Flotsam

by: Christopher Anderson / Indiana University

Suppose you’re starting a new electronic publication devoted to smart writing about television and emerging media. You might call this publication, Flow. A brilliant choice: succinct and evocative, familiar yet still fresh. It’s an ideal word for its purpose and yet it hasn’t exhausted the possibilities. Let’s imagine another publication about television. Let’s call this one, Flotsam.

While Flotsam is an alliterative title plucked from the same realm of watery metaphors as Flow, we must consider the differences: waters flow smoothly. Waters flow in the here and now (the flow is called a current, after all); because no human observer can perceive more than an instant of the waters’ swift passage, the flow’s past and future are at best dimly imagined when one gazes upon a current. Waters flow in a single direction-relentlessly forward. As a metaphor for the human experience of time, flow reminds us-as an ancient talk show host once observed-that we can’t step into the same river twice.

As a metaphor, flotsam — the pieces of a ship’s wreckage found floating on the water’s surface — suggests a different relationship to the passage of time. Flotsam disrupts the smooth surface of the present, hinting at calamities that occurred sometime in the past. Flotsam lies hidden in water’s depths, indifferent to its flow. It breaks loose and bobs unexpectedly and unpredictably to the surface as ruined fragments of something that once moved forward and once was whole. Flotsam is a testament to misfortune, a haunting reminder of the past in the here and now.

For those initiated into the cult of academic television studies, flow conjures up the pioneering work of Raymond Williams. His use of the term to describe American television in the 1970s survives as a fundamental concept in television studies. Even a casual reader can appreciate the richness of the metaphor: it invokes the physical flow of electrons that makes television possible; the calculated flow of television content from one program or commercial to another, and a distinctive way of experiencing a broadcast medium over which a viewer may exert little control.

As metaphor and critical concept, flow encourages us to see television from a perspective influenced by the meanings embedded in the word. Television is an abundant, steady stream that emanates from a source, occurs in the unfolding present, and moves, smoothly and readily, forward. In much of our critical writing, we construct precisely this image of television. Oddly, the television industry — which wants nothing more than for viewers and policymakers to focus on the Next Big Thing — also encourages this image of television in countless ways. Thinking of television in terms of flow may have descriptive value, but does it have any value as a critical concept if it simply recapitulates the strategies of self-promotion employed by the TV industry?

Television might look different in a publication titled Flotsam, where writers seek peculiar fragments of the past that bob unexpectedly to the surface of awareness, indifferent to television’s flow and contrary to the designs of the television industry.

Last Thursday evening a television viewer in Bloomington, Indiana may have floated comfortably along the flow of the top-rated CBS schedule, from Survivor to C.S.I. and every commercial in-between. But Friday morning’s newspaper brought a jolt from the past and an unexpected encounter with CBS. A judge in the U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the environmental group, Protect Our Woods, could move forward with a lawsuit originally filed against the Environmental Protection Agency and CBS in 2000 — five years and three appeals ago. The suit charges that the EPA and CBS have failed to clean up three hazardous-waste sites in Bloomington that have existed for decades.

Hold on a second! CBS is responsible for hazardous-waste sites in Bloomington? Could this be the fabled site where the network buried the remaining episodes of The Will (recently cancelled after a single episode!)? No, these are three of six landfills where the electrical manufacturer, Westinghouse, dumped electrical capacitors containing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from the 1950s through the 1970s. These chemicals, which are suspected of causing cancer and other chronic diseases, have leached into the soil, the groundwater, and nearby streams. The developers of a new Bloomington subdivision have complained that PCBs continue to leak from unexcavated limestone deposits, where they have been carried in the groundwater.

Westinghouse is long gone from Bloomington, but the PCBs linger — even after two decades of remediation. CBS inherited the legal liability for this toxic mess following its merger with Westinghouse in 1997. The liability was then passed along to Viacom with the merger of 1999. It’s a scenario out of science fiction, but a reality of the conglomerate era: the #1 television network in America is responsible for a legacy of deadly hazardous waste in a lovely Midwestern community, where the title Survivor strikes a little close to home.

You’d have to be a real killjoy to remind people that someone has manufactured all of those HDTV sets and digital video recorders at Best Buy, that some people and some communities bear the real costs of technological progress. But in the communities where this technology has been manufactured — if not the landfills where you dispose of your obsolete equipment — the past can bubble to the surface after a good hard rain causes groundwater levels to rise.

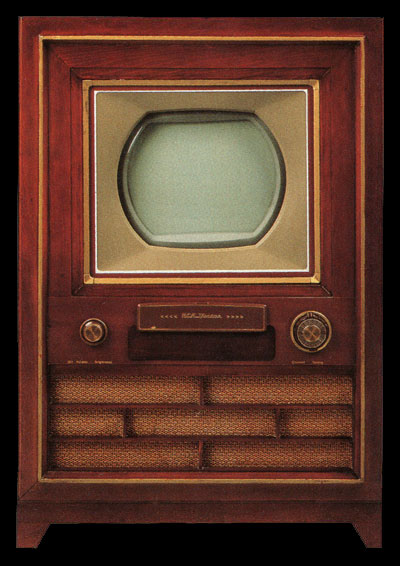

The first mass-produced color television set in America was manufactured at the RCA plant in Bloomington in March 1954; and the community still wears the accomplishment with pride (although the abandoned RCA factory was demolished and carted away in dump trucks several years ago). Soon Bloomington became a small, but significant, manufacturing center for the electrical and electronics industries, as General Electric and Westinghouse constructed plants of their own. The postwar economic boom in America — not to mention the television revolution — would not have happened without the electrical capacitors manufactured at Westinghouse. By the late 1970s, however, some long-time employees at the Westinghouse plant had registered the highest PCB levels ever measured in human beings.

All of this sounds like the premise for a promising crossover episode of the CBS series, C.S.I. and Cold Case. A man died of mysterious ailments in 1979, but only the crafty and dogged investigators at present-day CBS, armed with sophisticated modern technologies, can bring his children some comfort by determining what caused his death. The only problem with this scenario is that, in the real world of corporate law, a company like Viacom ensures that the legal process drags along at a pace that can’t possibly be condensed to suit the time-scale or narrative structure of a procedural drama. This most recent lawsuit was filed in 2000 and the plaintiffs, exhibiting remarkable endurance, have only just received approval to take the case to court. The experience of time encouraged by television’s flow cannot prepare us for the glacial crawl of a corporate liability case. These cases disappear from public awareness and they reappear unexpectedly years later, reminding us, if only briefly, that television is more than the flow of programming.

General Electric, the parent company of NBC, did not use PCBs in its Bloomington plant; but it has dumped thousands of tons of the toxic chemicals into the Hudson River north of New York City. In its most recent appeal, GE has challenged the EPA’s legitimacy in designating Superfund cleanup sites (and was represented in court by the stalwart liberal attorney, Laurence Tribe). Thanks to procedural delays, it will be years before the case is finally decided and the cleanup begins in earnest (even as GE advertises its new water purification technologies in television commercials!). Meanwhile the Hudson River flows, and NBC programming flows, but the PCBs remain, still lining the riverbanks, inert and deadly, indifferent to the flow, a threat to return one day as flotsam.

Image Credits:

1. Flotsam

2. RCA’s first color TV set

Links

Article on Federal appeals court ruling from Indianapolis Star

Protect Our Woods homepage

CBS homepage

Columbia Journalism Review’s corporate timeline of Viacom

ATDSR FAQs regarding PCBs

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Week on Flow (April 15, 2005)

The term “Flotsam” also describes more accurately than “Flow” the way in which television attempts to present itself: a series of separate events. Television programming brackets the so-called televisual “flow” into discrete units, individual items that can be accepted or rejected. In this way, it creates a sense of product differentiation. More importantly, this compartmentalization sets programs against commercials. Comparing televisual discourse to “Flow” obscures this aim. Using the term “Flotsam” helps to reveal television’s pursuit to create a sense of coherence and importance out of the stagnant pool of wreckage that we like to call information.