An Alternative Gem: The Spectacle Theater’s Unique Operative Structure

Kate Elora Rogers / The University of Texas at Austin

Of the hundreds of cinematic spaces in New York City, the Williamsburg bodega-turned-microcinema Spectacle Theater occupies a unique and significant sphere in contemporary exhibition. Since its inception in 2010, the volunteer-run collective has shown screenings everyday (pivoting to virtual screenings in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic) and relies on donations to maintain operations (Rapold Criterion.com). According to one Spectacle programmer, Steve Macfarlane, in 2015, the theater exists to “show movies that were either lost, forgotten, or both. All shows would cost $5. Nobody would get paid; anybody with an interest in getting involved—taking tickets, editing previews, writing program notes, designing artwork, curating series or all of the above—was welcome” (Macfarlane BKMag.com). This vision of Spectacle as a collective erases power structures typically seen in hierarchal curatorial and managerial roles at other film exhibition institutions. Fittingly, former Spectacle programmer Jon Dieringer shares that, “most of us intimately involved [with Spectacle’s founding] weren’t coming from or connected to traditional film institutions” (Rapold Criterion.com). This background, untethered from the structure of formal institutions, is integral to Spectacle’s formation and distinct vision to function through collective decision-making.

Spectacle’s specific approach to programming and operating a theatrical space bears a deeper examination, particularly considering the precarity of DIY spaces such as microcinemas. Here, “DIY” or do-it-yourself refers to the theater’s mission as a “collectively-run screening space in Brooklyn, NY, established and staffed by hard-working, cinema-loving volunteers” (“About” spectacletheater.com). This volunteer labor and non-institutional structure places the power equally and directly into the hands of the collective’s members. In light of the coronavirus pandemic, the Spectacle Theater has feasibly been able to shift to virtual programming (still at its $5 ticket for shows without a guest), elevating its ability to increase accessibility to audiences beyond the cinephile community of New York City. This visibility only strengthens the case to explore a venue bound by the free labor of its volunteers and their love of all films strange, unknown, and lost. In examining paratexts of the Spectacle’s film screenings, such as original program descriptions, trailers, and tweets it becomes clear how discourse in its presentation of its programming functions as a strategy of resistance to dominant film exhibition venues.

In Raymond Williams’ tracking of the evolution of the word and usage of “culture,” he notes the hostility that arose with notions of high and low culture, particularly in subcultures of popular entertainment (41). Once film enters the cultural sphere, it is tied to these same binary rungs. I propose the Spectacle operates from a cultural sphere outside the boundaries of “high” or “low.” Studying its media texts allows one to see the language used to sell or attract viewers to film screenings and to examine the distinctive strategies the Spectacle uses to establish its unique programming sensibility.

Within the limited scholarship of exhibition studies, there exists even less work on microcinemas and other alternative exhibitive spaces. Brett Kashmere constructs a timeline illustrating that small, intimate, DIY screening spaces are present in exhibition history from the start, operating alongside dominant screening spaces in the United States. Kyle Conway uses a Canadian microcinema, Kino, as a case study to consider its multi-role as producer, exhibitor, and distributor, in the global network of microcinemas. Donna de Ville’s work incorporates a cultural ethnographic approach to present the transient but persistent nature of microcinemas. Although de Ville incorporates several New York City venues, the Spectacle Theater is not studied, and despite its founding in 2010, there exists no scholarship on this alternative theatrical site.

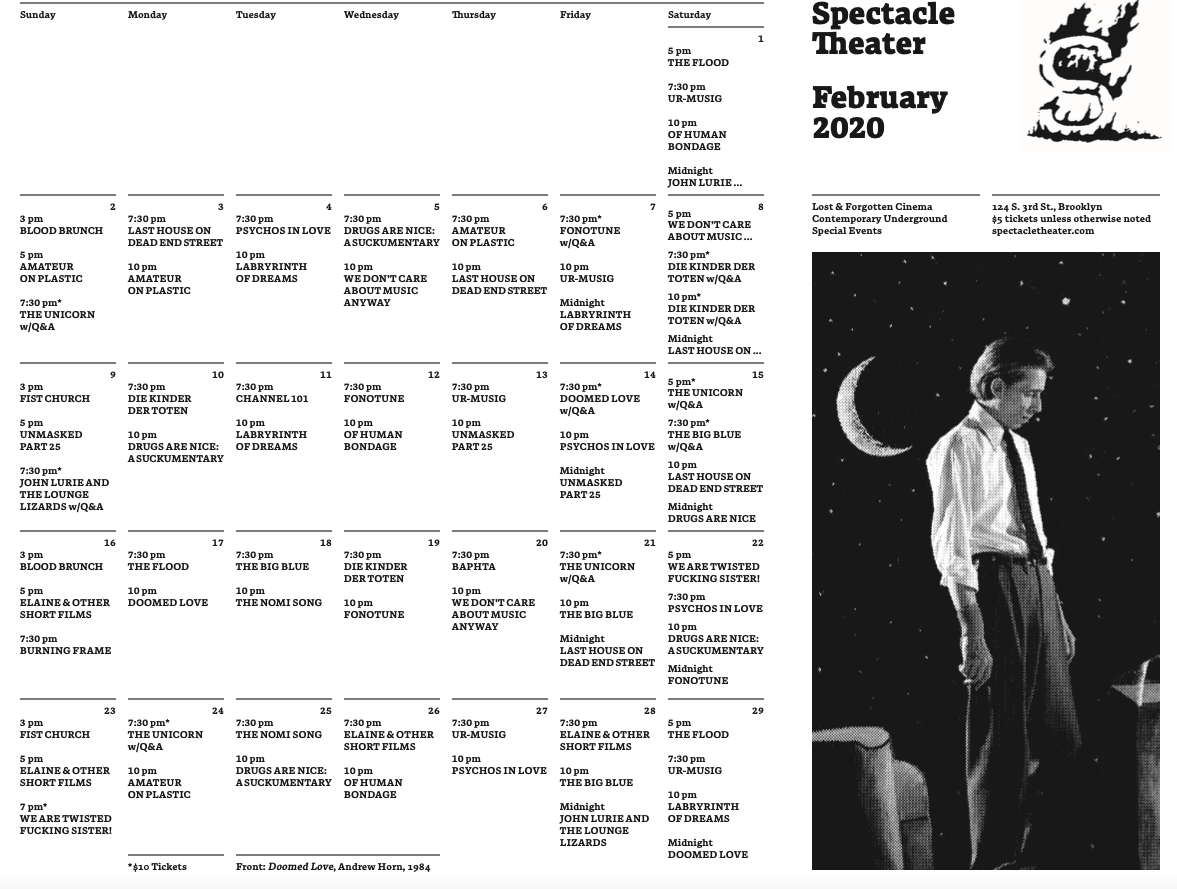

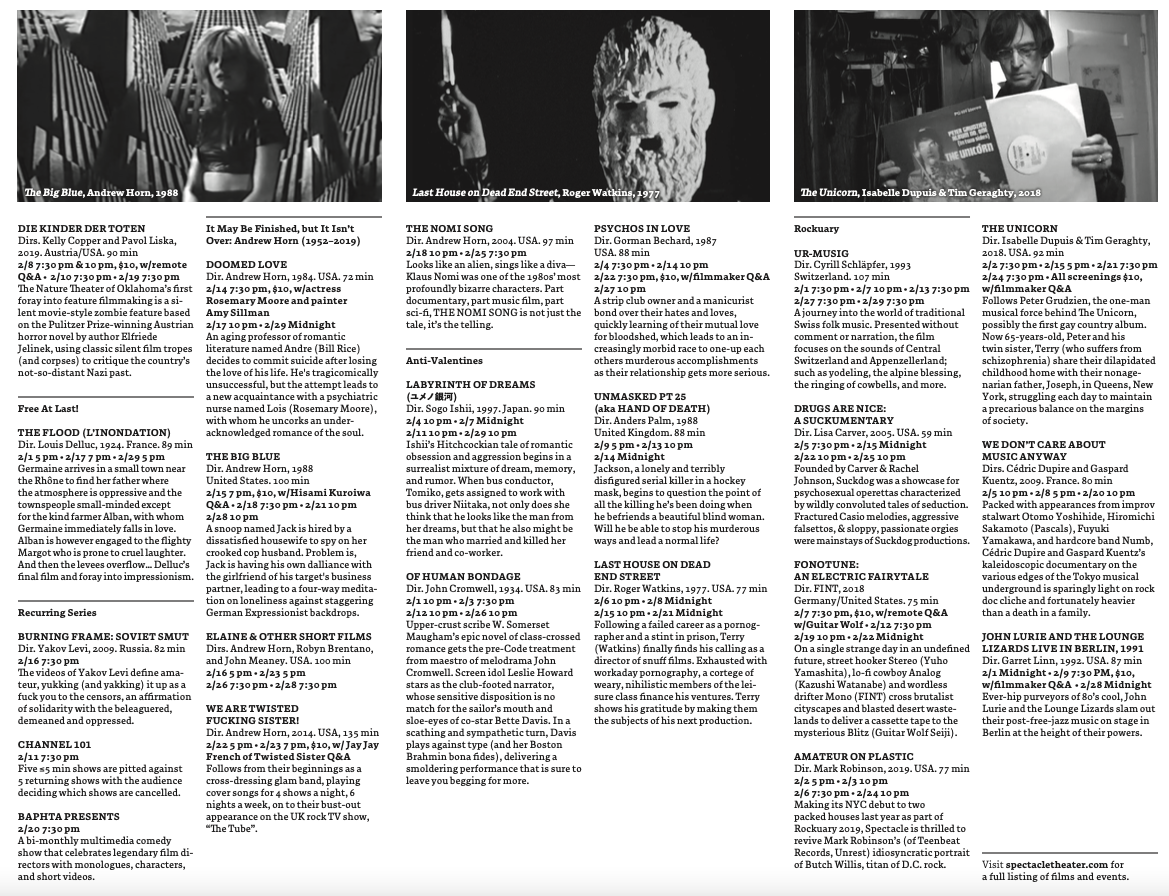

Examining February 2020 from the Spectacle’s pre-pandemic calendar displays a compilation of screenings culled from various curated series, all of which fall into one of the theater’s self-descriptors “Lost & Forgotten Cinema, Contemporary Underground, Special Events” (Macfarlane Re: Spectacle). As one example, Gorman Bechard’s Psychos in Love (1987) screens at 10 p.m. on Valentine’s Day as part of the Anti-Valentines series. The program describes the film as, “A strip club owner and a manicurist bond over their hates and loves, quickly learning of their mutual love for bloodshed, which leads to an increasingly morbid race to one-up each others murderous accomplishments as their relationship gets more serious [sic]” (Macfarlane Re: Spectacle). The description begins as a standard romantically toned film summary might, yet soon melds into a twisted description of two people bonded by bloodshed. The film’s conflict teeters on horror and farce, as next outlined in discourse of the lovers’ “morbid race” to be the winner with the highest body count as their relationship progresses.

Similarly, the trailer emulates this multi-tone balance of sweetness blended with terror as an upbeat song “Psycho in Love” plays during cuts to various scenes of the couple killing others, while also sitting side-by-side reading in bed (Spectacle Theater “PSYCHOS” vimeo.com). Text placed onscreen in the opening seemingly alludes to a line in the film referencing a communal hatred of grapes. The trailer ends with a dismembered head on a platter with the Spectacle staff-placed white cursive script “Anti-Valentine’s February 2020” over it. Intrigue for the screening is cemented through the originally produced promotional materials.

To promote the series on Twitter, the Spectacle tweets on February 11, 2020, “I can’t stand grapes I loathe grapes! All kinds of grapes! I hate purple grapes! I hate green grapes! I hate grapes with seeds! (@SpectacleNYC “I can’t stand grapes!)” The tweet contains a link to the trailer and news of a repeat screening on February 22nd featuring the filmmaker for a Q&A. The film’s title in all caps is accompanied by both heart and “crazy-eye” emojis placed on either side of the text. The linkage of the grapes reference from the trailer to the tweet when considered alongside the textual elements is again, a distinct choice linked to several ideas: The bond between the two film protagonists, the obsessive nature of the protagonists to profess such strong feelings over a type of fruit, and an illustration of the tonal tension between the sweet frivolity and obscene murderous actions of the two lovers. The Spectacle staff staunchly places the film in an “anti” positioning to the traditional concept and engagement with “love” on Valentine’s Day—evident from its late-night 10 p.m. screening slot, series title, and its darkly playful language and textual imagery in its promotional materials.

The Spectacle’s discourse in its paratexts represents a clear attempt to present media that is “anti” or “counter” to traditional Hallmark presentations of Valentine’s Day. Language in its program notes, trailers produced in house, and promotional tweets illustrates distinct promotional strategies to screen the forgotten, underseen, misunderstood, and boundary-less cinematic works. The combination of language used across these paratexts articulates the programmers’ impetus to remain playful but inviting with their promotions of these films, in addition to presenting films to the public that cannot be easily defined.

This cursory analysis of Spectacle Theater’s paratexts illuminates key observations pointing to other dimensions of useful study specific to the microcinema. The collective non-hierarchal programming structure of the space allows for creativity and agency in writing original program text and cutting in-house produced trailers and promotional language on Twitter. Future interviews with current and past collective members would provide additional context of how this language is formed and shared with the public, as well as illuminate decisions in curation. My framework here is limited and does not consider race, class, and gender, among other demographics, of the individual programmers comprising the collective. This information is key to consider in relation to the unpaid element of volunteer work. While volunteering and participating in a cinema collective is an empowering non-hierarchal organizational structure, its workers must be analyzed to understand the socioeconomic identities of the decision makers.

In a time of curated streaming sites, the domination of programming slots in arthouse theaters by major film distributor fare (Hatch Filmmakermagazine.com), and the coronavirus pandemic drastically impeding the stable future of cinematic spaces, the study of alternative exhibition sites is ever more pressing to contend with this rapidly changing exhibition field. Solace is found by the presence of these spaces since the birth of cinema, but their transitory nature calls for documentation of as many of these sites and their practices as possible.

Image Credits:

- The Spectacle Theater space. (Spectacle Theater website)

- Another shot of the Spectacle’s space. (Spectacle Theater website)

- The Spectacle Theater’s trailer for Psychos in Love (Gorman Bechard, 1987) via Vimeo.

- The Spectacle Theater’s tweet about the Psychos in Love screening (author’s screen grab)

- The Spectacle Theater’s February 2020 Calendar. (author’s screen grabs from email correspondence with film programmer Steve MacFarlane)

“About.” Spectacle, spectacletheater.com/about/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

Conway, Kyle. “Small Media, Global Media: Kino and the Microcinema Movement.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 60, no. 3-4, 2011, pp. 60-71.

de Ville, Donna. “The Persistent Transience of Microcinema (in the United States and Canada).” Film History, vol. 27, no. 3, 2015, pp. 104-136.

Hatch, Eric Allen. “Why I Am Hopeful: Programmer Eric Allen Hatch on the Future of Arthouse Programming.” Filmmaker Magazine, 11 Jun. 2018, filmmakermagazine.com/105446-why-i-am-hopeful/#.X0k-Wi2ZPfa. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

Kashmere, Brett. “A Subjective Chronicle of Microcinema Exhibition.” Moving Image Review & Art Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, Intellect, 2014, pp. 54–71, doi:10.1386/miraj.3.1.54_7.

Macfarlane, Steve. “Burn, Williamsburg, Burn: A Tribute, on the Occasion of Their Crowdfunding Campaign, to the Spectacle Theater.” Brooklyn Magazine, 30 Oct. 2015, bkmag.com/2015/10/30/burn-williamsburg-burn-a-tribute-on-the-occasion-of-their-crowdfunding-campaign-to-the-spectacle-theater/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

—. “Re: Spectacle Theater Programming – student request. Received by Kate Rogers, 30 Mar. 2021.

Rapold, Nicolas. “Long Live the Microcinema.” The Current, The Criterion Collection, 13 Jan. 2021, criterion.com/current/posts/7237-long-live-the-microcinema. Accessed 13 Jan. 2021.

@ SpectacleNYC. “I can’t stand grapes! I loathe grapes! All kinds of grapes! I hate purple grapes! I hate green grapes! I hate grapes with seeds!” Screening SAT FEB 22 @7:30pm with filmmaker Gorman Bechard for A+A…PSYCHOS IN LOVE (1987).” Twitter, 11 Feb. 2020, twitter.com/SpectacleNYC/status/1227345945546895360.

Spectacle Theater. “PSYCHOS IN LOVE (Dir. Gorman Bechard, 1987).” Vimeo, vimeo.com/385825437. Accessed 14 Apr. 2021.

Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, revised edition, Oxford University Press, 1976/1985, pp. 87-93.

Oh, it should be resolved soon.

I love to see blogs that understand the value of providing quality resources for free.