Infernal Archive: Medial States of Matter in the Netherlands Institue for Sound and Vision

Shannon Mattern / The New School

What happens when you mix this –

with this?

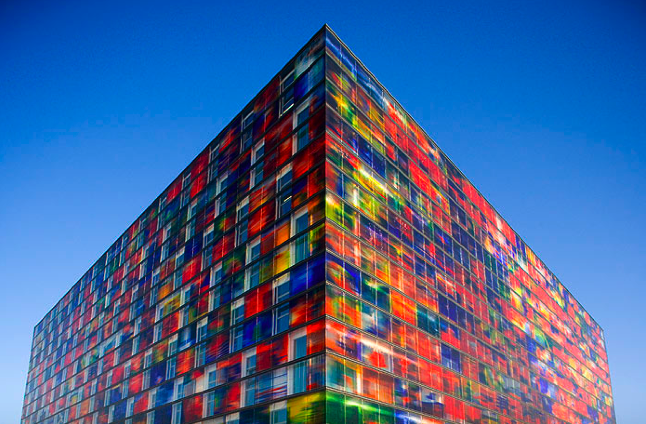

Well, in 2006, Hilversum, the media center of the Netherlands, got this:

It’s Neutelings Reidijk Architects’ Institute for Sound and Vision, a private audio-visual archive (one of the largest in Europe) serving national and international media producers and researchers, combined with a museum of Dutch media history – all inside one multicolored glass box. It’s an archive for the “motion graphics” age. At least that’s the story told by the building’s façade. A closer inspection of the building’s skin and a tour of the interior, however, reveal that this is an institution unsure of the archive’s position in the cultural landscape and its relationship to place, and uncertain about the status of the audio-visual in an increasingly digital media landscape.

Now, about that façade: Drupsteen entered the Institute’s archives to find a collection of recognizable images from Dutch media history; from those images he then cast molds, and into those molds he poured liquid glass. The result: shallow relief panels displaying, in smudged colors, “canonical television images etched in the national collective memory.” 1

From archival digital file to sculptural mold to cast-glass television screen. This cross-format media transfer created an architectural medium that “read” differently to different critics. New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff drew a parallel to print, describing panels “imprinted with the faint traces of shared memories.”2 In a switch, he then suggested that the “blur of images conveys the daily bombardment from the Internet, television, movies and newspapers” – yet here, on/in these walls, that media flow is “frozen in time, as if temporarily tamed.” The designers, meanwhile, hoped that the façade, viewed from a distance, would have “the aura of a flickering TV set in a typical Dutch living room.”3 The flicker, produced by a low refresh rate in a cathode ray tube set, seems an odd source of “aura” for a 21st-century institution – particularly one that would rather disassociate itself from flickers, frozen images, and other technical glitches.

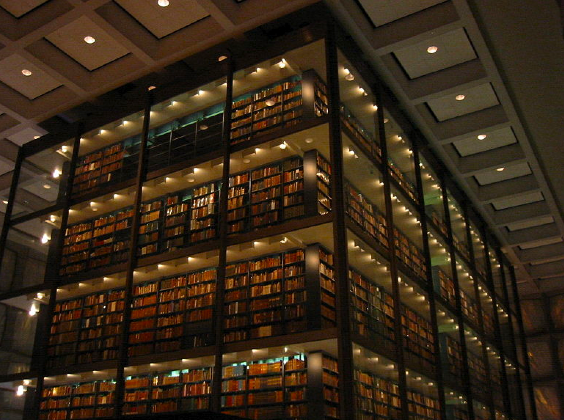

The designers then draw yet another seemingly paradoxical media-historical reference: “What we sought to achieve [with the façade] was the quality of light-transmitting cathedral windows, not just a piece of glazed…technology but a lightly tactile surface.”4 They aren’t the first to make such a comparison: as McLuhan explained, both the television and the stained glass window (and, we might add, the translucent marble walls at Beinecke) are “light through” rather than “light on” media; they’re both backlit – and backlit media, as McLuhan’s son, Eric, attempted to demonstrate through experiments at Fordham University in the late 60s, generate a heightened sense of tactility.5 It is significant that the only clarity or fidelity on the Institute’s façade emerges through its texture – in the relief. Through the panels’ chromatic blur we can still discern some tactile figural outlines: over there, an image of the Dutch queen on a bike; here, a favorite football star. Furthermore, this proposed phenomenological link between the television screen and the stained glass window suggests a similar connection between this 21st-century TV-cathedral-archive to its medieval, and perhaps even ancient, predecessors. Even in this progressive institution, the history of media, and the history of the archive, can’t help but rise up in relief.

Inside we find other blended historical references and more mixtures of the material and immaterial. The architects describe the interior as a “trapezium, a zigurrat and a rectangle that fit together like a puzzle.”6 These ancient forms are presumably a reference to the archive’s ancient beginnings. Yet the central hall is very much a heterotopia: it is flanked on one side by glass-enclosed offices, on the other by a stepped aluminum-paneled wall, and ringed by the iridescent TV-screen windows. Unlike at Beinecke, where the books reside at the volume’s center, we have here a void in the middle. This “canyon” is clad with natural slate; even the seating seems to be made of stone piles that rise up out of the floor. Ouroussoff likens the space to a necropolis – one that just happens to have a modern café with fluorescent orange upholstery, and sightlines to ubiquitous television screens. Upstairs, one might catch a glimpse of the theaters or offices or hear the din emanating from the interactive museum.

The Institute’s ground floor is at the middle of the building; “the public enters the Chinese puzzle at its center,” the architects explain, “with a…gigantic hovering block above their heads” and a “vertiginous crater beneath their feet.”7 That subterranean crater, glowing red, holds the archives: five underground floors containing over 700,000 hours of television, radio, documentaries, amateur film, and music, and more than two million photos from Dutch audiovisual history. Despite the cool undergrounds temperatures, the slate appears to melt into magma. Down there, in this “infernal” space (the architects use this term, although, presumably, without the diabolical connotations), the archival material exists in a similarly liminal state of matter: both physical and digital.

The archives are committed to ensuring the preservation of their material media; the sheer volume of the archival space (made all the more apparent by the depth of the archival crater one passes upon entering the building) indicates that its material holdings are extensive. At the same time, the Institute is involved in a massive Dutch government-supported digitization initiative, the “Images for the Future” program.8 And as indicated on the Institute’s website, it is deeply engaged in international “collaboration on developing metadata standards, the creation of universally accessible digital libraries, effectively dealing with evolving search and retrieval issues and solutions for long term preservation of audiovisual programme content and materials.”9 While these digital archiving programs have significant equipment and spatial demands of their own, the “state of matter” of the collection being archived – undergoing, like the glass relief panels on the building’s façade, a dramatic cross-platform transformation – is hard to pin down.

It is not clear here, as it is at Beinecke, what material lives at the center of this archive: what is the “stuff” of a Sound and Vision archive these days? Thus, the spaces for the collection are pushed underground and off to the periphery. To reach the archives, we have to dig down into a pool of magma, into that infernal crater, a place where states of matter–and media–are in flux.

Media archaeologist Wolfgang Ernst argues that the shift from the traditional text-based archive to the audio-visual archive represented nothing short of a new intellectual order, a “rupture of (an) epistemological dimension.”10 As many archives now make another shift–from the analogue audio-visual to the digital–the institution once again faces spatio-temporal and epistemological shifts. At the Institute of Sound and Vision, the archivists, while honoring their commitment to the Netherlands’ media past, seem also to be embracing the new archival order.

Yet the ground is literally moving beneath the archivists’ feet. The place of the archive is struggling to find its form. As performance scholar Diana Taylor explains, “place,” the archival “object,” and “archival practice” are inextricably intertwined:

An archive is simultaneously an authorized place, the physical or digital site housing collections; a thing or object, a collection of things, the historical records and unique or representative objects marked for inclusion; and a practice: the logic of selection, organization, access, and preservation over time that deems certain objects archiveable.11

Changes to any one of these elements require recalibration of the others. Now, anxieties over digital technologies, she says, often engender “nostalgia for embodiment.” We see the latter in the Institute’s seeming compulsion to convey–through its mash-up of historical architectural forms (from Beinecke to the cathedral to the ziggurat), its allusions to historical media and traditional building crafts, its abundance of heavy materiality–the institution’s continued commitment to the traditional values of the archive. Mix that with the ubiquitous television screens, the fluorescent orange accents, and the hyperactive media history museum and we get a confused, heterotopic institution, half above- and half below-ground, in-between medial states, filling up with magma.

Image Credits:

1. Gordon Bunshaft’s iconic 1963 Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

2. Designer Jaap Drupsteen’s stage show for “Monomanic Crush”

3. The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision (Photo by Iwan Baan)

4. Detail of the Institute for Sound and Vision Facade (Photo from Jaap Drupsteen)

5. Institute Interior (Photo by Iwan Baan)

6. Beinecke Library Interior

7. Institute Interior (Photo by Iwan Baan)

Please feel free to comment.

- Willem Jan Neutelings, Michiel Riedjik, At Work: Neutelings Riedijk Architects (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2005): 94. [↩]

- Nicolai Ouroussoff, “Heaven, Hell and Purgatory Encased in Glass” New York Times (May 26, 2007): italics mine. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Quoted in Uta Caspary, “Digital Media as Ornament in Contemporary Architecture Facades: Its Historical Dimension” In Scott McQuire, Meredith Martin and Sabine Niederer, Eds., Urban Screens Reader Institute of Network Cultures Reader #5 (Creative Commons): 67. [↩]

- Eric McLuhan, “The Fordham Experiment” Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association 1 (2000): 23-27. [↩]

- Neutelings & Riedjik: 64. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Peter B. Kaufman, “Video, Education, and Open Content: Notes Toward a New Research and Action Agenda” First Monday 12:4 (April 2, 2007); “Images for the Future” [↩]

- Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, “Organization” [↩]

- Wolfgang Ernst, “Order by Fluctuation? Classical Archives and Their Audio-Visual Counterparts” Archives Aesthetic Practices Seminar, National Library of Sweden, Stockholm, Sweden, May 19, 2009. [↩]

- Diana Taylor, “The Digital as Anti-Archive?” “Animating Archives: Making New Media Matter” Conference, Brown University, Providence, RI, December 3, 2009. [↩]

Pingback: MEDIAGRAPHY – THE LITERATURE REVIEW | Space Telling

Pingback: Word in Space | Space Telling

Pingback: Dutch Institute of Sound - Well Done Stuff

Great delivery. Great arguments. Keep up the good work.

Pingback: Archival Aesthetics (ft. Rigor + Taste) @ Princeton-Weimar Summer School – Words in Space