Cataloging Authorship:Mad Men at the Harry Ransom Center

Kate Cronin / UT Austin

In 2016, the Harry Ransom Center (HRC) acquired two high profile donations related to the critically acclaimed television series Mad Men: a donation of production materials, records, and correspondence from Matthew Weiner, the creator and head writer of the show, as well as a selection of props and costumes from Lionsgate Entertainment. Its provenance as the donation of highly regarded television writer-producer, Matthew Weiner, makes the Mad Men collection an incredibly rich starting place to consider contemporary television authorship. Somewhat less obviously, the donation of the Mad Men materials is also a unique opportunity to consider how institutionally specific archival best practices and individual intellectual labor within archives are informed by and contribute to popular, industrial, and academic constructions of televisual authorship.

The Harry Ransom Center is a unique institution. At once archive, library, museum, and exhibition center, the HRC strives to “provide unique insight into the creative process of writers and artists.” [1] The Center’s collections span photography, literature, film, and printmaking with a particular strength in the personal paper collections of prominent creative figures. When explicitly asked how he came to choose the Harry Ransom Center, Weiner explained:

I was at the Austin Film Festival and visited the Ransom Center and its extraordinary “Gone With The Wind” exhibit as a tourist. We were at dinner that night with screenwriting team Michael Weber and Scott Neustadter and found out that Michael had overseen the donation of Robert De Niro’s archives. He gave me [Ransom Center Curator of Film] Steve Wilson’s contact, we went to the museum again, I found out that Gabriel García Márquez, Norman Mailer and James Joyce had all been recently added, and from then on it was my hope to be part of such an amazing place. [2]

While Weiner has long referred to long-form, serialized television as art and rhetorically positioned himself as an artist, the donation of his personal papers to the HRC is a deliberate positioning of Mad Men and of Weiner himself within a fine arts context; a calculated investment in the long-term cultural capital that will be generated by situating his personal archive among long canonized figures of the art, photography, literature, and film worlds. [3]

The Mad Men collection arrived at the Harry Ransom Center as 150 banker boxes of correspondence, scripts, set plans, shooting schedules, call sheets, casting memos, outlines, notes, research binders, and press kits, as well as a selection of props and costumes. Cataloging these materials—the process of organizing and describing archival materials to most efficiently facilitate storage, access, and preservation—is an immensely time- and labor-intensive process. For this reason, it is common practice for most archival institutions to function with a significant processing backlog. However, the Weiner and Lionsgate donations of the Mad Men materials were made on the condition that the collections be processed right away and made available to the public for research as soon as possible. [4]

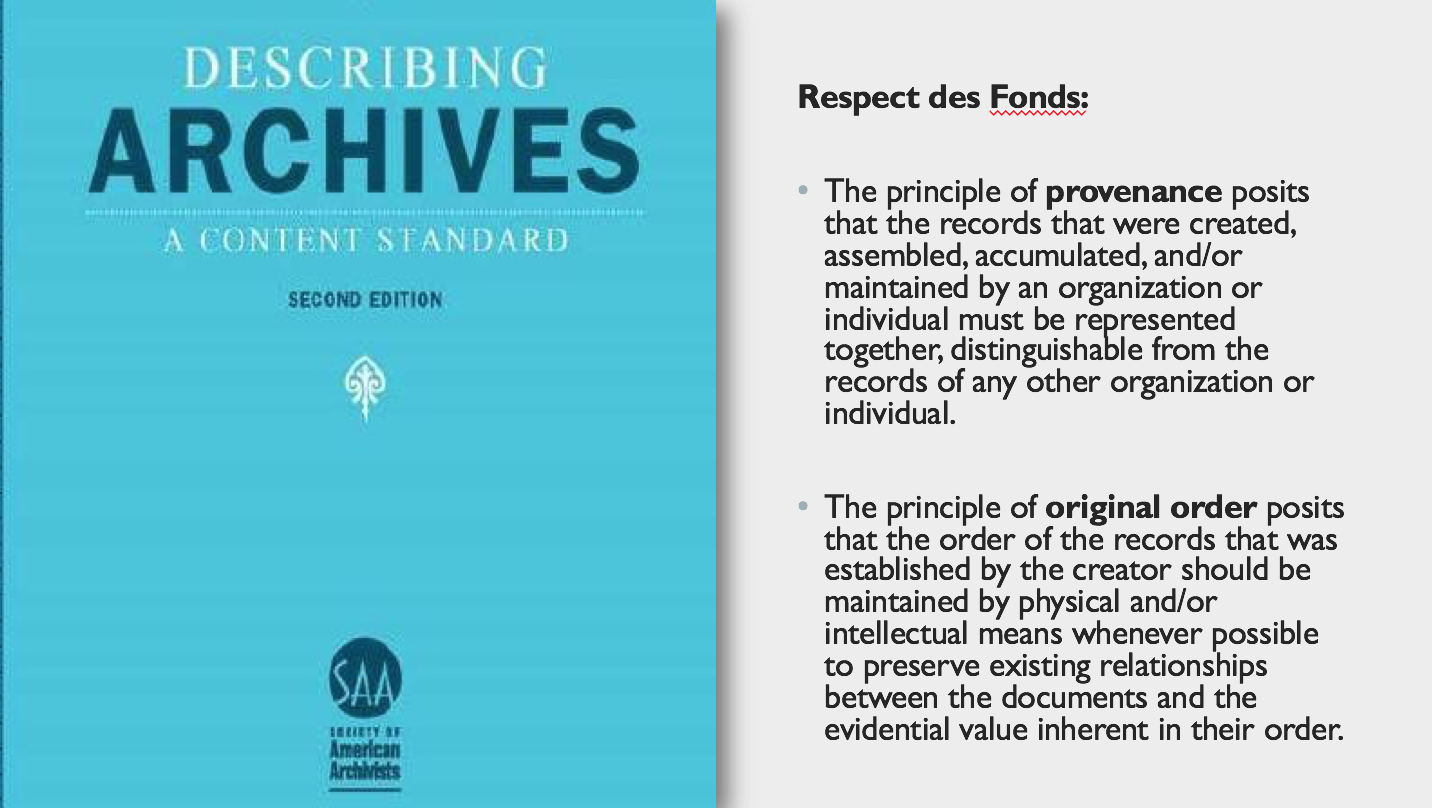

The collection, like the rest of the HRC collections, has been cataloged using a descriptive standard for archives, personal papers, and manuscript collections adopted by the Society for American Archivists: DACS (Describing Archives: A Content Standard). DACS facilitates the 19th and 20th century archival tenets of respect des fonds, encompassing the organizational principles of provenance and original order. Provenance dictates that archives be organized around a specific individual or organization designated as the “creator,” while original order dictates that archival storage and documentation reproduce the organizational logic of the individual or organization designated as the creator. For the Mad Men collection, this means that Matthew Weiner is designated as the creator of the collection, and the cataloging of the collection will document and reproduce his organization of the collection. This descriptive practice posits that the context provided by preserving Weiner’s organizational logics will provide additional insight into his creative process.

In my conversation with the HRC Mad Men cataloguer, Ancelyn Krivack, undoubtedly the person who will come to know the collection most intimately, Krivack noted that she has been most surprised by the extensive documentation of what a collaborative environment and multiplicity of creative visions it took to create Mad Men. Weiner himself has been very vocal about the team effort it took to plan, produce, and distribute Mad Men, from the show’s initial conception to its afterlife on various streaming platforms and now in collecting institutions. When asked what he hoped visitors to the collection might glean from the archives, Weiner responded: “I obviously hope that people who are creative can retrace our steps and see how we became interested in the parts of the story we were interested in, and that the creation of the characters and storylines in the show were the work of many people.” [5] This plurality of creative visions that Weiner enthusiastically affirms would seem to be in direct contrast to the resolutely positivist archival arrangement and description prescribed by DACS, which, in point of fact, was never intended to describe a creative process spanning numerous companies and creative individuals.

Terry Cook has theorized this disconnect between the positivist archival standards and practices formulated in 19th and early 20th centuries, and the postmodernist archival demands of the early 21st. For Cook, archives are not static, passive, neutral repositories that preserve objective documentation that can later be used to reproduce a unified and universally accepted narrative of the past. Rather, he argues, archives should document and describe process, as opposed to reifying conspicuous authorship under the guise of objective neutrality. Cook envisions an archival context that could describe a “dynamic multiple creatorship and multiple authorship focused around function and activity that more accurately captures the contextuality of records in the modern world.” [6] While this optimistic, postmodern archival schema sounds appropriate in theory, it obscures the financial, organizational, and legal challenges most archives contend with on a daily basis. Despite the scientific and systematic veneer of most archival schemas and descriptive standards, the messy reality of archival practice is a constant exercise in fitting square pegs into round holes. Moreover, postmodern archival theory significantly overstates the agency of archives and collecting institutions when it neglects to situate archives within a complex nexus of cultural, corporate, academic, and sometimes governmental interests and investments. For collecting institutions such as the Harry Ransom Center, everyday operations depend on relationships with individuals, such as Matthew Weiner, and organizations, such as Lionsgate Entertainmant, for donations, funding, support, and public relations purposes.

DACS will, however, provide Krivack with a few significant opportunities to point interested parties towards the more collaborative authorial process documented within the collection. Krivack has created a finding aid for the Mad Men collection, that is, a document that serves as a general guide to the materials within the collection. An essential part of any finding aid is the scope and content note which provides the archivist(s) with space to direct interested parties towards the highlights and limitations of a given collection.

If the Mad Men collection sets a precedent for the continued legitimation of television and television creators within a fine arts context, a more rigorous understanding of televisual authorship will require scholars, critics, and fans to cultivate a degree of archival literacy. A nuanced theorization of television authorship should not depend on the development of entirely new organizational schemas and controlled vocabularies within financially strapped public and private collecting institutions. Rather, television scholars have clear historiographical stakes in developing the industrial and archival literacies that facilitate a qualified understanding of how archives and archivists can at once mobilize the canonization of singular authorial voices while also (if, perhaps, somewhat more quietly) carefully documenting an inherently collaborative creative process.

Image Credits

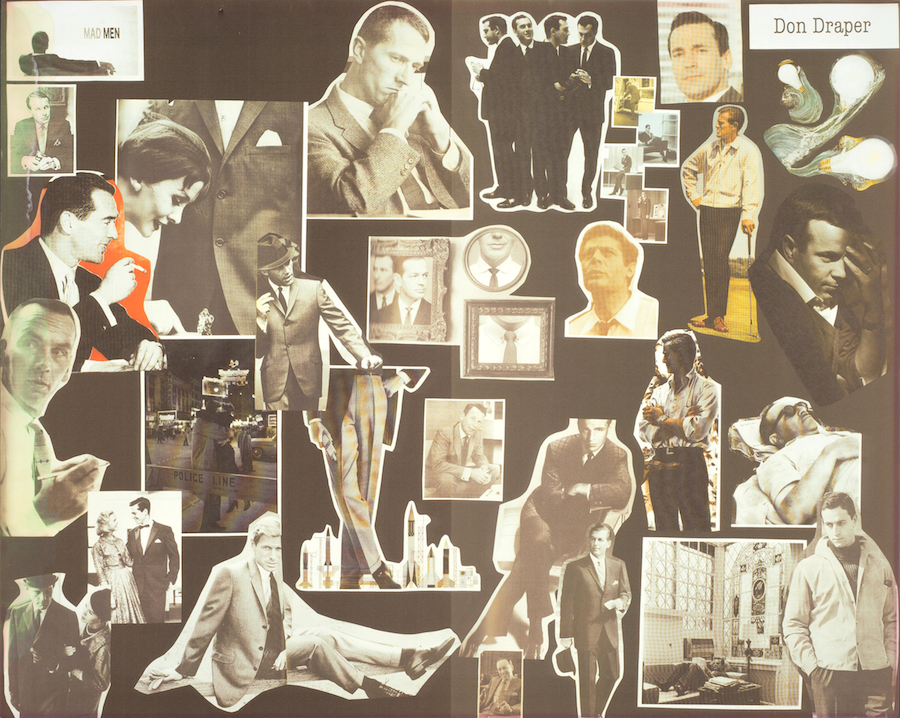

1. Don Draper inspiration board, part of the Mad Men collection at the Harry Ransom Center

2. The Harry Ransom Center

3. One of one-hundred-and-fifty bankers boxes of materials to be catalogued

4. Breaking down provenance and original order (author’s screen grab)

5. The Mad Men Writers’ room

- “About Us,” The Harry Ransom Center, 20 April 2017, http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/about/us/. [↩]

- Weiner, Matthew, Interview by Suzanne Krause, Harry Ransom Center Cultural Compass, 12 January 2017, https://blog.hrc.utexas.edu/2017/01/12/interview-with-matthew-weiner-creator-executive-producer-writer-and-director-of-the-series-mad-men/. [↩]

- It should be noted that Weiner did not receive a tax break for the donation of the Mad Men materials. [↩]

- Lionsgate Television, a co-producer of Mad Men, provided the funding for the processing and cataloging of the Mad Men materials [↩]

- Weiner, Matthew, Interview by Suzanne Krause, Harry Ransom Center Cultural Compass, 12 January 2017, https://blog.hrc.utexas.edu/2017/01/12/interview-with-matthew-weiner-creator-executive-producer-writer-and-director-of-the-series-mad-men/. [↩]

- Cook, Terry, “Archival Science and Postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts,” Archival Science 1, no.1, (2001): 22. [↩]

Despite the scientific and systematic veneer of most archival schemas and descriptive standards, the messy reality of archival practice is a constant exercise in fitting square pegs into round holes…

This is interesting. I liked your article. MAD MEN AT THE HARRY RANSOM CENTER

KATE CRONIN / UT AUSTIN is absolutely eye catching topic to pick. Great work done, mate.

I really impressed after reading this because of some quality work and informative thoughts. I just wanna say thanks for the writer and wish you all the best for coming!

Watching this and laughing like a klingon. yes I’m german.

we gonna tell you what you see…if you are horny..follow me…

follow me ..if you horny