surely an important driver in the CBC’s decision to buy, and perhaps the producers’ thinking behind what they put up for sale, was Corner Gas.

Corner Gas is one of the most successful Canadian sitcoms or comedy shows in history, and its setting is almost identical to Little Mosque’s — a small Saskatchewan town living in a bubble.

It goes further, too. Apparently the key writers behind Corner Gas are moving over to, or lending a hand with, Little Mosque. Stay tuned…

Pingback: FlowTV | A Place at the Table: Aliens in America and US policy in the ‘Islamic World’