OVER*FLOW: End Goal? The Promises of the US Women’s Soccer Team

Elizabeth Nathanson / Muhlenberg College

It is not a stretch to claim that representations of the US Women’s Soccer team are emblematic of many contemporary trends in the state of feminism and popular culture. Upon winning the FIFA World Cup in July, the team has inspired both support and criticism. This victorious team is regularly situated in relation to the lawsuit the players filed in March against US Soccer for gender discrimination for paying women team members far less than men. Widely reported upon, the stories surrounding the soccer players depict a range of postfeminist, neoliberal, consumerist discourses which celebrate individuality and the promise of youthfulness. Absent from many of these discourses, however, is how the team’s representation finds strength in embracing the past, celebrating not just future generations but also the history of soccer players and feminist activism. Doing so gestures to a feminist politics that does not exploit the promise of youth, but rather finds strength in the invisible, unrewarded labors of women who have come before.

For those celebrating the FIFA win, the women’s team is seen as representative of a kind of American patriotism that resists the explosions of misogyny, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia, and other expressions of hate bubbling over in America. Opinion pieces such as those by the Editorial Board of The New York Times celebrate the win as representative of how the team has “earned a payday at least equal to their male counterparts.” [1] Megan Rapinoe in particular is seen as emblematic of “progress,” standing as a highly visible gay athlete who is a distinctly powerful role model. [2] On the other hand, the National Review offers a tame example of the vitriol that is also being hurled at these players who are blamed for “politicizing” sports through language deemed “disgrace[ful].” [3] Here, and elsewhere, these women are criticized for being “killjoys,” [4] for stepping out of their lane by making the personal political. Mainstream editorials like these speak of the kind of “popular misogyny” that Sarah Banet-Weiser argues has risen in response to and alongside “popular feminisms.” [5] This tension between celebration and hatred is only further illustrated when one dips a toe in the comments posted on Rapinoe’s Instagram stream. Here, comments vacillate wildly between those applauding her status as a role model and those spewing homophobic and misogynist garbage.

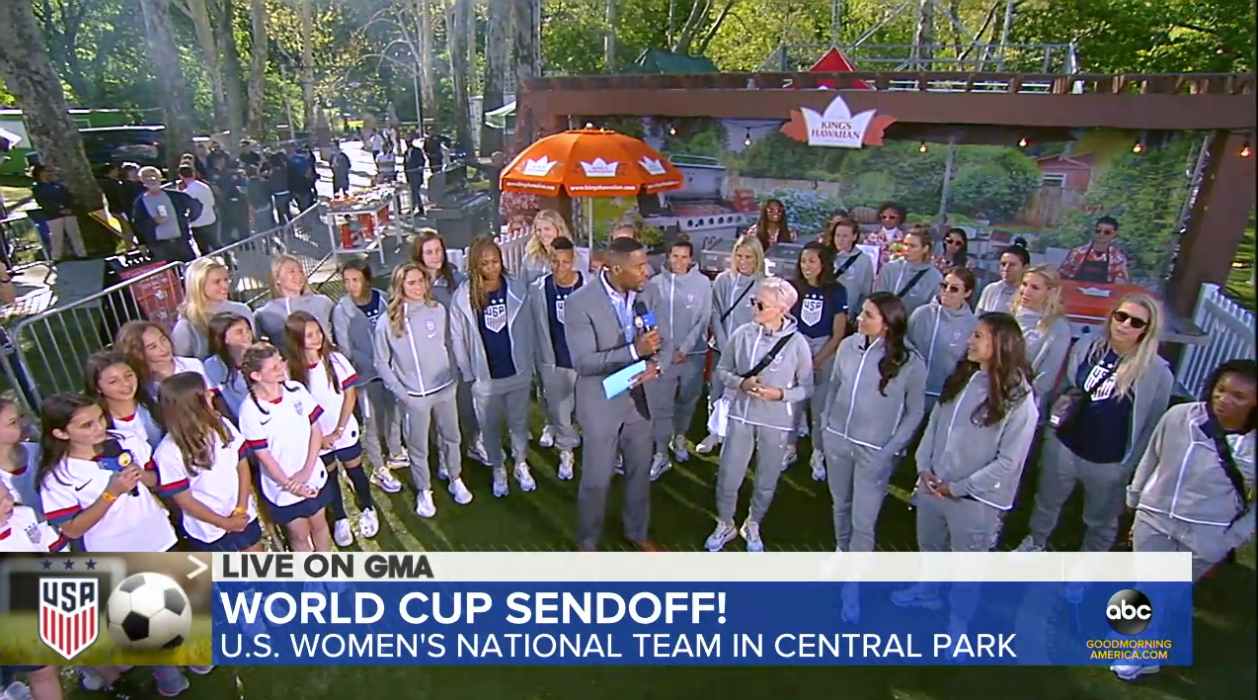

Given the way these athletes have ignited such furor, it is no surprise this team has been taken up by the media and by corporations seeking to profit from the popularity of these women, specifically through capitalizing on their youthful can-do spirit. [6] In May, before the World Cup, the team appeared on Good Morning America. Standing next to a group of young girls, players were asked about their status as role models. [7] Immediately following their World Cup win, Nike released a commercial titled “Never Stop Winning” featuring the players. Like the 2018 Nike advertisement titled “Dream Big” featuring such athletes as Colin Kapernick and Serena Williams, “Never Stop Winning” extols the virtues of individuals striving to achieve in the face of adversity, and the success promised by creative determination.

This Nike ad, like the GMA appearance, depicts the team as representative of future change that is gendered in nature. In black and white stills with voice over, the commercial uses a gritty authenticity to position these players as a righteous, virtuous group that can stand as trailblazing role models to who are moved to “believe.” This forward-looking celebration deploys the future tense in voice over as well as in visual images. The photographs of the current team along with the release of the video immediately following the World Cup win situate it very much in the “now,” and then bind it to the future image of youth, particularly young women.

With a few photos of the faces of earnest young girls interspersed with those of the well-known athletes, the sense of possibility is tied to these young bodies. This construction of the productive capacity of girls binds them to the Nike brand of politics in which power structures such as capitalism not only remain intact but profit off of these fantasies of innate feminine ability. While notably affecting, this form of corporate feminism risks functioning as a kind of “cruel optimism” in which “the scene of fantasy…enables you to expect that this time, nearness to this thing will help you or a world to become different in just the right way. But, again, optimism is cruel when the object/scene that ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain the expansive transformation for which a person or a people risks striving.” [8] In the Nike commercial, winning is associated with girls and the liberal feminist ideal of equal pay. When we are also facing attacks on reproductive rights, the lack of adequate caretaking workplace leave policies, an epidemic of sexual harassment and assault (just to name a few contemporary feminist concerns), equal pay cannot be the only, or more specifically, end goal for feminism. Furthermore, to place that goal on the promissory shoulders of this one team or individual girls to fix in the future rather than situate it in the complex system of economies and politics, strikes me, as the mother of a young daughter, as passing the buck.

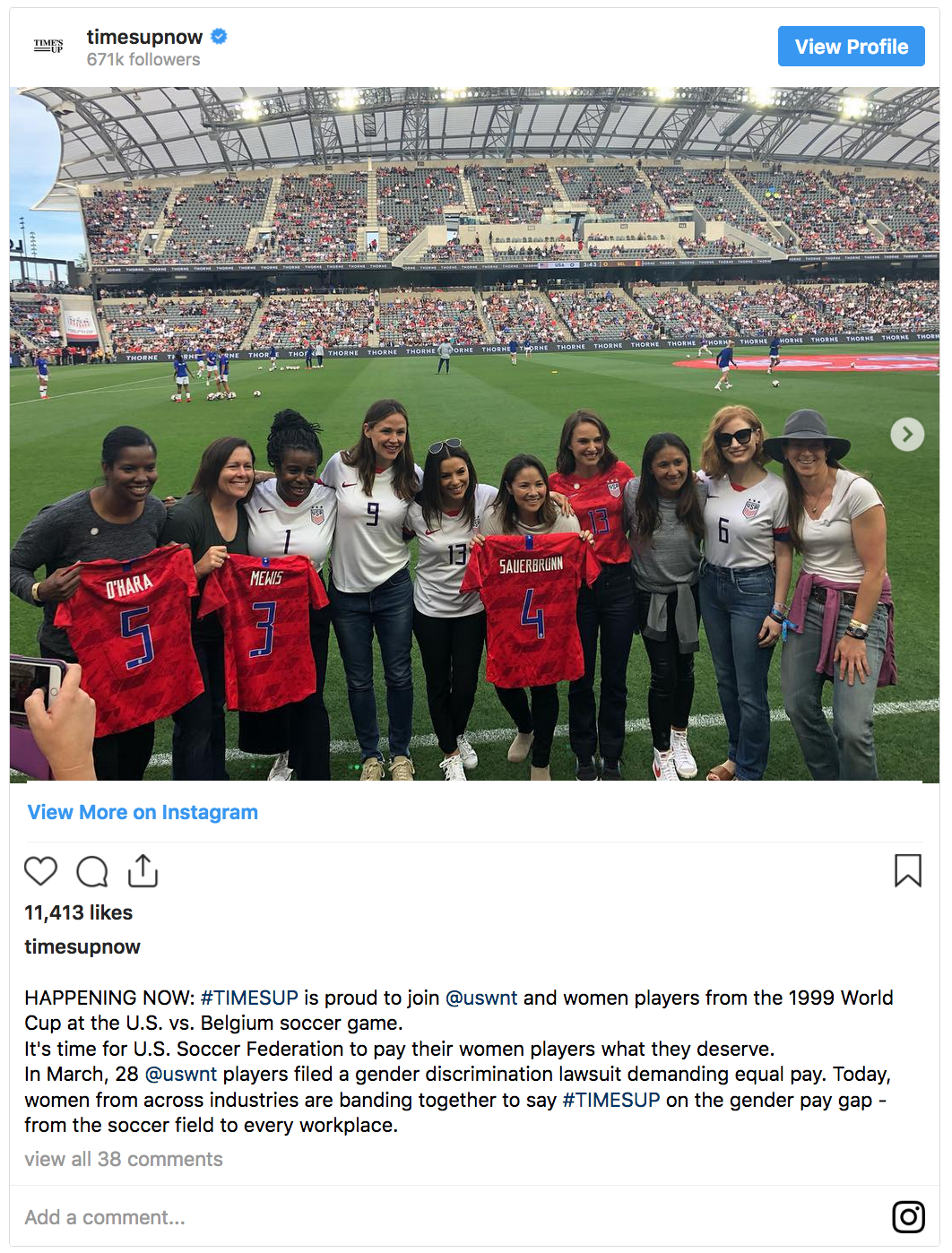

The most exciting depictions of the US Women’s Soccer team, however, are not those that depend upon a forward-looking sense of possibility bound to the bodies of girls, but the invocations of sisterhood among the athletes and the attention to the history of discrimination that creates alliances across generations of teams and players. The media landscape has been filled with images of the players celebrating goals and wins in raucous jubilant solidarity. In April, celebrities like Jennifer Garner and Uzo Aduba, supporters of Hollywood’s gender equity organization Time’s Up, “showed their support” by wearing jerseys of players from the 1999 team while watching the current American team play a match. [9]

Such display of bonds across generations of players renders visible the work of past women’s teams, underscoring how the 2019 team is not the only group of women deserving of reward for their labor.

Furthermore, on social media feeds, team members chant “four stars” in celebration of their win, in effect connecting their team to previous three teams who have won the World Cup.

By looking backwards these representations speak of a feminist politics that always stands in relation to historical context. Such inter-generational connections undermine arguments against systemic gender equality which might claim that this particular team is uniquely talented and therefore deserving of more money. Instead, when players are featured on the official team Twitter celebrating their contribution to the “four stars,” this collection of women is shown to be participating in a larger history of women athletes, all of whom are deserving of accolades, not merely those who are able to be dubbed the “best.” Rather than standing as static role models who endlessly pass the torch of feminist responsibility to younger generations, the “four stars” chant gives credit to the other teams, embedding feminist politics as never just about individuals or individual teams but always already rooted in history.

Image Credits:- The US Women’s Soccer Team on Good Morning America. (Author’s screenshot from Good Morning America video)

- Nike’s “Never Stop Winning” Ad. (Author’s screenshot from Nike video)

- Time’s Up Supporting the US Women’s Soccer Team.

- The Team Celebrating “Four Stars.” (Author’s screenshot from the USWNT Twitter post)

- The Editorial Board, “Show Them The Money,” The New York Times, July 8, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/08/opinion/world-cup-usa-pay.html?searchResultPosition=10. [↩]

- Christina Cauterucci, “Megan Rapinoe Is a New Kind of American Hero,” Slate, July 2, 2019, https://slate.com/culture/2019/07/megan-rapinoe-gay-icon-2019-world-cup.html. [↩]

- Dennis Prager, “We All Wanted to Love the Women’s Soccer Team,” National Review, July 16, 2019, https://www.nationalreview.com/2019/07/womens-soccer-team-megan-rapinoe-disgrace/. [↩]

- Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017). [↩]

- Sarah Banet-Weiser, Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018). [↩]

- Anita Harris, Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Routledge, 2004). [↩]

- Katie Kindelan, “US Women’s Soccer Stars Hope 2019 World Cup Inspires Girls to ‘Believe in Themselves’” May 24, 2019, https://www.goodmorningamerica.com/culture/story/us-womens-soccer-stars-hope-2019-world-cup-63250365. [↩]

- Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University PRess, 2011), 2. [↩]

- Jess Cohen “Jennifer Garner, Eva Longoria and More Form the Ultimate Squad at US Women’s Soccer Game.” E! Online, April 8, 2019, https://www.eonline.com/ap/news/1030676/jennifer-garner-eva-longoria-and-more-form-the-ultimate-squad-at-us-women-s-soccer-game. [↩]

you so much for this. I was into this issue and tired to tinker around to check if its possible but couldnt get it done. Now that i have seen the way you https://www.ucbrowser.vip/ did it, thanks guys

with

regards

us women soccer team is amazing