What Happens When Chinese and Western Podcasters Meet?

Siobhán McHugh /University of Wollongong

The success of podcasting, in the English-speaking world at least, is closely linked to its emphasis on the personal. Podcasts have hosts, not the more formal “presenters,” and these hosts, who often speak directly into our ears via our headphones, are like new friends. So how would podcasting work in a culture where “people’s sense of themselves as individuals atrophied…” That quote is from the Chinese satirical novelist, Yan Lianke, profiled recently in The New Yorker. [1] Lianke, mentioned as a potential Nobel Prize winner, attributes the “dark, fierce realism” of contemporary China to decades of living under a highly controlling Communist government.

With the post-Mao reforms of the last four decades and recent globalization and economic growth, many Chinese are reclaiming personal space, a development that Chinese media scholars Wanning Sun and Wei Lei call the “privatisation of the self.” Sun and Lei describe in fascinating detail how the market-driven transformation and social stratification of China have had a direct impact on perceptions of intimacy. [2]

In a society where the very notion of individualism was anathema for so long, how would the promise of digital intimacy, the implicit foundation of so much of our engagement with podcasts in the West, be received?

That’s the question I asked myself in October 2017 as I prepared to give a keynote on Tuning Into the Podcast Revolution, in Chengdu, China, at the General Assembly of the Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union (ABU), whose members broadcast to over half the world, some four billion people.

Would audio storytelling’s ability to build empathy and connection, prized by Western radio makers and podcasters over decades, resonate in a nation where, Lianke asserts, Communism had “made it impossible to express true feelings in conscious life…”

The short answer is yes, absolutely. The interest was palpable and I was subsequently invited by the ABU to run an intensive podcast training workshop for participants from China, Vietnam and Malaysia.

In the run up, I held a masterclass in Sydney for delegates from China Radio International (CRI), the English language arm of the state broadcaster. Many see CRI as part of a global Chinese push to conduct soft diplomacy. But the persuasive power of podcasting appears to have largely slipped under the radar. In the class, I hesitated before playing a clip from Serial Season One, thinking it might be too old hat—it had had c.300 million listeners by then and been the subject of countless articles. “What do you know about Serial?” I asked, before bringing up the slide. A broadcaster reflected. “It’s something you have for breakfast?” He was not making a joke. That’s when I realized what cultural difference truly means.

It’s not as if podcasting does not exist in China. Far from it, but it is different from Western storytelling and long-form conversation formats. China’s commercial podcast market is worth over 7 billion US dollars a year, based largely on subscribers who pay to access self-improvement and educational content, hoping to gain an edge in a highly competitive society. Lei has documented another popular set of audio products, distributed via listening apps and online platforms, which cater to two main streams: “knowledge products,” including audio books, poetry shows, business and finance; and “healing” content, which offer advice on personal and relationship issues, love and intimacy. Offerings tend to be short (under ten minutes) and simple: constructed of voice and music, without fancy production. [3] The numbers are staggering: Ximalaya FM, China’s biggest platform for shared audio content, reports 400 million downloads of its app. It has recently invested in an American podcasting distribution startup, Himalaya Media, which can monetize content by having listeners “tip” small amounts.

In my residential workshop, I wanted to see how participants responded to the Western podcast canon and how they might adapt it to cultural taste. Every morning I deconstructed the theory and practice of Anglophone podcasting, playing examples, analysing formats, structure and content, and expounding the grammar and logic of podcasting as a distinct media format, capable of producing “enhanced intimacy” compared to radio. All had brought, at my request, an interview in English on the theme of “absence.” Now we began to shape these into crafted stories, considering the choreography of sound, how layering and placement and even—especially—silence can alter impact and engagement.

The three Chinese participants from CRI had impeccable English, tertiary qualifications in arts, science and business, and over three decades’ experience between them as radio broadcasters. On Day One, I sent them out around the campus to gather sounds for a one-minute “audio postcard” from the university. The exercise showed how powerfully sound itself could evoke a place—they captured strange-sounding birds, the buzz of students in a café, the peace of a lake and its resident ducks. One, Zhi Ruo (not her real name, which she preferred not to use), scripted it as a moving note to her young daughter. The exercise convinced her, as she said later, that podcasting could function on a micro-level that allowed for content that radio could not:

Radio would not have the tolerance for you to do such family-bound things, you know, you’re pretending you’re speaking to just one person … your relative or your beloved one. So you’re taking advantage of a public platform to express your personal feeling. That is not okay … So, yeah, podcast, it gives me more “enhanced intimacy” to do that.

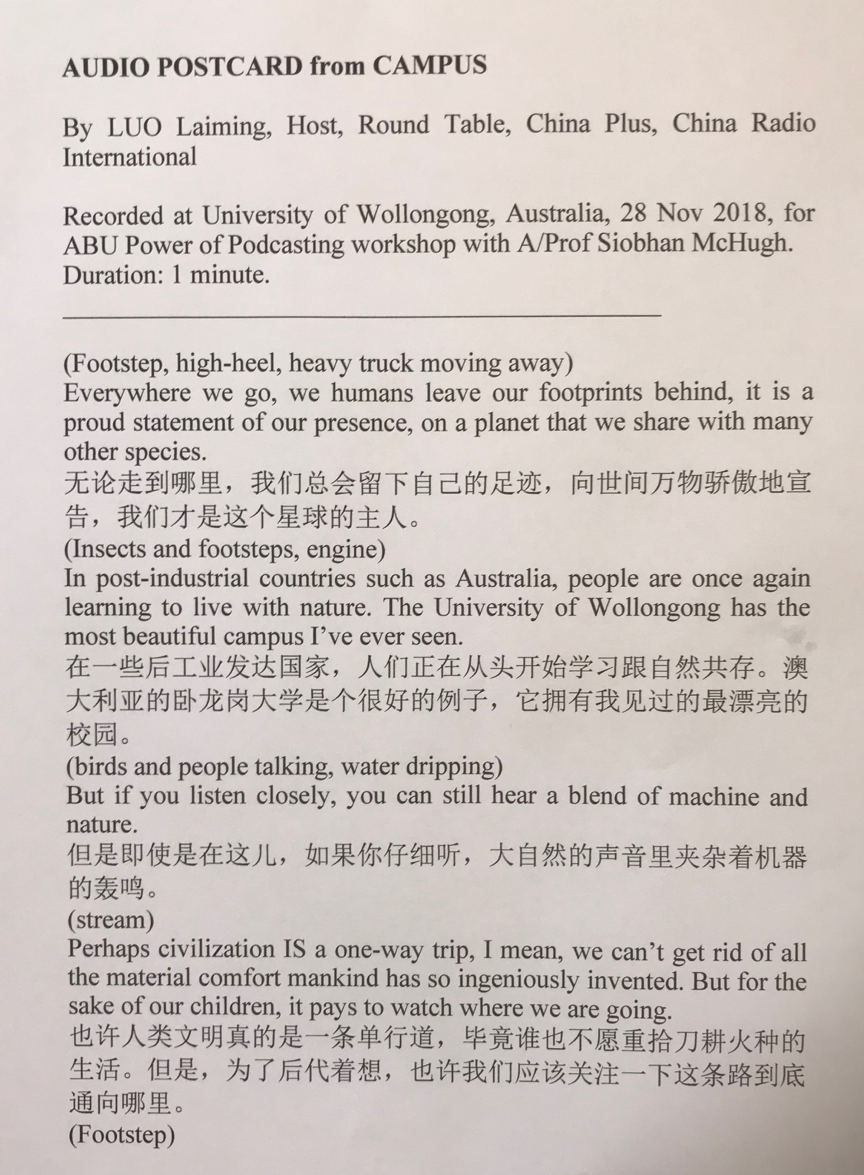

Luo Laiming, aged 32, who co-hosts a current affairs discussion program on CRI, also took to this style of audio crafting with alacrity. His sixty-second “postcard” (listen HERE) was a polished blend of philosophical reflection and personal commentary, including the line, “The University of Wollongong has the most beautiful campus I’ve ever seen.” This simple statement carried more meaning than we first realized, as Laiming explained:

This is the first time I tried in my writing to use “I” instead of “one could expect.” I said “I have seen.” It’s always been my style on the show, when I go live on a talk show or in the movie review, that I write to hide behind the narrative, behind the language.

Laiming was not convinced it was a purely cultural factor; he said he knew a lot of people in China who were “not afraid of showing their true colours,” but that he had been raised as an only child with a father who was not easy to communicate with and so, “I kind of shut myself down.” But his early years of editing other broadcasters had taught him that authenticity was crucial to make people stay listening. “You could tell whether the hosts were being spontaneous or not, if the emotions they’re expressing are authentic or not … you could tell from their voices.” The informality of podcasting was now giving him the chance to try out a subjective tone.

But when Laiming re-voiced the audio postcard in Chinese, he found it quite different (listen HERE). “I’ve always paid attention to rhythms in English—more than the words. I’ve found this hard to represent in the Chinese language. Second thing is some of the translation. E.g. ‘on the planet that we share with many other species’: the English sounds a little modest; in the Chinese language I said it as ‘we are the owners of this planet.’ And there’s another part where I had to say the opposite of what I said in English: ‘we can’t get rid of all the material comfort mankind has so ingeniously invented’ becomes ‘we can’t go back to the traditional slash and burn.'” If Laiming does get to make a new podcast, he’d like to make one about Chinese fantasy and mythology—a topic that would surely yield rich pickings.

The vivacious Niu Honglin, the third Chinese broadcaster, aged 29, already hosts two podcasts available on Western platforms: Takeaway Chinese teaches aspects of the Chinese language and Illuminating Chinese Classics looks at Chinese literature, going back centuries.

In early production sessions, Honglin tended to include everything she had—ambient sounds, voice, music—just because she had it. “Like you’re a six-year-old, you’ve got a collection and you need to show all of them to your parents!” The effect was overpowering, undermining her very strong raw interview, with a man describing coming out as gay to his family, whose reactions were not all accepting. I advocated narration that does not bludgeon the listener into thinking a certain way, but invites them to reflect. We cut an overly-explicatory sentence, an intervention she appreciated. “It’s really much better, it’s [left] with the music, with the feeling, you’re wondering what will happen next. It’s just revealing.”

We finished our showreel, an eight-minute trailer for the forthcoming ABU/UOW podcast series called Stories From the Heart (listen HERE), two minutes before our workshop ended at 5pm on the Friday—as professional broadcasters, all respected the tyranny of a deadline.

It was left to Zhi Ruo to sum up how podcasting might differ from radio after all.

Doing a podcast, it’s not like a task that you go live every day on radio. Okay, I have to work now. Ding, Ding, Ding. The time is here. But for podcasting, whenever you have great ideas, you pop up your eyes and have shiny eyes, great ideas. There’s a light bulb, lighting up on the top of your head so you feel the passion to tell the story and strengthen that bond and make listeners want to come back and find you.

Will podcasting become a tool of self-expression in China? Passion is one key factor and politics is another. Perhaps, as with so much else, the market will decide.

Image Credits:

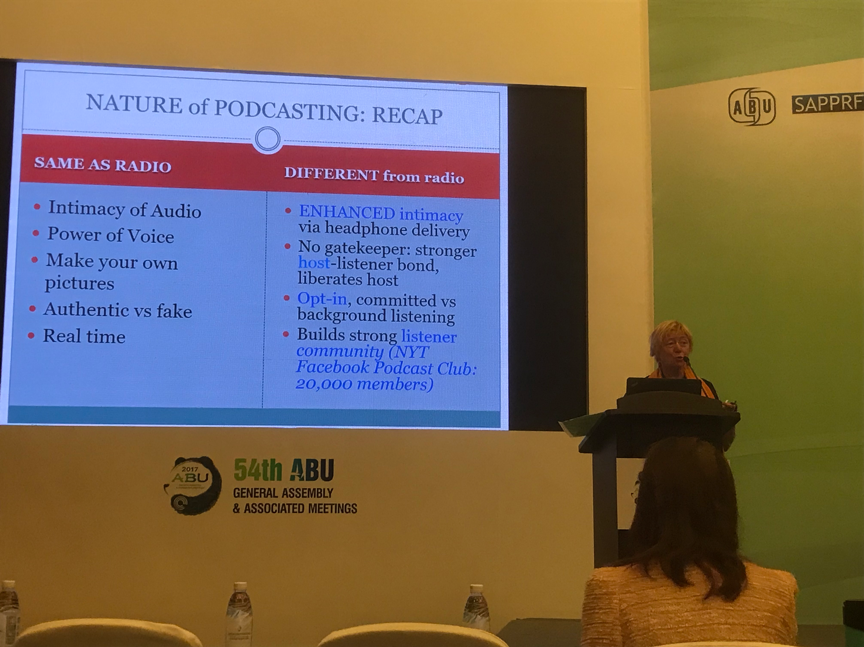

1. Siobhán McHugh delivers a keynote on podcasting to the Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union, Chengdu, China, October 2017 (author’s personal collection)

2. ABU/UOW Power of Podcasting workshop, Nov 2018. Participants point to their story on the theme of absence. Niu Honglin, third right, Luo Laiming on right, Siobhán McHugh, centre (author’s personal collection)

3. Laiming’s one-minute audio postcard script. (author’s personal collection)

4. Artwork for the podcast Illuminating Chinese Classics, from China Radio International (iTunes)

5. Workshop participants on the last day in studio. Niu Honglin second left, Luo Laiming in white shirt, Olya Booyar, Head of Radio, ABU, centre, beside Siobhán McHugh. Participants came from China Radio International, Voice of Vietnam, VTV, Vietnam and Institut Penyiaran dan Penerangan Tun Abdul Razak (IPPTAR), Malaysia. (author’s personal collection)

- Jiayang Fan, 2018. Yan Lianke’s Forbidden Satires of China. The New Yorker, 15 October 2018.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/15/yan-liankes-forbidden-satires-of-china

[↩] - Wanning Sun and Wei Lei. In Search of Intimacy in China: The Emergence of Advice Media for the Privatized Self, Communication, Culture and Critique, Volume 10, Issue 1, 1 March 2017, Pages 20–38, https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12150) [↩]

- Wei Lei. Radio and Social Transformation in China. Routledge, forthcoming. [↩]

The growing number of essay writing services is completely overwhelming. Sure enough, it’s hard to miss an essay writing service by the few steps you make. Every service is striving to be the best.