A Meta-Media Studies Approach to Digital Pedagogy

Victoria Grace Walden / University of Sussex

I currently have two roles at my institution: I am a senior lecturer in media studies and a Director of Student Experience. In the former role, I am currently teaching about (mostly digital) media through digital media (or ‘edtech’) and in the latter role, I am complicit in using the institution’s digital platforms to monitor attendance. Of course, there are valid reasons for such surveillance related to student well-being, however the amount of data I can see on any individual student’s engagement with our Canvas site (our VLE) and the duration of their time in a Zoom session feels invasive, particularly when we know many students are in complex and sometimes unsafe living environments. Furthermore, there are legal ramifications for those on Tier 4 Visas, whose attendance we have to report to the Home Office.

The friction that emerged between my two positions drew attention to a need to heighten our students’ critical digital faculties. That is not to say that they simply need digital literacies training. As David Buckingham[1] has well highlighted, ‘media literacy’ can become a neo-liberal tool which puts the responsibility on the individual and is often pushed by Governments who simultaneously try to attack ‘media studies’ (which, he argues, is a far better way to develop people’s understanding of the media).

Inspired by the work of Critical Digital Pedagogy[2], I went into this term with a critical perspective to the digital technologies I adopted in my teaching. Nonetheless, it seemed to me that whilst Critical Digital Pedagogy is heavily influenced by important Cultural Studies thinkers, notably bell hooks; there is less involvement in the field by media studies specialists. I call the approach I have trialled this term ‘Meta-Media Studies’. In this short commentary, I discuss two lessons in which simultaneously thinking and teaching critically with and about edtech opened up learning opportunities in which the technology we use in educational spaces became foregrounded as media we can and should study. The first is the use of Google’s 360 Tour platform for a Globalisation lecture with foundation year students. The second is the discussion of Canvas and Zoom in a MA seminar on Foucault and Surveillance Culture.

Globalisation on Google’s Terms: No Image of that Part of the World is Available, Please Select A Different Location

I started the term with my foundation year students by taking them on a ‘world tour’ in order to explore issues related to globalisation. In many ways, Google’s 360 Tour platform offered a great alternative to ‘death by PowerPoint’ because it allowed me to simply drop slides or images onto locations throughout the world. Several students remarked in the chat that this was the most travelling they had done in ages (I presented the tour through Zoom, so students could hear me speaking live and we could converse simultaneously). As I dropped my pin on the Google Map, however, I had to select which of Google’s photogrammetry representations of any particular location I wanted to use as my backdrop. I started on campus, highlighting the office and teaching spaces that I dearly missed. However, already I realised I was emphasising particular assumptions about where learning happens—the institution of the University.

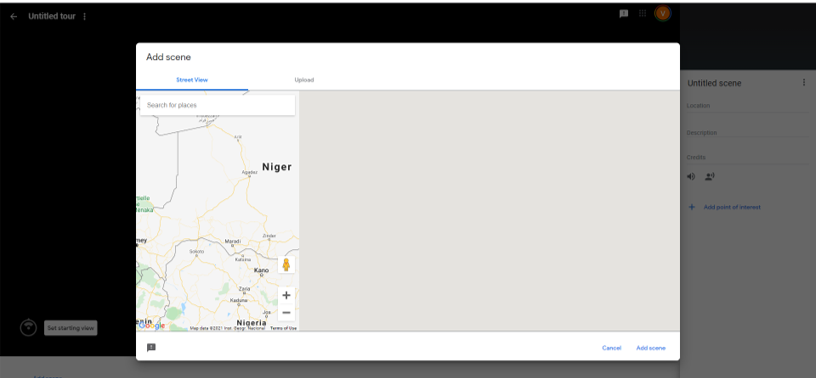

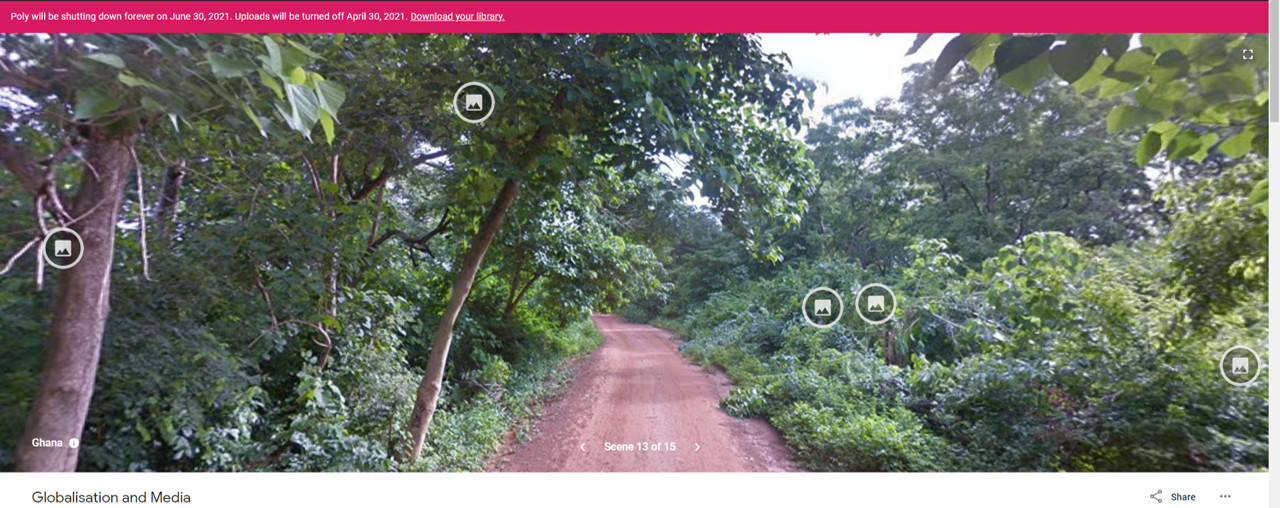

Some of the places I selected for the tour had personal meaning to me. I selected Marrakech, for example, to speak about the cultural differences in McDonalds’ menus across the world because it was one of the last places that I had seen a McDonalds beyond my own neighbourhood. At this point, a student started sharing in the chat their experience of growing up in the Moroccan city and a multitude of examples of cultural blending there. One of the examples that I wanted to discuss, however, was the power dynamics related to image-making in the former French West African colonies and the participatory practices of Jean Rouch. I had decided to ‘take the students’ to Niger, where Rouch had worked extensively. However, every time I tried to drop my map pin, it would not reveal an image. I soon realised that a large swathe of Northern and Central Africa was greyed out—unavailable for representation on this platform. So, I reluctantly chose the nearest country and location I could get a map pin to drop on, which happened to be a forest dirt track in Ghana.

This became a teachable moment and a space for discussion: what sites did Google consider worthy of capturing? To what extent is it really a 360 platform if it cannot capture the full 360 degrees of the world? I was able to go under the sea (to discuss the materiality of Internet cables), but I could not go to a widely inhabited area of the African continent. In the chat, this ignited decolonisation discussions in ways I had not previously experienced in week 1 of a foundation year programme. The edtech platform through which I was teaching became our case study for doing media studies.

You Don’t Need Your Camera On—I Can Still ‘See’ You: Surveilled Students

One of the topics of an MA core module on which I teach called ‘Media, Communication and Culture’ is Surveillance Culture. In this week, we introduce students to Foucault, but also explore a multitude of more contemporary academic texts particularly related to digital surveillance. Coincidently, we explored this topic in the same week as we were doing a major attendance review. Taking registers during remote teaching is challenging. Some students cannot join synchronously, so it would be unfair to simply take Zoom attendance as the only data. Therefore, there was a policy to check Canvas engagement too—how long did a student stay on the site? What did they click on? The debates we were having as teaching teams about ‘what constitutes student engagement?’ for me echoed the long-standing discussions in media studies about ‘what constitutes interactivity/participation?’ which have been at the forefront of questioning the extent to which so-called ‘new media’ is really new.

We had already discussed recommendation algorithms on the module; thus, it was no surprise that the students quickly turned to this example to consider the power dynamics at play in surveillance cultures. However, as is often the case, they were initially stuck in the dichotomy of ‘big bad corporations’ versus ‘unknowing, innocent users’. I was trying to get them to think about their own complicity in acts of surveillance, but my suggestive questions were not working. So, I asked them to what extent my role as their tutor involved surveillance. They acknowledged that I could see them on Zoom (as most of the class had their cameras on) but did not record it so they could speak freely in the seminar space. I then realised how little they were aware of Mark Andrejevic’s notion of passive interactivity[3] and introduced this term whilst listing the durations that some students had spent in a different Zoom session (anonymised of course!). Then I went on Canvas and identified how many times different students had clicked on a specific resource. The students arose in outrage: they were not aware of how much their online movements could be monitored. I highlighted that the University policy was available to them on the home page of our internal website via a hyperlink (of course, few knew this was there). We had an hour discussion about datafication, biopolitics, participation, surveillance, and power, through this case study.

These experiences emphasised to me that we do not interrogate the technologies—digital or otherwise—that we use to encourage students’ learning enough, during preparation or in class. Thus, we continue to be complicit and non-transparent about the power dynamics at play in educational culture whilst paradoxically critiquing those elsewhere. A Meta-Media Studies approach to digital pedagogy insists on being a proactive yet critical adopter of edtech. We cannot really understand the power dynamics of these technologies and platforms if we do not use them; nevertheless, in bringing them into our teaching we must be critical at every stage: from researching the platforms we use, to planning our pedagogy through them and how we introduce them to students.[4]

Image Credits:

- Teaching and learning are increasingly reliant on computers and tech devices. Victoria Grace Walden suggests a ‘meta-media studies’ approach to critically examine the ways we use technologies to teach with and about media. Photo by Marvin Meyer from Unsplash.

- Two images from Google Tour: The first illustrating what happens when I tried to drop my map pin near cities in Niger. The second is the nearest place I was able to drop my pin. (Both images are the author’s screenshots)

- An extract of the types of data Canvas collects on individual students. Student names are listed below in rows, and I can ‘click’ on each student to investigate further. (Author’s screenshot)

- Buckingham has written about the tension between ‘digital literacy’ and ‘media education’ in many contexts. Three examples include: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2304/rcie.2007.2.1.43 , https://davidbuckingham.net/2019/04/30/who-needs-digital-literacy/ and his most recent book The Media Education Manifesto. [↩]

- For those interested, the Hybrid Pedagogy Journal is a good place to start exploring ‘Critical Digital Pedagogy’: https://hybridpedagogy.org/. [↩]

- Andrejevic, M. (2016) ‘The Pacification of Interactivity’. In: D. Barney et al. (eds) The Participatory Condition in the Digital Age, pp. 187-206. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. For more sources related to interactivity/ participatory cultures debates in media studies, see my reading list: https://digitalholocaustmemory.wordpress.com/2020/07/10/reading-about-digital-holocaust-memory/. [↩]

- Some of the issues raised in this piece were part of my presentation at the international online conference I organised on February 13th 2021: ‘Teachers Talking: What Could Media Studies Be? Media Education from Primary to Higher Education’. The conference recordings are available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCP9F0XXDcY&list=PLd2yOEItgvC1NGvxgm_0rOYopBzD7IEE8&index=26&ab_channel=VictoriaWalden. The conference was designed as a conversation starter, any reader interested in joining a network dedicated to debate and action related to Media Education Futures is invited to contact the author at v.walden@sussex.ac.uk. [↩]