Racebending the “Superhero Girlfriend”

Ravynn K. Stringfield / William & Mary

The “superhero girlfriend” as a trope is a personal point of fascination. Not quite a princess or a Bond girl, only sometimes a damsel but often in distress, these characters, primarily women, have moral codes in line with their respective heroes, often boost an independent streak and yet still typically operate as bargaining chips when villains use them to either incapacitate or bend heroes to their will. My column “Superhero Girlfriends Anonymous” at Catapult explores the contentious histories of superheroes’ partners, who frequently serve as moral mirrors, and delves into my own ties to these characters in comics media. However, I have yet to think through contemporary comics-inspired media’s recurring desire to racebend superhero girlfriends, often in film and television adaptations.

At face value, racebending superhero girlfriends—which can often look like casting a Black actress in the role of a traditionally white character—is a measure of representation. But once the initial thrill of seeing someone who looks like you on the screen or on the page wears off, many viewers and readers become disenchanted and dissatisfied with stories that either sideline these characters or perpetrate misogynoir. Often these characters, whom TikTok media critic @DaejahTalksTV calls “Chocolate Dipped Barbies, ” are not written with an understanding of the cultural nuances that come with incorporating a Black character. In essence, despite these casting changes, these characters—like Iris West-Allen, played by Candice Patton, in CW’s The Flash, for example—are often still written as though they are white, under the guise of promoting diversity.

@daejahtalkstv Reply to @rosebychoice5 ♬ original sound – Daejah

One of the ways creators and consumers can make sense of these types of remixes in fantasy narratives is to deeply engage with questions of world building race. Tracy Deonn, author of the New York Times Bestseller YA fantasy novel, Legendborn, explains this as the process of accounting for cultural specificities and nuances that are going to matter to a character that may not be immediately translatable to every reader or viewer. In an interview for Dreaming in the Dark podcast, Deonn says:

“I talked with my friend Bethany C. Morrow about this, about world building Blackness. […] When you write fantasy, particularly contemporary fantasy, world building is important in fantasy as a genre anyway…but people don’t talk about world building identity. They don’t talk about what it means to really world build cultural identity into the book… When you write contemporary fantasy, you have to allot for the things that are gonna matter to this character, not every reader is gonna understand right away.”

For writers of comics media who now are working with Black actresses portraying superhero girlfriends, this means giving these characters the space they need to exist fully in the world.

As someone whose dream writing project would be to craft a Black Lois Lane story, this context and these questions are often at the forefront of my mind. What does it mean to remake mythic characters with Black girls in mind? What does racebending need to do to successfully make these sorts of changes work? Why is this sort of remixing a useful practice, if at all? What would it mean to write these women as complex and not used as bargaining chips in the Diversity Olympics, with each studio trying to bring in the most medals? And questioning how we find utility in these types of projects can coexist with questioning whether this is where we should devote energy at all.

There are a number of ways in which these types of projects can be useful. As an offshoot of the argument for greater representation of Black women in comics media, more visibility will offer those who may find comics and its fandoms daunting and sometimes hostile an entry point. (For more on digitalization and diversification of comics encouraging new readers and fans, see comics scholar Adrienne Resha’s “The Blue Age of Comic Books.”) With entryways and starting points more visible, new audiences demand more and different types of stories and storytelling.

As it pertains to the superhero girlfriend as a trope in particular, this is one way for Black girls to see them loved in iconic, even mythic ways, that are the stuff of legends in the mainstream. When Black women and girls are constantly boxed into stereotypes such as the overextended caretaker “Mammy” or the unlovable and aggressive “Sapphire,” they are often saddled with the responsibilities of becoming a moral compass or a problem solver to the white protagonist as a Magical Negro in fantasy narratives, a dilemma Africanfuturist writer Nnedi Okorafor writes about in a 2004 Strange Horizons essay. To have Black girls enter into conversations about media because their relationship to the text is “love interest” can change the narrative about who Black girls can be in both stories and the world.

And, finally, there is utility in these stories simply because there are Black people who want to write them. The question of love should factor in, not only for characters in these stories, but for the people on the other side who are creating them. Calling for Black joy should not be a call that is limited to the screen or the page; Black love can also be having the opportunity to bring one’s unique spin to a long beloved character or a team. Having Black writers and creators become integral parts of the storytelling also gives them opportunities to be central to the meaning making and interpretation of the myths we love.

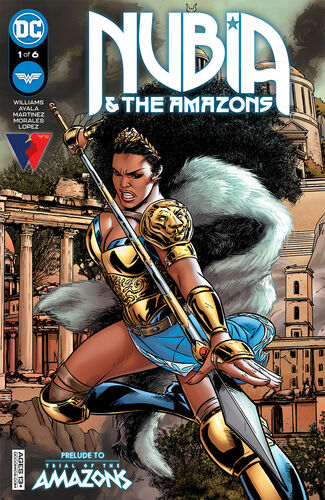

All of this is not to discount the work many Black writers are doing to introduce new Black characters into the comics canon or bringing already existing Black characters in canon to the forefront. There is currently excellent work being done revitalizing Milestone comics characters like Icon, Rocket, and Static Shock. N. K. Jemisin writes a new Green Lantern comic series, Far Sector, featuring a Black woman named Jo Mullein, and in doing so expands a canon where there can be a plethora of Green Lanterns, all with their own histories. Comics writer, critic and historian Stephanie Williams is doing both by breathing new life into Nubia, Wonder Woman’s twin sister, with her miniseries Nubia and the Amazons, firmly positioning her as a Queen of the Amazons, while introducing new important stories and characters into the canon, such as introducing a Bia, a character believed to be the first Black trans Amazon.

Multiplicity is a valuable tactic as creators strive to saturate media with all types of narratives about Blackness, including those where Black people are the center of superhero narratives and love stories. There is room for shifting the landscape of comics makeup from a number of vantage points. That said, all of these perspectives should be open to critical questioning. Racebending iconic characters is a way to rethink Black peoples’ relationships to mythic narratives, and it offers a window for creators and consumers to question what it is we actually do want out of our media.

Media Credits:

- Iris West-Allen in The Flash as a speedster

- Posted to TikTok by @daejahtalkstv on December 8, 2021

- DC’s “Nubia and the Amazons” Vol. 1 (2021)

“Claiming Legends & Legacies.” Dreaming in the Dark from Spotify, 28 October, 2020, https://open.spotify.com/episode/1n2oyUcRLqG1FMgl9GDwPv?si=8022635bff1f4764.

Okorafor, Nnedi. “Stephen King’s Super-Duper Magical Negroes.” Strange Horizons, 25 Oct. 2004, http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/articles/stephen-kings-super-duper-magical-negroes/.

Resha, Adrienne. “The Blue Age of Comic Books.” Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, vol. 4 no. 1, 2020, p. 66-81. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ink.2020.0003.