Micro-Ethnographies of the Screen: The Supermarket

As I enter my neighborhood supermarket, I pass beneath a television monitor mounted about five feet above my head. I glance up at the screen and see myself enter the store, the sliding glass door to my back and a rather bored looking young security guard, arms crossed leaning against the lotto machine, to my side. A small camera attached to the base of the monitor provides a continuous stream of images throughout the day. I suppose this screen must serve to warn any potential thieves that they are being watched. As a subject of the camera and its screen, I am now either a dissuaded thief or, perhaps most likely, an oblivious innocent as I notice that most shoppers entering through this door fail to look up at the surveillance screen. Whatever intention the store managers had in displaying this screen at this location, it goes for the most part unseen. I only notice this surveillance screen because I have come to this store with the express intent of seeing the screens that I normally ignore or overlook.

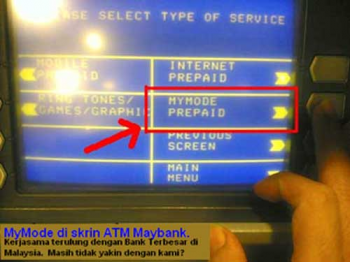

I grab a shopping cart and begin my trip through the aisles. At the rear of the store, past the bottles of organic juice, baggies of instant salad, and cartons of lactose free milk, stands a bank machine idling next to a full service teller window for a large bank chain. Whereas the shopper in relation to the screen display at the store entrance is given over to the identity of proto-thief or would-be bandit, the screen of the bank machine performs a routine function — dispensing cash, accepting deposits, informing on account balances, and the like. While the bank screen differs from the surveillance screen in that there is no starring role for the subject on the screen itself, the user does become the focus of the screen during the transaction. Thescreen directly addresses the user by delivering an instruction or by asking a series of questions. Insert card. Instant cash? Do you want to print a statement of your last ten transactions? Graphics appear on the screen, short animations that serve to entertain — if you can call it that — and to provide the user with a logo-like branding of the bank’s identity. Figure 1 provides a sample screen shot of the image as it flits past the viewer/user. To this screen, I am one of the bank’s valued customers.

Figure 1: Bank Machine Screen

Concluding my business at the bank machine, I load my shopping cart with food and arrive at the checkout line. The final screen that presents itself is a flat screen monitor mounted on a pole above the cash register about eye level with me as I transfer my food selections to a conveyor belt leading to the cashier. This screen rather loudly advertises items for sale in the store, local businesses, and upcoming programs on the Food Network while providing recipes for shoppers who have remembered to bring their notepads to the line. This “check-out” screen signals the eventual demise of the ubiquitous, decades old magazine rack located at the end of most cashier aisles (Figure 2). While in the past one has been offered the opportunity to glance through, and hopefully purchase, Time, Newsweek, or the Weekly World News, now one may gawk at a video screen conveniently placed for consumption. I recently became excited by the teaser for the season premier of Emeril Live and learned how to cook a nutmeg flavored, orange glazed ham (although I failed to bring my pocket notepad, so I have forgotten several of the steps in the process).

Emirel Live

While each of these supermarket screens participates in the ritual of grocery shopping, each serves a different function and ascribes a different subjectivity to the shopper. The screen mounted overhead at the entrance door serves to warn away shoplifters. Its image is silent, blurry, and continuous. The bank machine screen interacts with the shopper signaling activity through a series of beeps and music. Its image is both fragmented and functional. Finally, the checkout screen serves to distract shoppers as they wait in line to pay for their chosen food stuff. It is bright, sharp, loud, and rapidly edited. If the other two screens dissolve into the designed environment of the supermarket — each item for sale and each surface for display beckons to me while feigning a ubiquitous naturalness — then this final screen proclaims its need to seduce and distract me. In so doing, like an insecure performer on stage, it displays its newness to the supermarket scene. The design of product packaging and display advertising draws on a lineage leading back to the beginnings of consumer capitalism, while this checkout screen stands uneasily as a bastard hybrid of the magazine rack, the candy display, and the television commercial.

As media theorist Vincent Mosco suggests: “the real power of new technologies does not appear during their mythic period, when they are hailed for their ability to bring world peace, renew communications, or end scarcity, history, geography, or politics; rather, their social impact is greatest when technologies become banal.” Public screens, even as they address us, attempt to blend in, to deflect our attention. During my previous trips to this supermarket, I had ignored the surveillance screen, cursed the bank screen for non-responsive buttons, and shielded my eyes from the checkout screen. Yet, nevertheless, each of these screens had called to me and I had on previous trips responded with the subjectivity that they — or to be less anthropomorphic, their designers — intended for me to display. What this micro-ethnographic glance — a frame of mind rather than a research method — reveals to the subject of these screens (in this case myself) is that these screens make us do things — refrain from shoplifting, withdraw cash, bake a ham.

Work Cited

Vincent Mosco. The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power, and Cyberspace. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004. 19.

Links:

Urban Screens Conference

Surveillance and Society

Image Credits:

2. Emeril Live

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV » This Week on Flow… (7 October 2005)

point-of-sale systems and demographics

As part of a major renovation, in 1999 or 2000 a central Austin HEB store I used to shop at installed large, bulky TVs above every other checkout lane. Unlike POS screens, these screens were installed to serve a single purpose — to occupy the attention of customers while they are waiting. The TVs mainly displayed CNN or Headline News, and for me were far more interesting (if not entertaining) than bold gossip rag declarations. CNN in this context was a safe choice considering the makeup of the supermarket audience at this store — white, middle-class and student shoppers — whereas in other parts of the city, Univision might hold more shoppers’ attention.

The continued addition of computers and clear LCD screens to POS systems have contributed to a streamlined, “easier” consumer experience, whether the good consumed is food, cash, gas, drinks, or even lottery tickets. Unfortunately, this application of technology has also allowed retail establishments to become another site of multimedia content — advertising, TV promos, news tickers… And we need to know more about the companies that are in business to produce this content, and what audiences they are catering to. How specialized could this content get in terms of market demographics and sites of viewing? For now, it’s probably a safer endeavor for niche markets such as upscale groceries — HEB has introduced advertised specials images on its LCD POS screens, but would need a ton of varied programming to keep the attention of its mass clientele. But Leopard’s micro-ethnography does point to a serious need to address how media is produced for and consumed in these complex consumer environments.

Be sure to check out. . .

Anna McCarthy’s _Ambient Television_ (Duke, 1999?) which offers some really useful and original ways of framing this topic within media studies, ethnography, history etc.