Locating the Local in Late Night Television

Eric Forthun / University of Texas at Austin

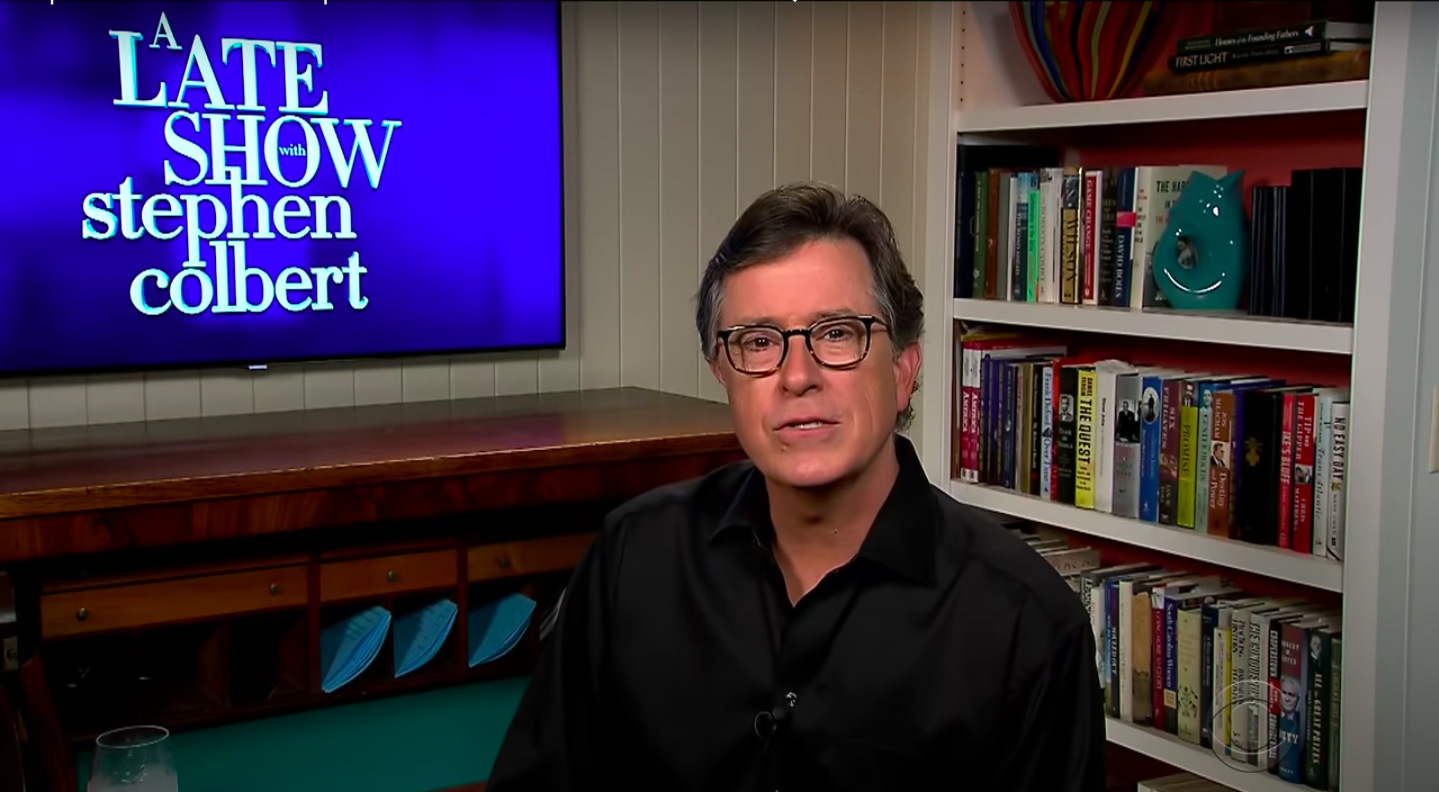

Most of our television series either look different or have disappeared off the air altogether in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic across the world. Late night television is no exception, with programs no longer recording in front of audiences or filmed on location with large crews. Now, hosts perform monologues in bedrooms or in front of white curtains to an audience of maybe one, resembling a YouTube vlog more so than a television production. The silence from an absent studio audience is both surreal but also essential, speaking to the unprecedented nature of this pandemic.

Late night hosts such as Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers, and Trevor Noah have shifted the tenor and scope of their programs almost entirely toward President Trump’s criminally negligent response to COVID-19, his militaristic targeting of peaceful protests outside of the White House, and his cruel and racist dismissal of the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and hundreds of other black Americans at the hands of police officers. On June 18th, even Jimmy Fallon popped into a Juneteenth BBQ hosted by the sketch comedy group Astronomy Club, where the group explained historical acts of racist violence as Fallon asked what he can do to help. The personal has always been political, but late night is now, more than ever, emphasizing that political action rather than humor is needed to address these issues.

Late night has often been understood as a broadly appealing genre that “reinforced the notion that political participation is pointless, parties and candidates are interchangeable, and democracy is futile.”[1] Now, however, late night appears to be tapping into a cultural zeitgeist that directly asks for social and cultural change, even if it primarily comes from white male voices at the helms of these shows. Late night programming no longer acts as the escape from reality that Johnny Carson once made it out to be, who once remarked with Barbara Walters that comedians can’t take themselves too seriously because The Tonight Show is made to “amuse people, to make them laugh.”

Maybe we need to re-imagine what late night’s cultural function is. The genre has effectively been siloed in only two locations—Los Angeles and New York City—since Tonight’s launch on New York affiliate WNBT in 1954. After Tonight’s move to NBC’s network feed, almost every major late night show has recorded in LA and NYC, with The Tonight Show famously moving between the two after Johnny Carson moved the series to LA in 1972 (because he preferred to be closer to movie stars) and Jimmy Fallon moved it back to NYC in 2014. One of the largest absences in how we understand late night is how local and regional late night production can tell us more about the late night talk show’s cultural and industrial significance, particularly as a means of de-centering the whiteness and maleness so thoroughly embedded in the genre. Access remains the foundational issue as late night’s devaluation over the years resulted in few available recordings of pre-Carson programming.

Late night has so thoroughly been a misogynistic space, one where whiteness, hegemonic masculinity, and heterosexuality arguably act as the genre’s defining characteristics since Steve Allen launched the Tonight show. There have been notable recent exceptions, such as Trevor Noah and most recently Lilly Singh, but there were lackluster attempts in the wake of David Letterman and Jon Stewart’s retirements to reform late night’s representational politics with little systemic change (a topic I covered in a 2018 Flow piece). W. Kamau Bell noted in a 2014 TV Guide interview that, across traditional television platforms, when a host “isn’t great right away—and this is what usually separates white guys from the rest of us—he’ll get a chance to work out the kinks and get it right.”

When we turn to local programming, we can critically assess the intermingling of identity and industry, particularly with local affiliates and their consistent influence on national media production. One of the first instances was in 1991, when The Tonight Show moved back from 11:30pm to 11:35pm to appease NBC affiliates across the country, as there were threats from 20 to 30 affiliates to drop coverage since they wanted to air syndicated re-runs of popular programs like Cheers because the affiliates made full advertising revenue from those (unlike Carson’s show). Most famously, affiliates in early 2010 pressured NBC to move Jay Leno back to the 11:35pm slot after The Jay Leno Show began to flounder in ratings at 10pm and continuously hurt local affiliates’ news ratings—the biggest source of revenue for most local affiliates.

Just recently, local NBC affiliates expressed concern over late night staples such as The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon and Late Night with Seth Meyers premiering early on NBCUniversal’s upcoming streaming service Peacock, as ratings will likely decline along with subsequent advertising revenue. A deal beneficial for both parties is needed, as Variety notes, since the network-affiliate relationship is so important that “Meyers in every broadcast features a coffee cup on his desk that nods to a specific NBC station.”

Understanding affiliates will prove helpful in re-situating late night’s industrial significance, but locating the late night talk show hosts outside of traditional media production will also enable us to re-evaluate the genre’s cultural meaning. Since much of late night television has focused on the individual agency of hosts, these histories have overwhelmingly perpetuated mythic “great white male” narratives that devalue and erase the contributions of marginalized groups. These histories have also valued national appeal and broadness as essential for success on late night programming, but there have been success stories elsewhere on local and regional late night productions.

The most significant success story was former pornographic actress Robin Byrd’s eponymous show in New York. Through a leased access deal with Manhattan Cable Television, The Robin Byrd Show ran for over thirty years while looking and sounding completely different from The Tonight Show and other late night attempts by broadcast networks. The show often featured other adult film entertainers, nudity, and discussions of taboo topics such as sex toys and dental dams, all in front of either a red backdrop or in more intimate settings like a bedroom. Byrd starts off each show by asking the audience to “lie back,” “get comfortable,” and “snuggle up next to your loved ones. And if you don’t have a loved one, you always have me.” In an appearance on Joan Rivers’ daytime talk show in 1989 (just two years after Rivers’ own late night show was cancelled by Fox), Byrd remarked that her late night show was “adult entertainment” about “turning you on and tucking you in,” dramatically different words than Carson’s insistence for his show’s tameness because people fall asleep to his (oft-objectifying and insensitive) comedic bits on The Tonight Show. As a feminist, Byrd understood the political power of her platform and how it allowed her to speak to issues of deep concern for the sex workers and queer figures that frequently appeared on her show. Her identity and industrial positioning on a public access channel remain unique and worthy of deeper study.

Localizing late night also allows us to explore series such as The Mystery Hour, hosted by Jeff Houghton, to better understand regional specificity and the resilience of late night’s historical hegemony. The show is carried in seventeen different markets across the Midwest and South, including Arkansas, Mississippi, Kentucky, and even Oregon. Filmed in Springfield, Missouri in front of five hundred people, its Midwestern sensibility is undoubtedly influenced by Carson’s similar self-presentation, as that folksiness has long been considered quintessentially American for white Americans. The show, unsurprisingly, is overwhelmingly white and includes field segments at Ozark Technical Community College and jokes about Silver Dollar City, a local amusement park. This regional specificity alludes to how late night could be interrogated with more attention to local and regional production, even as the show’s nichification of whiteness and perpetuation of Midwestern (read: white) sensibilities as innately tied to late night programming only reinforce the systemic exclusion of marginalized individuals at every level of late night’s production.

Ultimately, the hope is that further research on local and regional late night production will discover and amplify those voices who have intentionally been dismissed or ignored throughout late night’s history (or perhaps, allow us to directly address the historical links between whiteness and de-politicizing late night’s material) . If systemic changes continue to slowly but gradually occur, like in the instance of Jimmy Kimmel’s leave of absence potentially allowing for black women and other women of color to have opportunities guest hosting, then we might slowly be able to push back on late night’s hegemony in order to re-calibrate how we interpret and address late night’s cultural function.

Image Credits:

- Stephen Colbert’s re-named A Late Show, filmed from the comfort of his home. (author’s screen grab)

- Lilly Singh, the first bisexual and first woman of color to host a broadcast late night series, on NBC at 1:35am. (author’s screen grab)

- A grainy still from The Robin Byrd Show, one of the longest running late night series in U.S. history. (author’s screen grab)

- Russell Peterson, Strange Bedfellows: How Late-Night Comedy Turns Democracy into a Joke (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008): 18. [↩]