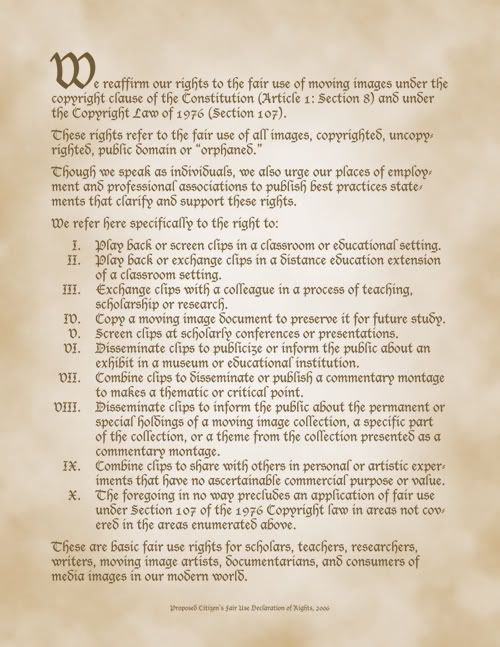

A Fair Use Bill of Rights

“It was time to stir.

It was time for every man to stir.”

–Tom Paine, Common Sense, 1776

We reaffirm our rights to the fair use of moving images under Article 1: Section 8 of the Constitution, the Copyright Clause1, and under the Copyright Law of 1976 (Section 107).2

These rights refer to the fair use of all images, copyrighted, uncopyrighted, public domain or “orphaned.”

Though we speak as individuals, we urge our places of employment and professional associations to publish best practices statements that clarify and support these rights.3

We refer here specifically to the right to:

I. Play back or screen clips in a classroom or educational setting.

II. Play back or exchange clips in a distance education extension of a classroom setting.

III. Exchange clips with a colleague in a process of teaching, scholarship or research.

IV. Copy a moving image document to preserve it for future study.

V. Screen clips at scholarly conferences or presentations.

VI. Disseminate clips to publicize or inform the public about an exhibit in a museum or educational institution.

VII. Combine clips to disseminate or publish a commentary montage to make a thematic or critical point.

VIII. Disseminate clips to inform the public about the permanent or special holdings of a moving image collection, a specific part of the collection, or a theme from the collection presented as a commentary montage.

IX. Combine clips to share with others in personal or artistic experiments that have no ascertainable commercial purpose or value.

X. The foregoing in no way precludes an application of fair use under Section 107 of the 1976 Copyright law to areas not enumerated above.

These are basic fair use rights for scholars, teachers, researchers, writers, moving image artists, documentarians, and consumers of media images.

Analysis

The “Fair Use Declaration of Rights” proposes that teachers, media critics and moving image artists see fair use collectively and as concerned citizens–not simply as members of interest groups.

The “Fair Use Declaration of Rights” focuses on fair use as a political issue as well as a legal one.

The words of the Declaration echo those of the American Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights in quite conscious ways. They echo other declarations of collective identity and purpose as well.

Though best practices statements by individual professional associations are important for all of us who critique, parody and contextualize the media images that surfeit us, surround us, and bombard us daily, we also need to unite under a single banner.

Fair use is, put quite simply, the right of reply. That right applies as much to my next door neighbor as it does to the teachers, writers and media artists who confront, explain, organize, quote or teach from these images daily as part of their jobs.

What the Fair Use Declaration of Rights is intended to signal is a turn from the defensive stance so often adopted in response to law and lawyers on this issue, to a position of forthright, positive, and proactive assertion.

These are our rights from the very beginning. The lawyers work for us, not other way around. It's time to leave the bargaining table where so often compromise means, finally, giving ground, and take a forceful stand on this issue.

What we are saying when we subscribe to a “Fair Use Bill of Rights” is that fair use is a “right,” not a “defense.” As one prominent intellectual property attorney, who happens to work for a major research University recently put it: “fair use–use it or lose it.”

REFERENCES

The publications and statements listed below are by no means exhaustive. Rather, they represent a very selective list of some notable items in a growing literature on fair use that has been developing over the past forty years, and continues to grow.

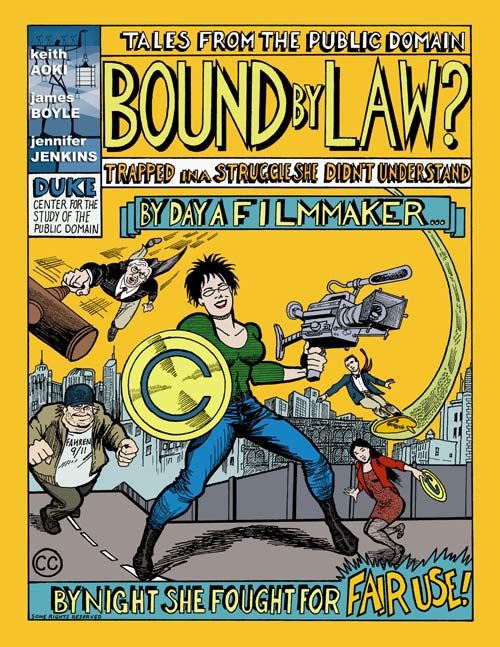

Aoki, K., Boyle, J., & Jenkins, J. (2006). Bound by law? Tales from the public domain [Legal education comic book]. Durham, NC: Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain. http://www.law.duke.edu/cspd/comics/zoomcomic.html

Barlow, J.P. (2006, March/April). Is cyberspace still anti-sovereign? California Magazine 117:2. Also available: http://www.alumni.berkeley.edu/calmag/200603/barlow.asp

Center for Social Media/Washington College of Law Report (November 18, 2005). Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use. Statement endorsed by Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers, Independent Feature Project, International Documentary Association, National Alliance of Media Arts and Culture, Women in Film and Video. Washington, DC: American University School of Communication/Center for Social Media. Also available: http://www.centerforsocialmedia.org/fairuse.htm

Downhill Battle web site (2006). Grey Tuesday: Free the grey album November 24, 2004. Retrieved July 27, 2006 from http://greytuesday.org

Kunzle, D (1989). In Fair use and free inquiry: Copyright law and the new media. Timberg, B., eds. 2nd ed. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishers (21-32).

Lange, D (2004). Proposal concerning compensation and rights to use copyrighted clips in documentary film. Presented at “Framed! How Law Constructs and Constrains Culture” conference sponsored by the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain and the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival at Duke Law School, April 2, 2004.

Lawrence, J.S. (1989). Copyright Law, Fair Use and the Academy. In Fair use and free inquiry: Copyright law and the new media. Timberg, B., eds. 2nd ed. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishers (3-19).

Lawrence, J.S. & Timberg, B.(1989). Conclusions: Scholars, Media and the Law in the 1990s. In Fair use and free inquiry: Copyright law and the new media. 2nd ed. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishers (364-372).

Leval, P.N. (1990). Toward a fair use standard, Harvard Law Review 103:1105.

Negativland. Fair Use: The Story of the Letter U and the Numeral 2 (1995). [with CD]. 1920 Monument Blvd, MF-1, Concord CA 94520, fax 510-420-0469: Seeland Publishers. Available also through: www.negativland.com.

Rosenfield, H. (1989). The American constitution, free inquiry and the law). In Fair Use and Free Inquiry: Copyright Law and the New Media 2nd ed. (281-304).

Timberg, B. (1989). New forms of media and the challenge to copyright law (1980). In Fair Use and Free Inquiry, 2nd ed. (210-230).

Timberg, B. (2006). A Fair Use Declaration of Rights. Carolina Communication Annual Sept 2006, Robert Westefelhaus, College of Charleston, ed. (12-16).

Timberg, S. (1980). “A modernized fair use code for visual, auditory, and audiovisual copyrights: Economic context, legal issues, and the Laocoon shortfall. In Fair Use and Free Inquiry, 1st ed. (305-336). Later version published in Northwestern University Law Review (1981) 75:101.

For the work of other leading legal theorists on this issue, see Lawrence Lessig, Peter Jaszi, Laura Gasaway, Pamela Samuelson, and Siva Vaidhyanathan. Teachers of law and legal theorists are speaking up. Where are the rest of us?

Image Credits:

Aoki, Jenkins, Boyle from the Center for the Study of the Public Domain. Also available here.

PDF document: Written by Bernard M. Timberg, designed by James Harman.

Please feel free to comment.

- Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution reads: “The Congress shall have Power…To promote the Progress of Science and the useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their Respective Writings and Discoveries…” Cited in Harry Rosenfield, “The American Constitution, Free Inquiry and the Law,” John Shelton Lawrence and Bernard Timberg, Fair Use and Free Inquiry: Copyright Law and the New Media, 2nd ed., 1989, p. 289. [↩]

- Section 107 of the Copyright Law of 1976 reads: “Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use. Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include – (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors. [↩]

- An outstanding model for a fair use best practices statement that has been used by other professional associations was issued by the American University Washicngton College of Law and Center for Social Media in November 2005. It is entitled a “Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use, and was written in association with the Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers, Independent Feature Project, International Documentary Association, National alliance for Media Arts and Culture, and Women in Film and Video, Washington, DC chapter. A complete version of the statement can be found here. [↩]

Pingback: FlowTV | Launch Texts, Rebound Texts and Commentary Montage: Al Gore’s Appearance at the 2007 Academy Awards

greg roderick