Streaming Egypt: Netflix & the Transnational Flow of Egyptian Media

Hazem Fahmy / University of Texas at Austin

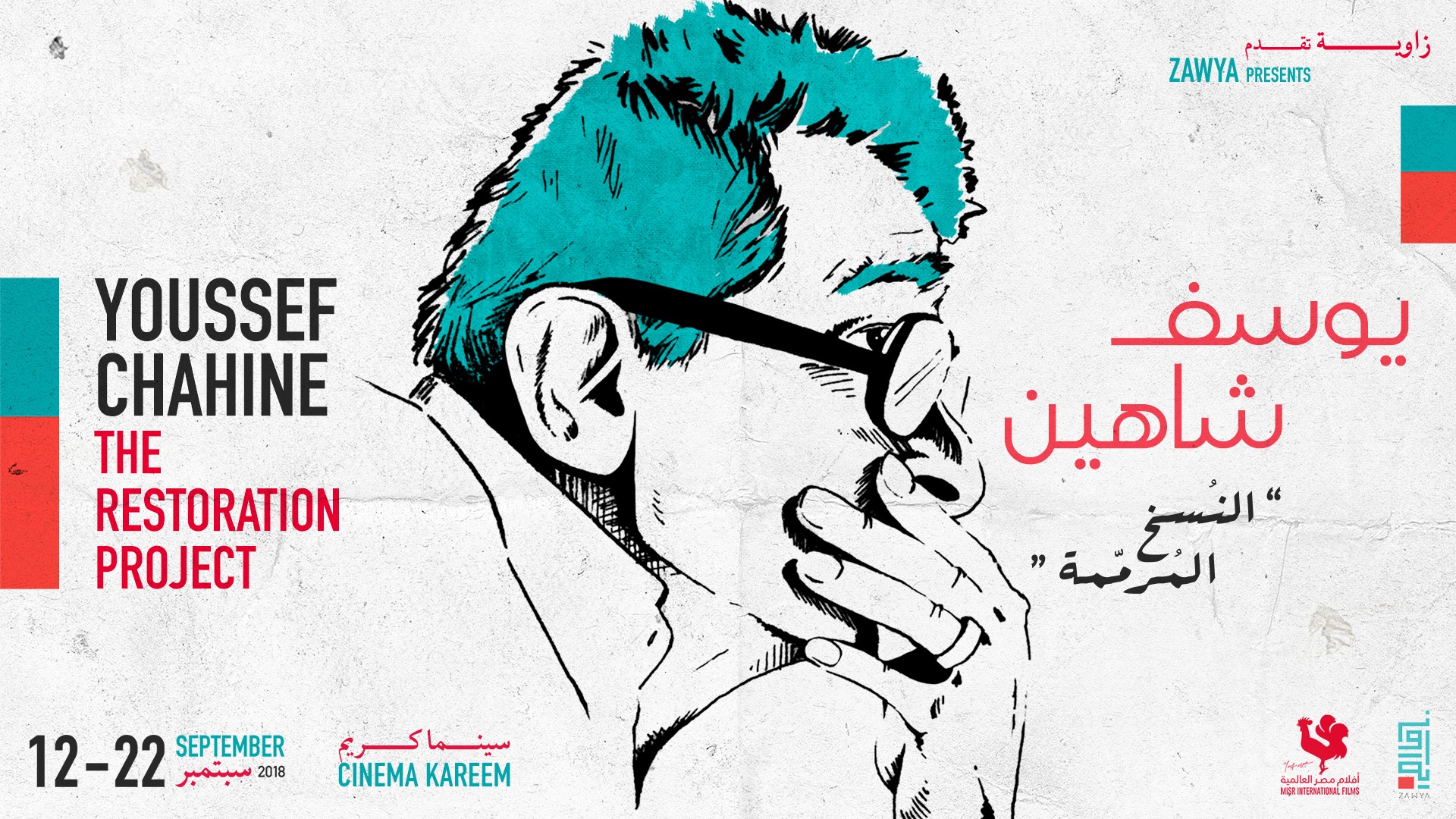

In the late summer of 2018, Cairo’s premiere arthouse cinema, Zawya, announced that it would screen twenty of the late Youssef Chahine’s films throughout that September. Zawya had screened Chahine’s films before, for example in 2014, but this retrospective would distinguish itself by screening the recently restored versions of these films as part of a project that had been spearheaded by Misr International Films––a film production and distribution company that was founded by Chahine himself––in collaboration with several European partners.

To my misfortune, I had already left the country to begin my graduate studies in the States when the announcement had been made, so I could not catch any of the Zawya screenings. This was bitterly disappointing as I had only seen low-quality versions of Chahine’s films, mostly on YouTube, and I was terribly excited by the prospect of seeing them restored on a big screen with an audience. Every now and then, I would check in on the tours of the restoration project throughout Europe and the Middle East, wondering when, if ever, the films would make their way across North American screens. Astonishingly, the freshly restored work of this Cannes-favorite Egyptian auteur first became available to me in the States neither through a cinematheque nor a festival, but rather through Netflix’s June 2020 slate.[1]

For anyone who had been following Netflix’s steady acquisition of Egyptian and Arab media content over the last two years, the announcement of Chahine’s arrival onto the platform seemed ostensibly perplexing yet ultimately inevitable. This process started in April of 2018 with the announcement that Grand Hotel,[2] the 2016 Egyptian remake of the 2011 Spanish series of the same name, was to be the first Egyptian series on Netflix. This prompted several positive responses from anglophone Egyptian outlets, many of which argued that the inclusion of Egyptian media, especially a series that had been as locally lauded as Grand Hotel, on the global platform that Netflix had become, was a tangible benefit for the Egyptian media industry.[3]

Over the coming months, Netflix would continue to add Egyptian films and television series to the platform. Though they encompassed a wide variety of genres, the criteria otherwise seemed fairly consistent for most of the succeeding two years: mainstream, popular works that were overwhelmingly produced in the 2010s. There were, of course, exceptions here and there––one of the most notable being Abu Bakr Shawky’s 2018 festival favorite Yommedine––but the vast majority of added titles, particularly the television series, adhered to the production value, initial local success[4], and star power of Grand Hotel.

Netflix’s approach to acquiring Egyptian media did not significantly change until April of this year, when it was announced that the company was to bring the previously televised recordings of several iconic Egyptian comedy plays[5] to the platform. Though the selected plays, particularly The School of Mischief (Mustafa, 1973) and No Longer Kids (Asfory, 1979), are easily some of the most recognizable works in mainstream Egyptian media, this was a sharp departure from Netflix’s previous pattern of prioritizing works from the 2010s. Prior to the acquisition of the plays, there were maybe a handful of films from the 2000s, but following their arrival the platform now had several highly notable Egyptian works from the 1970s and 80s. A little over a month later, it was announced that a wide selection of Chahine’s films, stretching from his earlier films produced within the Egyptian studio system to his later financially independent and aesthetically transgressive work, would also be available on the platform. Similarly to the arrival of Grand Hotel, the debut of Chahine’s films was swiftly celebrated across online Egyptian and Arab publications, many of which took the opportunity to reflect on his life and work, as well as reiterate his significance to the history of Egyptian cinema.[6]

Though the Egyptian titles now available barely scratch the surface of the country’s film, television and/or media landscapes, they do present a strikingly eclectic sample size that is unparalleled in any shape or form on any other American streaming service. As early as it is to tell which direction the company will go in next in terms of its focus on Egypt and/or the Arab world, there is no doubt that Netflix’s recent intensive acquisition of diverse classical Egyptian content presents a significant shift from its aforementioned narrow focus on popular, mainstream film and television from the 2010s.

Given the increasing popularity of Netflix in Egypt,[7] this shift is not necessarily surprising. As Ramon Lobato has argued in his book, Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution, the company has spent the last few years seeking to localize its platform across the plethora of different national and/or linguistic markets in which it has been trying to entrench itself. Comparing Netflix’s process of internationalization to that of MTV two decades earlier, Lobato states that the company’s eventual “dawning realization that what works at home does not always work abroad” has spearheaded its “commitment to localization and local content production.”[8] As with any critical discussion of global television and media flows, this inevitably raises questions of cultural imperialism and to what degree can Netflix’s involvement in Egyptian and/or Arabic media be located within larger patterns of American hegemonic influence over global media.

But before discussing the political and/or cultural significance of Netflix’s acquisition of Egyptian content, we must first understand the role Netflix plays within the Egyptian and/or Arab streaming landscape. For all of its vast infrastructure and resources, Netflix has by no means dominated the Egyptian streaming market. Given the stiff competition posed by local and regional agents, it is thus not useful to reduce the company’s involvement in Egyptian media to an essentialist category of “cultural imperialism.” This is, of course, not to suggest that the company’s relationship with Egyptian media structures is remotely equitable, merely that it is unhelpful to think of that relationship solely through that lens. As Lobato states: “the challenge of explaining international television flows is not so much about picking one paradigm over another […] but rather about making careful distinctions between distribution and reception, economic structure and audience/buyer agency, and the more specific dynamics of various program types.”[9] This final category is by far the most pertinent to this article’s interest in the significance of the emergence of Egyptian media content on a platform such as Netflix’s.

While Netflix may be the most successful American streaming service available in Egypt, it is not without fierce local and regional competitors; the two most notable being the streaming channels of the Emirati-based cable giants Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC) and Orbit Showtime Network (OSN).[10] Both offer far more Egyptian and Arabic content than Netflix, including some of Chahine’s restored films. The former has produced several original Egyptian series whereas the latter stands to rival Netflix’s slate of American content given that its partnerships with other giant American streamers such Disney+, HBO and Hulu[11] allows it to stream many of their high-profile original and licensed content exclusively throughout the Middle East.

However, unlike Netflix, these services are not aimed at a general global audience. MBC’s service, Shahid VIP, is available internationally, but is first and foremost dedicated to Arabic-language media and Arabic-speaking audiences. The vast majority of its content, for example, is not supported by English subtitles. OSN, on the other hand, is not even available outside of the Middle East. As such, more so than affecting the streaming landscape within Egypt or the region, Netflix’s acquisition of Egyptian content, while certainly advantageous to Egyptian subscribers either locally or abroad, is actually most significant for viewers who are not fluent in Egyptian Arabic, for whom Netflix now provides a slate of diverse Egyptian content in high video quality and, most importantly, with English subtitles.

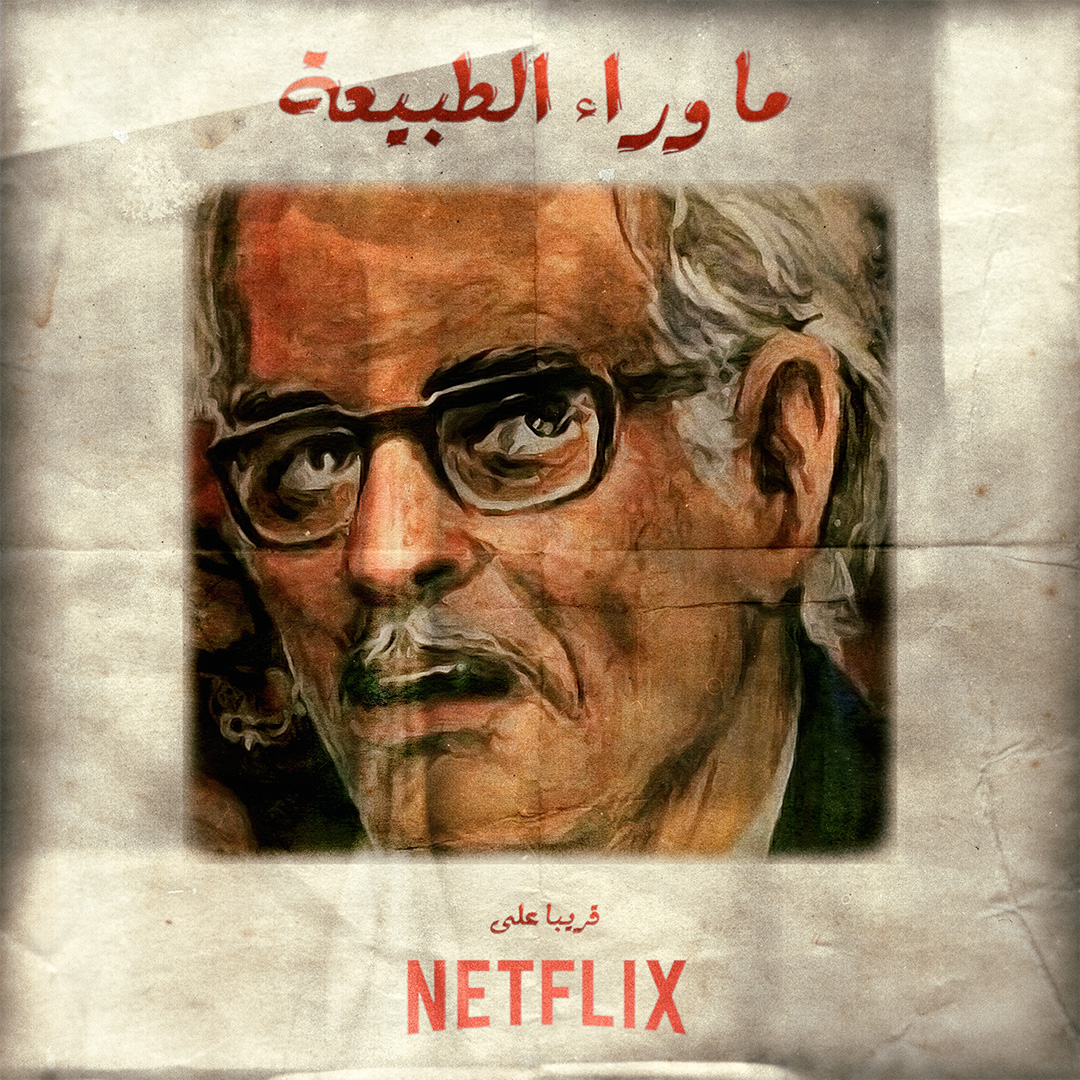

Netflix’s relationship with Egyptian media is nowhere near set in stone just yet. In fact, a mere few hours into the writing of this essay, it was announced that the company’s first Egyptian original series, The Paranormal[12], has just wrapped up its filming. As of yet, Netflix’s acquisition of Egyptian media content over the last two years has not conformed to the common assumption of the “one-way street”[13] of global media flows, but has represented a rare case in which an American media company’s involvement in another country’s film and television infrastructure has had a much more significant impact on the platform itself than the country in question. This could certainly change should Netflix pick up its original Egyptian film and/or television production over the next decade, but for now it is safe to say that, when it comes to Netflix and Egyptian media, the flow––while by no means equal––has been back and forth.

Image Credits:

- 1. A poster for Zawya’s 2018 Youssef Chahine Retrospective

- 2. A still of Shahid VIP’s dashboard interface

- 3. A teaser poster for Netflix’s upcoming original Egyptian series, “The Paranormal”

- “Youssef Chahine’s Films Are Coming to Netflix this Month.” Scene Arabia. June 05, 2020. https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/48794/1/100-gecs-laura-les-dylan-brady-minecraft-charli-xcx. [↩]

- Renamed Secret of the Nile on Netflix.. [↩]

- “’Grand Hotel’ Just Became The First Egyptian Series On Netflix.” Nile FM. April 12, 2018. https://nilefm.com/entertainment/article/1235/egyptian-series-the-grand-hotel-featured-on-streaming-service-netflix. [↩]

- The contemporary Egyptian films on Netflix, while generally popular and commercially lucrative, have generally received far less critical acclaim than the series, which is hardly surprising given how popular Egyptian television has fared significantly better than cinema with critics over the last decade. [↩]

- “Our Favorite Classic Egyptian Plays Are Coming to Netflix Just in Time for Eid.” Scene Arabia. April 30, 2020. https://scenearabia.com/Culture/Our-Favourite-Classic-Egyptian-Plays-Are-Coming-to-Netflix-Just-In-Time-for-Eid?M=True#:~:text=This%20May%2C%20Netflix%20MENA%20is,the%20true%20dynamic%20duo%20that. [↩]

- [1] “Films by Egypt’s famed director Youssef Chahine released on Netflix.” Ahram Online. June 18, 2020. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/5/32/372419/Arts–Culture/Film/Films-by-Egypts-famed-director-Youssef-Chahine-rel.aspx. [↩]

- As the company, notoriously, refused to publish any kind of data on user’s consumption of its service, reliable and accurate information regarding Egyptians’ usage of Netflix is hard to come by. That said, it is safe to say that a steadily improving internet infrastructure, paired with the increasing ubiquity of smart televisions, has made Netflix a far more accessible and practical service in Egypt than when it launched in 2016. [↩]

- Lobato, Ramon. Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution. New York: New York University Press, 2019, 109. [↩]

- Ibid, 143-144. [↩]

- MBC’s service initially launched as Shahid (Arabic for “watch”) and was rebranded this year as Shahid VIP whereas OSN’s service initially launched as Wavo and was rebranded this year simply as OSN. [↩]

- Nair, Manoj. “OSN now has the force to take on Netflix, Amazon Prime in streaming TV services.” Gulf News. May 22, 2020. https://gulfnews.com/business/osn-now-has-the-force-to-take-on-netflix-amazon-prime-in-streaming-tv-services-1.1590130700444. [↩]

- “Netflix’s first original Egyptian movie is ready.” Egypt Independent. July 18, 2020. https://www.egyptindependent.com/netflixs-first-original-egyptian-movie-is-ready/. [↩]

- Nordenstreng, Kaarle & Vairs, Tapio. “Television Traffic–a One-way Street?: A Survey and Analysis of the International Flow of Television Programme Material.” Reports and Papers on Mass Communication, vol. 70. New York: UNESCO, 1974, 11. [↩]