Project Dhee: Withstanding Heteropatriarchy and Queer-bashing in Bangladesh through Enclave Deshi Queer Activism

MOHAMMED MIZANUR RASHID / The University of Texas at Dallas

Sexually diverse individuals and communities are extremely marginalized and oppressed by the heteropatriarchal sociopolitical institutions and publics in Bangladesh, and South Asia more broadly (Karim 2014; Khubchandani 2016; Hossain 2019). The interface of colonial legacies and dominant religious ideologies have enmeshed non-normative sexual identities and practices in Bangladesh with cultures of the West, totally ignoring the histories of queerness in South Asia. The socio-cultural, gendered, and sexual lives of the Bangladeshi people are dictated primarily by two oppressive institutions – first, the constitution and legislation that has not been updated since the colonial era even after undergoing independence twice, and second, the dominant interpretations of the state religion of Islam that is strongly committed to compulsory heteronormativity, patriarchy, and cissexism. In May 2017, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), a special division of law enforcing agency in Bangladesh, arrested 28 men under suspicion of being homosexual. The arrest, made in Keraniganj, soon became a national phenomenon as these young men, aged between 20 to 25 years, were presented in front of the public through national television (Khokon 2017). Public discourse around the arrests mostly represented the dominant religious beliefs and heteropatriarchal ideologies that interprets homosexuality as sin and abnormality, and as I have argued elsewhere, the initial Bangladeshi queer rights activism that began in 2014 following patterns of Western LGBTQ+ movements, such as rainbow themed Pride rallies and public coming out parades, also played vital roles in buttressing this problematic assumption (Rashid 2022).

However, for sexually diverse and marginalized communities to challenge and carve out a space to realize non-normative sexual desires and to negotiate the politics of sexual identities within an extremely heterosexual place is not new in Bangladesh. As Shuchi Karim’s work shows, sexually diverse publics have been occupying both virtual and actual space, using them to communicate their sexual needs that is considered to be a crime by the colonial era legislature currently at work in Bangladesh (Karim 2014). Karim’s findings are not only important because it explores the entanglements between the private and the public and the ambiguous nature of sexual desires and identities within Bangladeshi gay and lesbian cultures, but also because without making explicit, her work gestures towards the fact that even before the intervention of organized feminist institutions and LGBTQ+ rights groups, enclave media cultures and communicative practices, both within and outside LGBTQ+ communities, supported queer possibilities and potentialities in Bangladesh. The extreme oppressive treatment of LGBTQ+ publics that is now exacerbated after the 2014 public LGBTQ+ rights activism, require a reassessment of how queer activism may tactically continue without drawing visibility. Within two years of the first public LGBTQ+ pride rally in Bangladesh, several organizers of the movement were either killed by armed religious extremists or forced to flee the country in fear of death. Under such extreme circumstances, a more enclave approach is necessary. More recently, queer activism in Bangladesh is taking an interesting maker turn, supported by the work of feminist makerspaces and queer maker cultures that tactically mobilize popular media and cultural production to extend the work of LGBTQ+ activism discreetly and effectively.

In Lesbian Potentialty and Feminist Media in the 1970s, Rox Samer explores how feminist cultural productions such as cinema and science fiction literature in the 1970s facilitated new formations of counter-publics and alternative interpretations around the meaning of lesbian existence. According to Samer, this work was taken up by fans and enthusiasts of particular media (Samer 2022). To reorient Bangladeshi LGBTQ+ activism from a hyper visible, and therefore potentially lethal, movement that prioritizes publicness and visibility, to a resistance that takes a more tactical and cultural approach to social transformation, the work of mobilizing such fandoms become crucial. In Bangladesh, the medium of comics and zines have long been a popular medium of entertainment and fandom. Contrary to perceptions around the recent rise of Western comics culture in Bangladesh, comics such as Vetal (1964), Nonte Phonte (1969), and Chacha Chaudhury (1971) have always been extremely popular in Bangladesh since their creation. The establishment of comic book imprints such as Indrajal, Diamond, and Raj, date back to the 1960s and have since been followed by immense fandoms. This popular medium is one of the avenues though which LGBTQ+ activism in Bangladesh is finding a way going forward in the midst of extreme persecution.

Dhee (2015) is a series of material comic strips, created by Boys of Bangladesh, an LGBTQ+ rights group based in Dhaka. The comic strip is presented as flashcards that tells the story and everyday experiences of a Bangladeshi lesbian girl named “Dhee” in the hopes of raising awareness around Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual identities and experiences in Bangladesh. Exploring Dhee from the perspective of feminist and queer makerspace activism is important, particularly because it lends itself to possibilities of approaching ‘Deshi’ Queer Activism from de-colonial and de-imperialized subjectivities. It also has the potential to respond to dominant narratives around Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual identities and practices being an import of the West, and situate them within Bangladeshi cultural historicities.

Dhee tells the story of a young lesbian girl from the suburbs of Dhaka city in Bangladesh. The narrative is told in first person by the protagonist Dhee and spans almost her entire life. Dhee, which was created in 14 months by four Bangladeshi queer content makers, is part of a larger project titled Project Dhee, a 5-year strategic plan to advance site-specific and fact-based knowledges around diverse sexualities often focusing on the multiple counter and alternate histories of Bengali non-normative sexual identities and practices that are almost never represented in popular media or public communication. Despite its popularity, Dhee resists being widely available to the public with its makers remaining largely anonymous due to the dangers they face. In an interview with German broadcasters Deutche Welle, one of the makers of Dhee who remained unnamed claimed that the flashcards were selectively made available to queer folks and allies in the hopes that they would share them further only to people they trusted. Additionally, the flashcards were made in a hidden queer makerspace where access to anyone except the makers was restricted for safety issues. It is important to note that the comics’ production and distribution, along with its makerspace practices implies a community of care where secrecy and safety is prioritized over visibility, publicity, and pro-active networking. This is necessarily a departure from the 2014 hyper-visible and public LGBTQ+ activism in Bangladesh.

The narrative and framing of Dhee is also worth analyzing. These are the opening lines of Dhee –

Ever since my childhood, I have always found myself oddly out of place. My mother was always scolding me, telling me to pay attention to domestic work, play with dolls or to keep my hair tied up all the time. But within my heart, I only wanted to roam around while letting my hair flow freely in the open air.

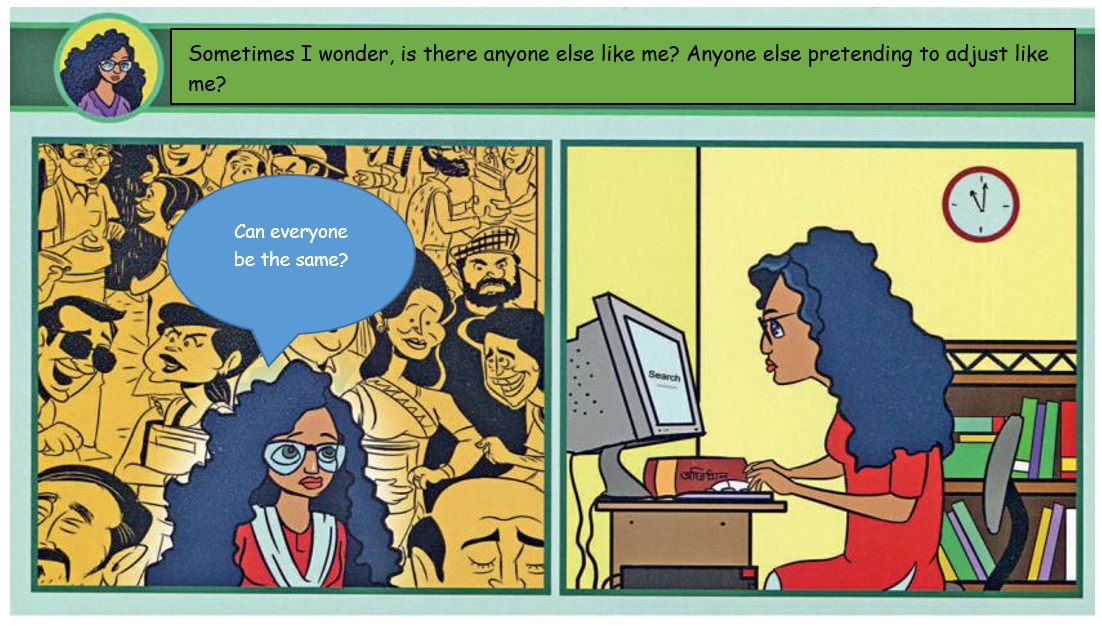

The very first page of the comic strip immediately draws our attention to Dhee’s childhood. Dhee narrates her story explaining how, for as long as she can remember, she has always felt out of place. Each of the graphic frames also depicts Dhee struggling to fulfill the gender roles society has imposed upon her. As the story progresses, Dhee becomes increasingly aware of her sexuality, and the misalignment of expectations around sexual desire, identity, and practice between herself and the dominant heteropatriarchal society becomes clear. Burdened by her desire and identity, Dhee tries to find answers and her probing leads her to uncover LGBTQ+ inclusive alternate historical references and contemporary community resources and support groups. As opposed to organizing pride rallies and drag events in Bangladesh, that is often understood as invitations to a primarily Western and otherwise unknown queer world from the outside, Dhee makes her readers familiar about gender and sexual diversity from within by providing access to the everyday oppressions, feelings and affects she experiences as a non-conforming Bangladeshi woman.

Project Dhee printed 4,000 copies of the comic strip and initially distributed them within close circles primarily through fundraising ceremonies and awareness building workshops. While mobilizing the popular medium of comics and using a culturally situated counter-history approach to challenge dominant gender and sexual norms in South Asia opens new avenues for the LGBTQ+ movement to forge ahead, it also raises concerns around how and when governmental and legal institutions may be forced towards more equitable policy changes. Perhaps the potential of Deshi queer activism and the possibility of an inclusive future that is less oppressive to the LGBTQ+ community of Bangladesh needs to negotiate between the sites of queerness, visibility, anonymity, publicness, decoloniality, and temporality. There is a lot to unpack, at least now, there are certain conditions in which the conversations may begin, and most importantly, continue without the fear of being hacked by a machete.

Image Credits:

- Cover page of the Dhee/ The Story of Dhee comics, 2015. From Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2015/sep/06/first-ever-bangladeshi-lesbian-comic-character-launched. Content has been deleted since 2016. (author’s collection)

- The Dhee comic strip flashcards. (courtesy of Boys of Bangladesh)

- Opening page of Dhee originally published in Bangla. (author’s collection)

- Dhee questioning Bengali normative social constructions. English translation. (author’s collection)

Hossain, Adnan. 2019. “Section 377, Same-sex Sexualities and the Struggle for Sexual Rights in Bangladesh.” Australian Journal of Asian Law 20(1): 1-11.

Karim, Suchi. 2014. “Erotic Desires and Practices in Cyberspace: Virtual Reality of the Non-Heterosexual Middle Class in Bangladesh.” Gender, Technology and Development 18(1): 53-76.

Khokon, Sahidul Hasan. 2017. “28 youngsters detained on charges of homosexuality in Bangladesh.” India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/28-youngsters-detained-homosexuality-bangladesh-978106-2017-05-19.

Khubchandani, Kareem. 2016. “LGBT Activism in South Asia.” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, edited by Nancy A. Naples, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss675.

Rashid, Mohammed Mizanur. 2022. “Queer Blogs and Digital Archives: A Tactical Shift Towards Queer Utopia in Bangladesh.” Media Fields Journal 17(1): 1-11.

Samer, Rox. 2022. Lesbian Potentiality and Feminist Media in the 1970s. Duke University Press.