Where the Boys Are: Postfeminism and the New Single Man

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY FEATURE COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW REGULARLY ACCEPT SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE VISIT OUR “CALLS” PAGE FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

John: Do you ever think we’re being — I don’t want to say sleazy ’cause that’s not the right word, but a little irresponsible?

Jeremy: No! One day you’ll look back on all this and laugh. And say we were young and stupid. A couple of dumb kids running around. . .

John: We’re not that young.

– Wedding Crashers (2005)

Postfeminist representational culture is preoccupied with distinctions of age and generation and it is adept at searching out and “rehabilitating” those who don’t fit its heteronormative, consumerist, domestic script. While in this respect its most frequent target has been the single woman, recent popular culture reflects an increasing interest in the single man. In a (perverse) spirit of gender egalitarianism, deficient/dysfunctional single femininity is now increasingly matched by deficient/dysfunctional single masculinity in a number of high-profile films and television series.

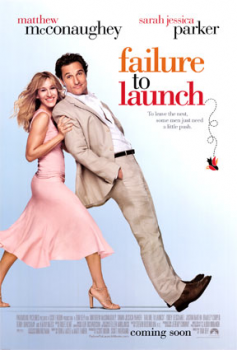

A cluster of 2005 and 2006 films (The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Wedding Crashers, Failure to Launch and the upcoming Mama’s Boy and You, Me and Dupree) stage anxiety about the uncoupled thirty or fortysomething male and his failure to take up his proper role in the social order. In Failure to Launch Tripp (Matthew McConaughey), a 35-year-old still living (and entertaining) at home, is the subject of an attempt by his parents to dislodge him. They hire Paula (Sarah Jessica Parker) a “professional interventionist” who fakes a romance with Tripp but winds up falling for him. The film’s device for staging Tripp’s “unnatural” state is a series of hostile encounters with animals in scenes of outdoor leisure. He is attacked by a chipmunk while biking, a dolphin while surfing and finally a lizard while rockclimbing. For those viewers who miss the point, Tripp’s predicament is pithily diagnosed by his friend who tells him, “Your life is fundamentally at odds with the natural world. Nature rejects you.”

Similar preoccupations with bachelorhood structure this season’s Modern Men (WB), Four Kings (NBC) and the upcoming What About Brian (ABC) on television. Meanwhile the entry for Failure to Launch on the Internet Movie Database includes a thread of 157 posted responses in response to an initial testimonial entitled “I Still Live at Home and I Like It!” (Ensuing debate ranged widely from the comparative costs of establishing financial autonomy in different regions of the country, to the gender norms that would seem to penalize men more heavily for living with their parents in adulthood, to the nature of “meaningful” work and compensation.)

Media fictions like these (and debates about them) play out against a backdrop of intermittent media panic about male achievement (a flurry of press coverage in recent months drew attention to the fact that women now outnumber men students at many universities) and the publication of new polemics in defense of the naturalness of patriarchy (Philip Longman’s “The Return of Patriarchy” in this month’s Foreign Policy) and the value of manliness (Harvey Mansfield’s book Manliness). The fear that the single man is not taking up his proper place in the domestic order has accompanied a re-positioning of the single woman that entails a certain ambivalent celebration of some such women “taking responsibility” (always a virtue in the society of managed selves) for their own procreative and economic status. The financially secure new single woman has been widely profiled including in USA Today‘s Valentine’s Day publication of “Dream House, Sans Spouse” a feature on the rising rates of female home ownership. According to the article, single women not only comprise one-fifth of all home buyers, they also buy at double the rate of single men (a striking departure from homeowning statistics in 1981). Two weeks ago in a cover story unfortunately titled “Looking for Mr. Good Sperm,” The New York Times Magazine addressed the phenomenon of single professional women buying sperm and managing conceptions on their own before losing fertility. In a quintessentially postfeminist scenario women are now often seen to be equally as or more adept than men at transitioning to an environment in which intimacy is fully commercially transactable.

The single man represents a compound problem and his offense registers at both a familial and an economic level. Not only does the stay-at-home single man spoil the scene of approved intergenerational domesticity, he is also likely to be marginally employed and/or an economic “poacher.” Wedding Crashers‘ Jeremy (Vince Vaughn) and John (Owen Wilson) illicitly take part in the bridal economy, bringing sham gifts and enthusiastically consuming the catering in their bid to meet women for sex. In Failure to Launch Tripp “treats” Paula to lunch on a client’s boat he tries to pass off as his own. In You, Me and Dupree a newly-married man’s friend (Wilson again) becomes a long-term houseguest after he takes time off from work to attend the wedding and is fired as a result. The single man living at home has not set up his own household and he does not dedicate himself to the economic provision of others. Even Wedding Crashers‘ Jeremy and John are repulsed by Chazz (Will Ferrell) the “innovator” whose social model they have ascribed to, when they discover he lives with his mother and has moved on to preying upon grieving women at funerals.

The emergent “problem” single man offers an opportunity to think about the nature and function of postfeminist masculinities in current popular culture. Any such consideration should bear in mind the way this figure works to obfuscate the ideological agenda behind the current cultural celebration of women who return home either as chastened former professional women, divorced women, single mothers or carers for elderly parents. The single man’s (relative) dependency puts him in the position of usurping the retreatist postfeminist woman and in their desire to expel the single man from the scene of the family home these fictions tend to reinforce its appropriateness for women. In unlocking the single man from his “unnatural” state these films also make him a promise: that he will not have to forego bachelor pleasures upon the achievement of economic independence and exogamous emotional commitment. There, is after all, no justification for languishing in arrested development when bachelorhood prerogatives now extend past bachelorhood into commitment and marriage. In the era of the “gentleman’s club,” the bachelor party vacation, and the friendship group vacation where partners stay home such recreational prerogatives are extended far past youth. At the conclusion of Wedding Crashers the newly formed couples of Jeremy and Gloria and John and Claire happily drive off to crash a wedding together.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

Men in TV

This article makes me think about how the gay male has been represented in both film and television lately. It seems that a gay character is either one of two extremes; dating around and characterized as a slut or in a committed relationship. I am thinking of Will and Grace and Six Feet Under in particular. I could be over generalizing the media, but from the shows and films I have seen, it seems like the gay male is never shown as exclusively single or even old or aging.

I am definitively sold on Wedding crashers II, this time with women coming up with the best pick up lines for boys. I bet that Wedding Crashers II will be a more intelligent and funny movie than the original which ultimately adds nothing to the male adolescent power fantasies over women.

Injury Politics

This spate of films and televisual texts also reinforce the current dogma of the injured white male who claims specificity as a means of reinstalling dominance — multiculturalism’s lessons turned against itself. From Desperate Housewives to 24 (Jack Bauer as white male beseiged by not only terrorists but women spies, bosses, former friends, and even his own daughter who also attack him physically and emotionally as a man), the current media depictions of white men who suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous women and minorities.

Pingback: FlowTV | Special Features on Flow Needs You!

Reversal of power

Until reading this article, I had not thoroughly contemplated the role of men in the forthcoming postfeminist era of television. Television and film’s portrayl of the aging single male is less focused on the praise-worthy bachelor lifestyle, and more on the flaws of the men that have deemed them unsuitable to find a mate. Interestingly enough, women have taken over the “male” role and save these male leads from a life of loneliness and squalor, and do so in a way that portrays their ultimate feminine power that has the ability to persuade a man to change his ways. My question is why does one gender have to dominate the other in order bring about relationship satisfaction? In reality, relationships are unhealthy if one member dominates the behavior of the other. Yet in television and film it is necessary for this sort of conflict to arise, and for one partner to succumb to the other’s demands in order to keep the relationship alive. I challenge the television industry to create a show that portrays a healthy couple, that does not need to have their relationship subjected to the conflicts that arise from an imbalance of power between partners.

“Succumbing to the other’s demands, dominating behavior…” sounds like a healthy relationship to me. Well, maybe the binding force of a reality-based relationship to say the least. Domination perceived not as intention, but a side-effect of the learn, teach, compromise cycle of a relationship. Maybe tv would syndicate if only they had a couple from which the show could be based?

With such a severe shift occurring in gender dynamics in real life, television is put in the position of either portraying changing gender roles accurately, and thus risk offending people from both parties concerned, or putting a more upbeat spin on things. It is obvious which decision which has been reached. From the buffoonish man-boy who still lives with mom and dad to the gorgeous career-woman is independent, yet a romantic at heart, television today seems to be portraying such clichéd and accepted gender stereotypes that they could not possibly offend anyone. Such silly archetypes are far too corny and familiar to be called into question. Dating back as far as Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, when the hard-headed and juvenile Petruchio takes it upon himself to woo the tempestuous and independent-minded Kate, audiences have embraced the idea of the emotionally underdeveloped man suddenly growing up and appealing to a strong woman’s softer side.

Regardless of a character’s gender, they all seem to be heading towards the same finish line: get married and start a family. This appears to be the ultimate goal for everyone on television, whether they realize it or not. However, while single adult males in the media are goaded into starting a family by society, women on television are compelled to do so because of their own personal desires. Where once women on television were able to function as complete characters without a significant male in their lives, such as Murphy Brown, now single women over age 30 on television are always concerned first and foremost with finding a man and getting married, no matter what else is going on in their lives. L.S. Kim summarizes this idea in her essay “Sex and the Single Girl” in Postfeminism when she writes, “the portrayal and concept of independent women who are challenged by their independence…has been replaced by the depiction of independent women who are shown as unhappy because of this independence.” Perhaps adhering to such traditional values as the desire to settle down and get married allows programs to take risks in other areas. The women in Sex and the City could have promiscuous sex with a different partner in each episode, because the audience was told that they were all just looking for true love. However, in a society that is so concerned with progress and the acceptance of different lifestyles, television shows seem oddly preoccupied with having their characters all end up in the same place.