Media Made Easy: Platforms and the Rise of Media-as-a-Service

Emily West / University of Massachusetts Amherst

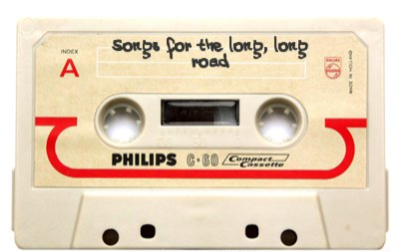

At the risk of projecting, people of a certain age may find themselves reflecting on how good we have it now, in terms of the convenience and access to an abundance of media we typically enjoy today. Surely no one born after 1995 can imagine staying up late to hear their favorite new song played on the radio in the Top 40 countdown, in order to make a poor recording on a blank cassette—the only way to reliably hear said song without getting to a record store and shelling out a hefty sum for the entire album. Or having to decide whether to make social plans or be home for Must See TV on Thursday nights, lest you miss out on a crucial event in Ross and Rachel’s will-they-or-won’t-they saga. Today’s media consumer, at least the consumer of means who can pay for subscriptions, does not contend with the scarcity or ephemerality of media in quite the same way. Advances in digital technology and computing—among them streaming, subscriptions, mobile devices, high-speed internet, recommendation algorithms, smart speakers, and the rise of the platforms providing them—have brought about an era of hyper-convenient, ubiquitous media (Featherstone 2009).

What could be wrong with making media more accessible to the user, at least in the sense of access to an abundance of content, often personalized, on demand? Since the horse is well and truly out of the barn, it’s not my purpose to argue against it, but rather suggest that we pause to recognize the meaning of this ongoing shift in media distribution, in particular for audiences. What difference does it make when media come to us, rather than we go to media?

Many of us have shifted to subscribing to “media-as-a-service” rather than seeking out discrete purchases and rentals of media products (78% of Americans paid for a subscription video service as of 2021). Amazon, for example, has steadily shifted over time from selling physical media products (books and CDs), to selling or renting digital downloads (songs, e-books, TV shows), to the now more dominant model of media subscriptions.

All subscription streaming platforms have an incentive to keep their users spending time with the service and therefore to keep subscribing, in order to benefit from that steady revenue. In addition, many, like Amazon, benefit from the ongoing data about users that they use to sell digital advertising, product placements, and to inform future content creation. With the Prime membership in particular, media play a role in securing customer loyalty that reverberates across business areas. As Jeff Bezos once memorably quipped, “When we win a Golden Globe, it helps us sell more shoes.” The logic of surveillance capitalism drives strategies of platform enclosure.

Thus far, the so-called streaming wars have brought about a new “golden age” of television, or “peak TV,” with award shows dominated by series from streaming platforms like HBOMax, Apple, and Netflix. Certainly, at the tips of these services’ pyramids are high-budget series with top-shelf talent. But there is a lot of other content under the water line. When one of the main selling points of media is its convenience, the business incentives are to produce a large amount of content that is just “good enough.” The Disney+ subscription rocketed past many of its competitors because it has made so much memorable, iconic content exclusive to its service. Now it draws on its intellectual property (particularly the Star Wars franchise) to present a steady stream of original series of uneven quality (I’m looking at you, Obi-Wan), seemingly just enough to dissuade a fan to end the subscription.

Once, as consumers, we’ve sunk costs into a subscription, there’s an intrinsic motivation to consume media we have, in a sense, already paid for. This is even more pronounced with subscriptions that are bundled with other services, as is the case with the Prime membership, Apple One, and the Disney bundle, contributing to a greater sense of lock-in. How many of us are watching The Rings of Power because we happen to have Prime Video? And is being locked into the subscription because of the free shipping benefits of the Prime membership convincing us, perhaps, that we like it more than we actually do?

Chuck Tryon (2013) has argued that the age of ubiquitous media makes our relationship to media more casual, more informal, and less committed. The contrast between making plans, buying tickets, and going to a movie, compared to checking out a movie at home that is available on a streaming service, illustrates a different effort and commitment level that impacts the viewing experience, even beyond the difference in the screen and physical viewing situation.

When media come to us—at the time, place, and on the device of our choosing, with options often pre-selected for us by platform recommendation algorithms—it places the user at the center of the media experience. It is, in that sense, empowering, positioning media as something that should serve us, as individuals, at our convenience. Media made easy is exemplified by TikTok’s For You Page or FYP, curated by a “hyper-effective algorithm” that serves short-form videos according to the preferences of the individual user as predicted by past behavior and that of millions of other users on the app. The format is so habit-forming that time spent by kids and teens on TikTok has surpassed YouTube in just two years.

The shift I’m describing—from discrete moments of media consumption to consuming “media-as-a-service”—brings an accompanying shift in our audience subjectivity: from a “choosing subject” to a “served self.” There’s no question—being a choosing subject takes time and effort. In contrast, the served self prioritizes ease and convenience, and values the way platforms take over the labor and effort of research and selection by offering curated recommendations, pre-made playlists, or viral videos just For You. These are services with clear appeal and value given the massive amount of media and entertainment that is in theory accessible in the digital age. The served self implicitly agrees to let past choices dictate future ones, through mechanisms of platform surveillance. The way platforms construct their interfaces for the served self and not for the choosing subject is something you might feel viscerally when you decide not to watch any of the content being recommended on your streaming service. Most video streaming services do not easily reward browsing, a function of the interface which typically implies abundance, but is designed to conceal the fact that the catalogues are frequently more limited than they care to admit (Stewart 2016). Acting like a choosing subject in an environment designed for a served self is an awkward fit.

Of course, when the media-as-a-service model stops working for people, failing to entertain, they move onto other platforms and subscriptions, as Netflix learned earlier this year as its subscriptions actually shrank. The goal of platforms to enclose us within their services, where they can nudge and recommend us towards never-ending media consumption, is not inevitable. But together, the forces of surveillance capitalism, platform enclosure, and our own attraction to the convenience of media made easy are considerable. Among the many tools that platforms have at their disposal today to shape user activity and profit from it, their cultivation of the served self is a powerful one.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: mixtape by Tara Hunt

- Figure 2: Prime packing tape promotes various services in the “bundle” (author’s personal collection)

- Figure 3: netflix tv by Stock Catalog

Featherstone, Mike. (2009). “Ubiquitous Media: An Introduction.” Theory, Culture, & Society, 26 (2–3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409103104

Stewart, Mark. (2016). “The Myth of Televisual Ubiquity.” Television & New Media 17 (8): 691–705.

Tryon, Chuck. (2013). On-Demand Culture: Digital Delivery and the Future of Movies. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.