“Maybe You Don’t Know How to Listen…”: An Exercise in Contextualization

Laura Brown / University of Texas at Austin

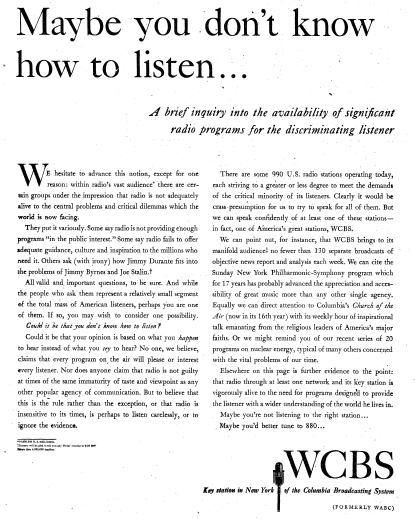

On November 3, 1946, WCBS—the flagship radio station of the Columbia Broadcasting System—ran a full-page advertisement with “Maybe you don’t know how to listen…” splashed across the top in an eye-catchingly large font. Almost 74 years later, as I was skimming through the pages of The New York Times for another research project, the advertisement again caught an unsuspecting reader’s attention. A full-page, wordy advertisement for a radio station that conveys a sentiment of “it’s not us, it’s you” was more than enough to pique my curiosity of what possibly could have made WCBS run such an ad.

The advertisement starts with the acknowledgment of recent, unspecified criticisms concerning radio’s inability to provide programming that “offer[s] adequate guidance, culture and inspiration to the millions that need it.”[1] However, the copy makes a slightly stand-offish turn by asking the reader if “your opinion is based on what you happen to hear instead of what you try to hear,” and postulating that a listener’s perception of radio being a medium that “is insensitive to its times” is a result of “listen[ing] carelessly, or [ignoring] the evidence.”[2] The advertisement includes a slew of programs that it considers buck the described criticism, and ends with suggesting that the listener ultimately is “not listening to the right station,” and should instead tune to 880, WCBS.[3]

I have turned to a bit of scholarship on advertisements (specifically, broadcasting-related advertisements) in an attempt to provide myself with an academic lens that could guide not just my analysis of this advertisement, but perhaps even help shed some light on the types of sources I could refer to during my quest for contextualization and understanding. Both Michele Hilmes and Cynthia B. Meyers have discussed the (often understatedly) massive role advertising agencies played during radio’s hey-day of the 1930s and 1940s, which essentially boils down to advertisers controlling a program, practically from soup to nuts.[4] As Meyers notes, this advertiser dominance within radio did not last forever. Around the time the advertisement in question was run (late 1946), the commercialism of and the advertiser’s place in radio was being reconsidered by networks, the US government, social scientists, and critics.[5] Each of these groups had their own incentives for and reasoning behind this “revolt,” as Meyers calls it, but one common thread is the notion of programming for public service.[6] From here, I’ve established a baseline for search for historical context. This advertisement clearly was not run out of the blue; it potentially could be a reaction to larger conversations surrounding commercialism and public service broadcasting, and Meyers has given me a few prime suspects I can look into as giving WCBS possible motive to push back against.

Locating (a bit of) Historical Context and Early Ruminations

As Meyers and others have noted, the post-war period of American radio was marked by a new (or, for some, renewed) prioritization of public service programming, which led to a number of groups to call for a rehabilitation of radio. The most high-profile of these crusades to reform radio was the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) Public Service Responsibility of Broadcast Licensees, more commonly known as “the Blue Book.” While the specifics and ultimate efficacy of the Blue Book can be discussed and debated in another forum, for my purpose, its mere existence as the product of a government-adjacent agency pushing for broadcasters to program in the “public interest, convenience, and necessity,” or else face possible issues when it came time to renew their broadcasting licenses, is noteworthy enough. With the FCC’s Blue Book making news headlines both in trade and popular press, it’s decently evident that this ad, which includes the phrase “‘in the public interest,’” is at least somewhat in response to the conversations surrounding public service programming.

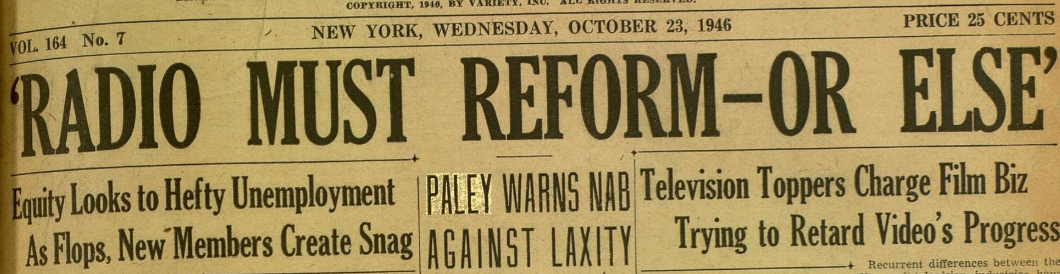

Turning towards the industry, radio’s trade association, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), had their annual convention from October 21-24, 1946, just two weeks before the advertisement was published. At the conference, CBS chairman William S. Paley addressed the crowd with a speech that acknowledged the relative shortcomings of radio’s public service programming, and made a call-to-action for broadcasters to apply the same level of “ingenuity and imagination as we devote to entertainment shows.”[7] However, in the same speech, Paley acknowledged the criticism that was being lobbed at radio and called it justified, noting that only broadcasters themselves were to blame for its shortcomings.[8] Wait a minute….The advertisement—which was for WCBS, and touted itself as the “key station in New York of the Columbia Broadcasting System”—put the blame on listeners, not broadcasters….

In addition to looking at the actions, events, and conversations that could have led up to the advertisement’s publication, I think making note of the coverage of and reactions to the ad (or lack thereof) can also add some much-needed context. In doing a preliminary search through popular trade publications (Broadcasting, Variety, Sponsor, and Billboard) only one outlet—Broadcasting—made mention of the advertisement. Broadcasting’s coverage was in the form of a summary of the advertisement: making note that the advertisement was run, and that WCBS was putting blame on listeners. What does it mean that most publications made no mention of the ad? Was an ad for a New York City station not deemed important enough to be published in other national publications?

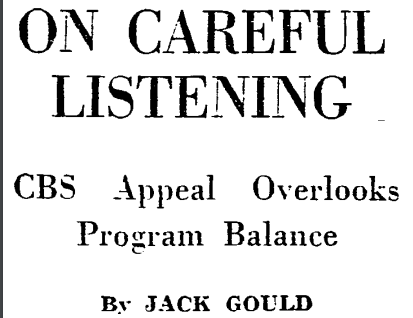

Moving along to popular press, I searched the columns of notable New York-based radio critics, Jack Gould (of The New York Times) and John Crosby (from The New York Herald Tribune). In my research, I found that the advertisement ran in both the Times and the Herald Tribune, yet only Gould made mention of it in his column (did Crosby not comment on the ad in his daily column because his column was syndicated beyond the New York area? Did he think it was beneath his station?). According to Gould, the ad is a reflection of “persuasive self-righteousness,” that exhibited “broadcasting’s traditional condescension toward the highbrows.”[9] Gould continued lambasting WCBS, noting that “more than 70 per cent [of the programs listed in the advertisement] fall within time periods which radio knows[sic] enjoy a minimum listening audience—Saturday afternoon, Sunday morning, early Sunday afternoon, or late in the evening, etc.,” and argued this scheduling of programs forced listeners with a “selective” taste live to a “monastic existence.”[10] Ultimately, Gould concluded that radio as a whole needs to provide a better program balance during the popular listening hours of 6pm to 11pm, as if they “are the most popular listening periods for the majority, they are just as popular for the minority,” and that “if the discriminating listener is to enjoy emancipation, the primary responsibility rests not on himself but on those who hold him in bondage.”[11] Inappropriate equivalencies to slavery aside, Gould’s column further expands our considerations of the advertisement: we can think about broadcasters’ schedules, taste cultures, and accessibility in our analysis and understanding of this ad, public service programming, and other matters of the time.

I’ll right off the bat say that by no means do I feel comfortable providing firm answers to the questions surrounding the intent, purpose, and idealized reception of this advertisement, simply because I did not have the time or (and perhaps more importantly) the resources to provide such answers. However, what I can provide is what I’m calling an “educated speculation.” From the preliminary research that I’ve done, all signs point to this advertisement being run as a means to rebuke the multitude of conversations that were being held around the over-commercialization of radio and the calls for more broadcasting in the public service. WCBS (or, perhaps, CBS more generally) wanted to separate themselves from the rest of the pack, and possibly felt that this display of “we have the programs you want, you just aren’t listening to them” was one way to draw a line in the sand.

But there are still so many questions left unanswered: Did the CBS network know about this advertisement? How were networks involved in the advertisements and marketing of their affiliates and owned-and-operated stations? Could this be part of a branding strategy for CBS radio (and was there even branding of US radio stations in the mid-1940s?), and if so, what was the brand CBS/WCBS were trying to cultivate? What about Paley’s speech putting blame on broadcasters—was this advertisement damage control? Was this ad only run in the New York City area, and if so, why? In addition to these questions, I’m sure there’s also many that I am not even thinking to ask. There are also other pieces of historical context that may have directly, indirectly, or not-at-all influenced this advertisement: the upcoming US presidential election (just a few days after the ad was published), WCBS recently changing their call letters from WABC, and CBS’ impending entry into television all could have something, everything, or absolutely nothing to do with this ad.

This short dive down a historical rabbit hole also isn’t just an exercise in contextualizing an advertisement. I view it also as a means to reconsider the ways in which I can use materials. Advertisements can be more than just paratextual or peripheral materials—they can also act as the focus of or launching pad for a project. I can turn to a critic’s work not just for a review of a program, but also commentary on a medium. Materials like advertisements, trade and popular press, critics’ columns, and conference proceedings are all multifunctional. While there will always be sources that I will not have access to (whether they don’t exist anymore, or perhaps never existed in the first place), this reconsideration and repurposing of materials that are available to us—especially during a time of quarantine—provides the potential to help flesh out a medium’s history from a micro- (and perhaps even macro-) level.

Image Credits:

- WCBS’ “Maybe you don’t know how to listen…” advertisement. (Author’s screengrab.) WCBS, “Maybe you don’t know how to listen…,” The New York Times, November 3, 1946, 97. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Variety’s coverage of William S. Paley’s speech at the 1946 NAB Convention. (Author’s screengrab.) Variety, October 23, 1946, 1. ProQuest.

- Broadcasting magazine’s report on the advertisement was more of a news briefing than commentary. (Author’s screengrab.) “Answers Criticism: Listener Not Always Right, Says WCBS,” Broadcasting, November 11, 1946, 59. WorldRadioHistory.com.

- New York Times radio critic Jack Gould used the advertisement as a means to attack CBS’s programming strategies. (Author’s screengrab.) The New York Times, November 17, 1946, 83. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- WCBS, “Maybe you don’t know how to listen…,” The New York Times, November 3, 1946, 97, ProQuest Historical Newspapers. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- See Michele Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting: From Radio to Cable (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 80-7 and Cynthia B. Meyers, A Word from Our Sponsor: Admen, Advertising, and the Golden Age of Radio (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014). [↩]

- Meyers, A Word From Our Sponsor, 255-8. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- “Paley’s Primer on Programming,” Variety, October 23, 1946, 90. ProQuest. [↩]

- George Rosen, “Paley Warns NAB Against Laxity,” Variety, October 23, 1946, 1. ProQuest. [↩]

- Jack Gould, “On Careful Listening: CBS Appeal Overlooks Program Balance,” The New York Times, November 17, 1946, 83. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]