Complaint as Diversity Work in Sports Media

Courtney M. Cox / University of Southern California

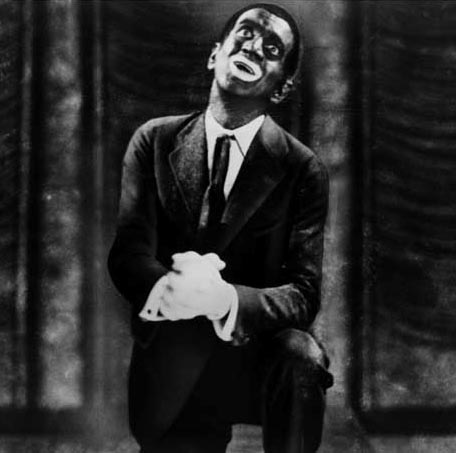

It started off like any other day at ESPN. I walked into work, set my bags down, and then I saw him, inside of a monitor in Studio F—DJ Steve Porter, in what appeared to be blackface. The award-winning DJ created pre-recorded monthly mashups which aired on SportsCenter, the network’s flagship program. This edition of Porter’s segment focused on now-retired NFL legend Randy Moss and his equally legendary press conferences. At the end of the video, Porter, who is white, is briefly shown behind his turntables wearing a Randy Moss mask and an afro wig.

The brevity of the shot, combined with the dark lighting of the set, gave me the minstrelsy vibes which first caused my concern. Aware of both the intention of the segment (to celebrate Moss’s career) as well as possible perception (the lighting seems to transform the mask into a paint-like look), I decided to ask a few of my fellow black co-workers if they had seen the piece. All of them had, and while some wanted to speak out, the precarity of their positions as either project-based (temporary) or entry-level prevented them from alerting their higher-ups. One friend told me, “You know how few of us there are in the control room and newsroom. If one black producer is on vacation, another is off work, and the third works the late shift, who’s there to call it out?” I thought about the fact there were less than five black producers or supervising producers at the so-called Worldwide Leader in Sports and considered my own helplessness and vulnerability as a black woman barely old enough to drink and considered entry-level myself within my department.

I watched another hour of SportsCenter, and another pitch-black Porter. I decided to email my former boss, an influential supervisor in my department. He agreed to meet with me on my lunch break. I entered his office and told him about the segment. Seeing my concern, he looked at me empathetically. “Court, I’m going to call the supervising producer in the control room right now and let them know, but first you have to tell me what blackface is.”

As I began to explain the term and its history to my former boss, a middle-aged white man from Massachusetts, I realized in such a vivid way why discussions surrounding difference or “diversity” in the newsroom matter. After calling the supervising producer, he alerted me to the fact that they had received viewer complaints about the segment and had made a decision not to run the Porter mashup in upcoming SportsCenter airings.

It was my first time voicing concern about anything at ESPN, but in hindsight, my five years as an employee left much to be desired across the multiple locations and departments which often fulfilled me professionally but constantly tried my spirit and sanity as I moved throughout a company marked twice by race and gender. On-air talent slid me their phone numbers on show rundowns (and demanded I call them) during commercial breaks, opportunities to travel were limited for me and fellow female employees to “protect” us from “what happens on the road,” and when a scandal erupted surrounding an affair between a female production assistant and an older, married male baseball analyst, many women voiced private concerns that “she might ruin things for all of us.” I remember feeling nervous about complaining, as though I would mark myself as ungrateful, or too sensitive.

Years later, in a different position now studying these issues in an academic capacity, I see how little has changed. The white, Western-centric, heteropatriarchal industry that is sports media continues to produce rosters which fail to represent many of the athletes and fans which comprise and consume its content on a daily basis. Take, for example, recent discourses (and discipline) surrounding Jemele Hill and her tweets, or the recent Fantasy Football auction held on the ESPN lawn (which resembled a shot-for-shot remake of Jordan Peele’s auction scene in his 2017 film Get Out) which received backlash from athletes and viewers alike given the segment’s slavery overtones. Whenever these media mishaps occur, the question seems to always surface—there wasn’t anyone in the room who thought this was a bad idea?

And far too often, there isn’t. In the most recent report conducted by Dr. Richard Lapchick’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES), the Associated Press racial and gender report card rated the lowest out of all the reports—racial hiring received a C+, while gender received its fourth consecutive F. While the report focuses on print and online sports media (as opposed to my previous career in sports broadcasting), it should be noted that if ESPN’s numbers were removed from the report, the numbers would become significantly less diverse. If one of the “leaders” in difference still fails to create an inclusive culture and content, how can we begin to conceptualize a sports media landscape which offers a richer, more diverse range of people, backgrounds, and beliefs? And how can online platforms serve as new possibilities to engage with difference when even one of the latest enterprises, The Athletic, urges us to “fall in love with the sports page again” even as former National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) president Gregory Lee Jr. reports its staff comprised of 87.3% white (with 75% of those white males) journalists?

On a podcast hosted by one of The Athletic‘s editors-in-chief, Tim Kawakami, he discusses the report of the company’s diversity woes with Marcus Thompson, a black columnist for the sports media website. Thompson says, “I’m the representative, I guess. They call us the four-percenters now because there’s only four percent black people…even how we got our jobs…there’s wasn’t an application.” While I appreciate their perspectives as two men of color addressing the lack of diversity within their ranks, the emotional exhaustion of representation is not lost on me. Thompson is hesitant to complain publicly about the lack of racial and gender diversity within his company, which he admits, reminding us of the potential cost of complaint for those seeking to stay employed.

Diversity work, according to Ahmed, is both the work we do to transform an institution and the work we do as those located outside of what is considered the norm. [2] The complaint emerges out of the challenging of these norms, whether explicitly, as I did in my boss’s office, or simply by how we appear in the space, disrupting the idea of who is allowed to be there. I am encouraged to forge new possibilities within literature related to identity and representation in sport and sports media while also understanding the weight complaints carry, as well as the risks involved. I believe improvements in the industry require a multi-pronged approach which 1) emphasizes the role of allies in these spaces to speak up, reducing the amount of emotional labor required of women and people of color, 2) employs more diverse voices and identities, expanding the breath of possibilities in content, and 3) reconsiders the complaint as a sharpening mechanism which allows for the potential transformation of industry culture. After all, “feminism,” as Ahmed writes, “is about giving a complaint somewhere to go.” [3]

Image Credits:

1. A still shot of DJ Steve Porter in his video remix “One Clap.” (author’s screen grab)

2. Al Jolson, the highest-paid and most famous entertainer of the 1920s, often performed in blackface.

3. The Athletic describes itself as “the new standard in sports journalism,” but has been criticized for lack of diversity within its ranks.

Please feel free to comment.

- Ahmed, Sara. “Complaint as Diversity Work,” feministkilljoys, November 10, 2017, https://feministkilljoys.com/2017/11/10/complaint-as-diversity-work/. [↩]

- Ahmed, Sara. “Diversity Work as Complaint,” feministkilljoys, December 19, 2017, https://feministkilljoys.com/2017/12/19/diversity-work-as-complaint/. [↩]

- Ahmed, Sara. “Complaint as Diversity Work.” [↩]