Television For Swing States

by: Henry Jenkins / Massachusetts Institute of Technology

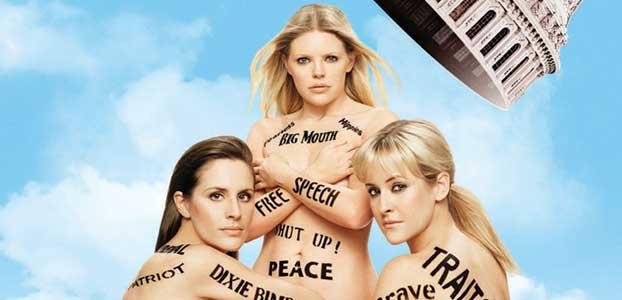

Dixie Chicks Controversy

It is now six months after the November 2004 elections and outraged Democrats have perhaps finally begun to accept the harsh reality that — and I’ll slide us into this slowly — John Kerry got more votes than any presidential candidate in American history — with the exception of George W. Bush. We aren’t talking about a defeat on the scale of Mondale or McGovern; the election turned out to be what we had anticipated all along — a squeaker. Both sides experimented with alternative media strategies; both sides tapped the power of popular culture and explored the potential of new media in an all out effort to mobilize their base, recruit new voters, and win over the undecideds. We can summarize the two campaigns through contrasting cultural reference points:

| Dixie Chick’s outrage over the Iraq War | The FCC’s outrage over Janet Jackson’s Nipple |

| “Bush in Sixty Seconds” | Swift Boat Captains for Truth |

| Michael Moore | Mel Gibson |

| “Deanie Babies” | Republican Bloggers |

| The Daily Show | Fox News |

| “Vote or Die” | Direct appeals to church groups |

| Air America | Clear Channel |

In each case, the Republicans added just a few more voters to their tally and that’s all it took.

Democrats saw popular culture as a way of reaching the “hearts and minds” of voters, yet their perspective was limited in so far as they understood democracy in terms of a special event, putting all of their effort behind defeating Bush and then feeling devastated when they failed to achieve that goal. Instead, we need to see citizenship as a lifestyle; the real change will come when progressives reframe the terms of the debate and construct compelling narratives which change the way we think about the micropolitics of everyday life.

George Lakoff’s Don’t Think of an Elephant! offers a compelling analysis of how progressives might recover from the 2004 defeat. Lakoff argues that the Democrats had the facts on their side but the Republicans framed the debate. To turn this around, the Democrats need to reinvent themselves — not by shifting their positions but by altering the frame. As Lakoff explains, “Reframing is social change…. Reframing is changing the way the public sees the world. It is changing what counts as common sense.”

In a simple yet suggestive analysis, Lakoff characterizes progressive and reactionary politics in terms of what he calls the Nurturing Parent and the Strict Father frames. According to the Strict Father model, Lakoff writes, “the world is a dangerous place, and it always will be, because there is evil out there in the world. …Children are born bad, in the sense that they just want to do what feels good, not what is right.” The strict father “dares to discipline” his family and supports a president who will discipline the nation and ultimately, the world. According to the progressive “nurturing parent” scenario, “Both parents are equally responsible for raising the children. …The parents’ job is to nurture their children and to raise their children to be nurturers of others.” Swing voters share aspects of both world views. The goal of politics, Lakoff suggests, is to “activate your model in the people in the middle” without pushing them into the other camp.

While Lakoff’s emphasis is on political rhetoric, his focus on the family is highly suggestive for television scholars given the medium’s relentless production of family melodramas and domestic sitcoms. We can see individual programs as tapping — and reinforcing — these frames, though television most often aims for a commercial sweet spot — one occupied by Lakoff’s “people in the middle.” Niche media outlets can and do focus their attention on red or blue America, but the broadcast channels must go purple.

We can see these pressures at work in a liberal show like The West Wing, which many have described as a “shadow presidency,” constantly framing a progressive response to the policies of the Bush administration. When the writers let Bartlett be Bartlett, the “POTUS” does what many of us hoped Howard Dean might do — represent the “democratic wing of the Democratic party,” addressing head on conservative and moderate objections. To do this, the series must acknowledge and rewrite more conservative perspectives, especially if it is going to attract and convince the “people in the middle.” Sometimes, it does so through the introduction of thoughtful conservative characters such as Ainsley Hayes or Clifford Calley who often argue against, more often compromise with the liberal protagonists. Other times, we see the pull of the program’s core content towards a more conservative framing of the issues (especially in the 2003-2004 season) where episodes seemed to embrace the Bush agenda whole-cloth. Perhaps, most spectacularly, the current season centers around the political campaign to determine what kind of leader will replace Josiah Bartlett. When the dust settles, it looks likely that both parties will have selected candidates that in reality neither party could nominate — Jimmy Smitt’s Matt Santos is a thoughtful Democrat who refuses to play the race card and Alan Alda’s Arnold Vinick is a principled and independent-minded Republican who refuses to play the gotcha game. Both are men who have strong appeals across party lines because they represent a balance between Lakoff’s strict father and nurturing parent models.

On the other end of the spectrum, 24 might be seen as the archtypial example of reactionary television, governed by the ongoing recognition that the world is a dangerous place and that the strong protagonist must do things that even his own government refuses to sanction. Week after week, 24 justifies the use of torture and the circumvention of civil liberties because there just isn’t enough time to do anything else. Yet, as reactionary as 24 can be, there are still hints of the nurturing parent frame which comes through at those moments when people place their personal loyalties — inside and outside of families — above everything else or conversely, when we see evil parents or duplicitous spouses who put their ideological commitments above the need to nurture and support their family members.

Lakoff uses the consumption of popular culture to discuss how these competing frames may interact within any given voter: “Progressives can see a John Wayne movie or an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie and they can understand it….They have a strict father model, at least passively. And if you are conservative and you understand The Cosby Show, you have a nurturing parent model, at least passively.” Popular culture allows us to entertain alternative framings in part because the stakes are lower, because our viewing commitments don’t carry the same weight as our choices at the ballot box. A progressive viewer may watch 24 without guilt while deciding to vote for John McCain might be a much bigger step.

And that brings us to what I am calling here television for swing states — programs like Jack and Bobby and Lost which consciously mix and match conservative and progressive signifiers. My father used to say that people who stand in the middle of the road get hit by cars going in both directions. Yet, I think we would be wrong to see these series as simply wishy-washy. Instead, such programs are doing important political work; they provide a common cultural context within which conservatives and progressives can debate values and within which independents or swing voters can play around with competing ideological visions. Such shows construct and test market hybrid political identities.

Jack and Bobby does this cultural work on two levels: through its critique of contemporary family life (as represented through the contemporary storyline) and through its construction of an alternative political future (through its representations of the McCallister presidency some decades later). Our awareness of Bobby’s political future ups the stakes in what is otherwise a fairly typical WB youth drama, transforming adolescent delimmas into world-changing events. Through a drama about a broken home, where Bobby must find his way between the competing demands of an overly-indulgent but subtly coercive mother and a tough love brother, we see a search for a coherent set of values which will guide the next generation of political leaders. The pot-smoking mother needs to be taught discipline; she is too quick to jump to politically correct conclusions; she can’t keep her mouth shut in social situations, which call upon her to be a mother first and an ideologue second. The brother’s punishing gaze often comes across as misogynistic; he needs to stop judging people; he needs to be taught to nurture. In short, the program finds both the strict father and the nurturing parent paradigms lacking. At the same time, Bobby is simultaneously depicted as innately good (as in the nurturing parent scenario) and as undergoing a moral education (as in the strict father paradigm).

Emerging at the other end of this contradictory child rearing process, we see a candidate who is decisively purple — “the Great Believer.” President McCalister is a complex balance of his brother’s self-discipline and his mother’s passion and principles, an independent who beats both Democrats and Republicans in a closely contested election, a minister who speaks about core values but respects everyone’s right to choose and holds nondenominational services at the White House. (West Wing fans will recall that the whole concept of “nondenominational services” was a flashpoint for Bartlett.) Each week, we get a new revelation about the person Bobby will become, revelations which sometimes swing to the right, sometimes to the left. Despite the series’s title, Bobby McCalister is no Kennedy but he may be a white boy version of Barack Obama.

If Jack and Bobby’s political subtext is often inescapable, Lost remains more implicit — and this may help to explain why the latter is more commercially successful. As Susan Sontag suggested long ago in the “Imagination of Disaster,” cataclysmic narratives often provide a context for sorting through core values. The shipwrecked characters have been cut off from civilization and need to form a new community, work through competing bids for leadership, learn to respect and trust each other. The series protagonist, also named Jack, represents another political hybrid — sometimes the strict father who must lay down the law, sometimes the nurturing parent who needs to understand where a character has been in order to help them to adjust to their present circumstances. If Jack and Bobby allows us to imagine a future where current political battle lines can be blurred, Lost invites us to imagine a world where we can rethink our political culture from the ground up. The allegorical quality of the series invites us to read it in terms of spiritual values but Lost never fully commits itself to a religious interpretation. Call it”nondenominational.”

Why should we care about television for swing states? As long as the overarching narrative of American political life is that of the culture war, our leaders will govern through a winner take all perspective. As long as the Republicans keep winning elections, Democrats can have little or no active role in shaping social policies — though, as we are seeing in the current social security debate, they can do a lot of damage along the way. Every issue gets settled through bloody partisan warfare when in fact, on any given issue, there is a consensus issue which unites Red and Blue America and on most of those issues, the consensus ends up looking more progressive than not. We agree on much; we trust each other little.

In such a world, nobody can govern and nobody can compromise. There is literally no common ground. Shows like Jack and Bobby and Lost create common ground from which we may construct and debate our fantasies about America’s future. Such shows are politically important because they generate dialogue between groups which, all too often, aren’t even speaking with each other. It is through such dialogue that a new political culture can emerge. And as I have suggested, such shows construct hybrid candidates who show how one can reframe progressive politics in ways that speaks to the “people in the middle.” If progressives study such shows, they may well learn to do what Lakoff is advocating — reframe the debate.

Image Credits

1. Dixie Chicks Controversy

Links

Rockridge Institute Interview with George Lakoff

George Lakoff Home

The West Wing

24

Lost

Swing State Project: Swing States and TV Advertising

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This Week on Flow

How to make this work

I am impressed with Dr. Jenkins’ optimism. His sense that television can contribute in positive ways to discussion in the public sphere is compelling. I find myself wondering, though, how citizens make the leap from talking “about” TV to reframing political debate. I think of a program like All in the Family that probably had an impact on the ways individuals talk and think about issues, but I’m not convinced it really had an impact on political debate. Is reframing the job of scholars who write about television? Or citizens who watch and talk with each other? How do we get from A (watching programs that offer a range of perspectives)to B (reframing politics in a way that allows compromise)?

Just one letter away

On its face, the problem presented by A and B is that they look so different: A is all straight and angular and B is pretty curvy. Within the visual frame, it is hard to imagine any commensurability.

But within the alphabetic frame, they literally couldn’t be closer. What is similar about both frames is that they are both socially constructed and situated, maintained and negotiated through circulation and use.

When people watch television, as Dr. Jenkins points out, they have the opportunity to “try on” competing perspectives and identities to see how they fit. The powerful, resolute certainly of Jack Bauer on 24 may feel justified in the way it hangs on the shoulders, but sometimes it feels as if there is some kind of residue on it that transfers onto your skin: you may not like wearing it for too long or you can start to feel sick. The way the mantle of communal fellowship among the staff of The West Wing envelops you may make you feel warm, and the inner lining has a fuzziness that just feels nice on your skin. But you can start to wonder whether the garment itself is maybe a little too insular–how will you know when its time to change?

In our liberal democracy, daily decisions are made by our representatives. If we want to influence policy, we need to appeal to those representatives, which means we need to make persuasive arguments rooted in compelling evidence. The public texts we share, like televisions shows, popular music and novels, serve as a common cultural wellspring from which we can draw that evidence and shape those arguments. We reframe politics to allow compromise only when the available texts for discussion imagine politics as compromising. While the tempo of this process is hardly revolutionary, it ultimately creates a more stable foundation for social interaction. Seeing politics in this way–as always articulated with social life–argues even more stringently for now as the time to begin working on ways to shape and guide the debate: if it will take longer to get there, all the more reason to start moving now.

PS–my apologies for the heavy use of metaphor above. I don’t know what came over me, but I’ll leet it stand as is anyway ;)

How do we move from TV to Politics

1. We can use popular media texts as rallying points for political activism. See for example the ways Greens organized around Day After Tomorrow, fundamentalists around Passion of the Christ, democrats around Michael Moore, etc.

2. We can see the discussion lists around such shows as spaces where people of diverse political backgrounds gather and converse. As they talk, they discuss not simply the shows but their implications. In my forthcoming book, Convergence Culture, I propose, borrowing from Pierre Levy, two related concepts: The text as a cultural attractor (that is, as something that draws together folks who share some interests in common) and as a cultural activator (that is, something which sets their creative and speculative activity in motion.) I am arguing that we see these discussions as political on their own grounds.

3. Parties, activists, etc. should be monitoring the political discourse on these popular shows as a way of identifying ways of framing the issues which might speak to a larger public. How many of us have wished for a Democratic candidate who sounded more like Josiah Bartlett?

Anyway, I offer these points as a more explicit statement of what was implicit in the column itself.

Pingback: FlowTV | The West Wing–A Hyperreal, Not a Reality Show

Ohhhh!

Wow, Henry Jenkins has made me think a lot about this issue. I was previously unaware just how powerful media is in constructing our political viewpoints. I would like to respond to Marnie Binfield’s post that doubts the influence of television’s framing of subjects. I feel that Jenkin is trying to imply that the fundamental structure of a t.v. show can enormously impact our world view and consequently our political views. If a show such as “24” presents its characters’ environment as a dangerous place that needs people in power to go out and make it safe, then audiences will come to accept the notion that we live in a dangerous world that needs America to go out and “make it safe.” However, if you were to reframe the show and present the characters in an environment that is relatively safe and doesn’t need to be policed, then audiences will grow familiar with this world view and accept the notion that the world is safe and if America didn’t meddle in other countries affairs, it would continue to be safe. Basically, it boils down to if you constantly present a world that consistently agrees with conservative beliefs, then audiences will grow to grow to accept conservative beliefs as truth. Same would be true if you presented a liberal world-view. This leads to a very interesting and very problematic aspect of television. If television can influence our fundamental view of the world, then its idealized structure can distort our understanding of the world and changes taking place within it. For example, if we are constantly exposed to characters who live in the beautiful, green landscape of California (or any other picturesque places in the world), we can become accustomed to the notion that that is the way the rest of the world is; that most of the world is still healthy and we need not worry about depleting our environment. We become familiar with this world-view and any arguments that deal with how America or other countries are destroying the earth seem foreign to us. Why would we even think that there are sad, poverty-striken places on earth if we are never exposed to them; if whenever we turn on the tv, we see only the beautiful parts of the world. And when we do see the bad parts, its usually when America is going in to fix it. After reading Jenkin’s article, I now understand how it is not the discourse within a show, but the show’s framing that influences our world-view.

Pingback: FlowTV | If We Are So Smart….