Soundtrack Album Fandom and Unofficial Releases

Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University

I am a fan of soundtrack albums. I like score albums, compilation albums, and albums that feature both score and popular music. I own, and enjoy, the soundtrack album for (at least) one film I have never seen. Some of my earliest and most powerful music-related memories involve soundtrack albums. To my pre-teen brain, the backseat of a 1981 Honda Civic wagon, especially at night when the only light came from the dashboard, could be almost anything. For example, James Horner’s Star Trek II soundtrack album could make it feel like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise. That cassette (and others) eventually became a series of squeaks.

In my previous Flow columns, I have argued that soundtrack albums are worthy of more sustained attention. That analysis of soundtrack albums requires an address of their visual and textual information: covers, marketing materials, liner notes, and credits. [1] Having already claimed that soundtrack album audiences are not consumer dupes, I want to use this third column to consider unofficial soundtrack albums and fandom. To analyze soundtrack albums is to think about who makes them and the reasons for creation.

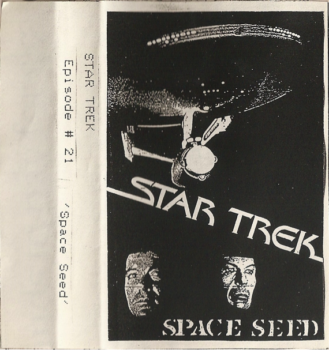

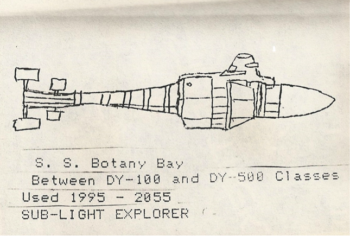

In my youth, I was also fortunate to witness the audio preservation of television. Much like those who created audio documents of Doctor Who episodes (whose work has now become the sonic spine for an animated episode), my brother Karl created his own version of Star Trek. My family did not own a VCR in the early 80s, and as children we did not have access to our own television, but we did have cassette players. Study of the TV schedule allowed decisions about which episodes to preserve. He placed a microphone in front of the TV speaker to transform (ephemeral) television into a (permanent) sonic Star Trek. Then he used a typewriter, a Xerox machine, a Star Trek: The Motion Picture poster, a library book and his terrific creativity to create artwork (above). This is a Star Trek he could control (and less scary than some official audio versions). This is a Star Trek that he co-authored. He did not do all this work for glory or profit. He did it all because he was a fan of Star Trek.

If we define a soundtrack album as one featuring at least 51% music [2] and with overtly signaled ties to another text (audio-visual or not), audio transfers of Star Trek and Doctor Who do not fit within these parameters. These recordings, like the programs they remediate, favor dialogue over music. They are transfers of a text’s complete audio contents. Importantly, they also follow an industrial practice, albeit a less common one, of releasing albums of the full sonic material from films, plays, and films based on plays. And here is the holy grail for some soundtrack fans: absolute sonic fidelity to the other “primary” text.

But even if we exclude my brother’s Star Trek from the category of soundtrack album, it does not mean it should be excluded from conversations about soundtrack albums. This text also highlights the fact that soundtrack albums remain under-examined in both fan studies and studies of audio piracy.

It seems reasonable to state that movie and TV fans buy soundtrack albums. I would also claim that many fans, when the market does not meet their needs, access bootleg soundtrack albums. Furthermore, some fans create soundtrack albums. By this I do not mean to suggest that fandom should ever be conflated with the illegal exchange of media. I do, however, want to argue that fandom drives the creation of soundtrack albums by corporations and individuals.

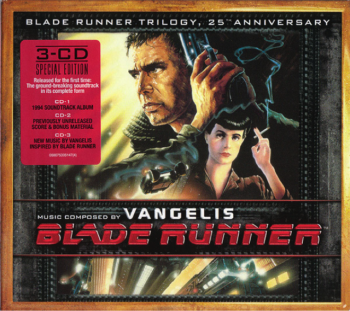

On the amateur side, soundtrack fandom pursues two frequently overlapping goals: 1) to create something that does not already exist, or 2) to “correct” the official release(s). The various albums associated with Blade Runner (1982) readily demonstrate both goals. Some facts: there are as many official soundtrack albums (three) as theatrically released versions of the film (three, not counting the “workprint”). But there are far more (official and unofficial) soundtrack albums than versions of this famously unstable text. Another installment of “spot the soundtrack (album)” on these albums could encompass far more than my allotted word count. But here is a greatly condensed account.

There have been Blade Runner soundtrack albums circulating since 1982. Though the film’s end credits promise a Polydor soundtrack album of Vangelis’s music, that album did not, and has never, appeared for reasons that remain murky. That year did include the first soundtrack bootleg (on cassette), and an official album of others playing the film’s music. The latter release, and the inclusion of some of the film’s music on a Vangelis compilation a few years later, did not nothing to stem the rapidly rising tide of unofficial releases. An official album of Vangelis’s film music belatedly arrived in 1994, featuring dialogue, sound effects and new music. It concludes with “Tears in Rain” rather than “End Titles.” This too, did not meet the needs of fans, who continued creating music-only albums like the one pictured above. [3]

The most famous, and best-loved, release is the two-disc “Esper Edition.” (it even has a “follow-up” release). More than one webpage features comments that purport to be from “(THE REAL) ESPER PRODUCTIONS.” The authors object to how the term has been used by others for profit, and emphatically state: “let us stress that our intention was always to make this a project by fans for fans. It was created out of love for Vangelis’ music‚ not money.” [4] The 2007 Blade Runner Trilogy is the most recent official release (other than subsequent re-issues). It includes the 1994 soundtrack album, another disc of music from the film, and a third disc of new music with vocal work from Edward James Olmos and Roman Polanski. On the second disc of “previously unreleased” material, Vangelis names a cue “Dr. Tyrell’s Death” that since 1982 fans have called “The Prodigal Son Brings Death.” The “official” name is unlikely to catch on. More importantly, despite the promise of “The ground-breaking soundtrack in its complete form” (see the sticker below), this release is not a complete offering of the music from (any version of) the film. [5]

Blade Runner invites, and receives, devotion. Yet why does the scholarly literature on the film’s fandom have so little to say about the albums? [6] More generally, why do fan studies scholars—who surely access legal and illegal soundtrack albums—overlook them? Is the labor of creating Blade Runner bootlegs categorically different from the labor of fans in creating filk songs, vidding, or composing fiction? The “Esper” curators, and others, create (fake) record label names, song titles, album art, and choose not only what sonic and visual material to include but how to arrange that material. All of these decisions create meaning.

Soundtrack album creators often profess, and fans request, fidelity to the film or TV program. Clinton Heylin, in his history of bootleg recordings, argues that fans wanted “original film soundtracks on record,” rather than re-recordings of the music. [7] Providing the exact audio material from a film may not appear to offer a “creative transformation” in the same way as other forms of fan labor. And their work is often associated with a vacuum in the market. But note that bootleg soundtracks have circulated through the same channels as other fan productions: conventions, tape trading and file sharing systems. Fans have created pirate recordings for themselves and other fans.

Expanding our sense of film music, fans can also impact our sense of their labor. As Nancy Baym recently noted: “Nearly, if not all, musicians are fans. Many fans make music.” [8] To this I would add that composers are also fans. Elmer Bernstein is responsible for the first album of Bernard Herrmann’s rejected score for Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966). Bernstein was a fan of his peer, and his Film Music Collection series (1974-79) created recordings of music he admired but was not readily (or legally) available. [9] In the following years, labels such as Varèse Sarabande and Intrada appeared in the U.S. market to help officially meet the desires of film music fans. These are small entities catering to a niche market, and take on the production risks that major media corporations deem unworthy of their time.

John Hughes once asked a silly question: “[W]ould kids want ‘Dankeschöen’ and ‘Oh Yeah’ on the same record?”

The Blade Runner releases are typically described as “score” albums, though nearly all include the 1930s pastiche “One More Kiss, Dear” (or the Ink Spots’ “If I Didn’t Care”). And while the soundtrack market favors score albums like those created by Bernstein, compilation albums are a staple of amateur production. Some, like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, eventually become official releases. The La-La Land Records’ album pictured above was released in 2016, “following 30 years of cobbled-together mix-tapes, YouTube playlists, Japanese bootlegs, and awkward negotiations with Swiss synthpop musicians.” [10] Unlike most other John Hughes productions, the film never had an official soundtrack release, in part because the writer-director explained: “I just didn’t think anybody would like it.” [11] Hughes was wrong, as the numerous (never only Japanese) bootlegs demonstrated over the years (though these releases seldom include Newborn’s music). The film’s use of particular mixes of (somewhat) obscure songs created a welcome challenge for fans to create their own albums. The belated official release is, unsurprisingly, incomplete [12] and so keeps alive the conversation between industrial and amateur production.

As long as films have featured music, audiences have enjoyed experiencing that music outside movie theatres. One music critic in 1986 wrote of soundtrack albums: “the record summons up once again the memorable scenes from the movie and sometimes even stirs the same emotions you felt in the theater.” [13] This remark opens a review of The Golden Turkey Album: The Best Songs from the Worst Movies, which, he argues, caters to the “bad-movie brigade,” an audience heretofore neglected by soundtrack releases. This same audience is one that scholars such as J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum in Midnight Movies (1983) were already lauding for their active responses to films.

This “brigade” is a creative, and active, audience: individual fans and clusters of fans who talk about and sing along with films. A group including audience members, artists, musicians and composers. Fans who record television, create art, crate-dig (literally or virtually) for specific versions of songs, and curate albums. There is more to be understood about the intersections of fandom and soundtrack albums, whether operating legally or illegally, whether creating or sharing, whether copying or buying.

Image credits:

1. Cover art and scan of art provided by Karl W. Reinsch. Included here with the artist’s permission. Permission to repost not granted.

2. Cover art and scan of art provided by Karl W. Reinsch. Included here with the artist’s permission. Permission to repost not granted.

3. Author’s scan of CD booklet.

4. Blade Runner Trilogy

5. Official release of the Ferris Bueller’s Day Off soundtrack album

6. The Golden Turkey Album: The Best Songs from the Worst Movies

Please feel free to comment.

- And this area is as complex as anything having to do with soundtrack albums. For example: The packaging for Nero’s Welcome Reality gives every indication that the work is tied to a film. But there is no film. The packaging misleads at least some folks. The album was in the “soundtracks” section of Ralph’s Records in Lubbock, Texas in late 2017 until I bought it (having enjoyed the use of “Doomsday” to promote Borderlands 2). [↩]

- This distinguishes the soundtrack album from radio dramas, audiobooks, and sound effects collections. [↩]

- The inside cover of the CD booklet features an image of Deckard visiting Holden in the hospital, though the image is not labeled. The image is enticing. It reminded me of the bottom of my Star Wars lunch box (red handle version) which showed a Stormtrooper on a big lizard. I could not remember seeing such a creature in a film that I thought I knew very well. The bottom of my lunchbox promised a larger and deeper world. But while this was an official promise, the images on my Blade Runner album were unofficial, illicit, and apparently illegal. [↩]

- https://www.discogs.com/Vangelis-Blade-Runner/release/3708848 and http://www.vangelis-rarities.com/index.php?methode=methode1&id=25 See YouTube for the proliferation of “Esper” versions that, at least there, are not for sale. [↩]

- News of Jóhann Jóhannsson’s rejected score for Blade Runner 2049 made me immediately wonder when (not if) I can hear that music. And another composer’s unused work for that film is already being put to use. [↩]

- Insightful volumes such as Will Brooker’s edited collection The Blade Runner Experience: The Legacy of a Science Fiction Classic (2005) and Matt Hills’s monograph (2012) for the “Cultographies” series neglect the albums (and say little about the film’s score). Media analysis, in large part, favors the image track over the soundtrack. But studies of media fandom do not have to follow this same path. [↩]

- Clinton Heylin, Bootleg: The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1994), 37. [↩]

- Nancy Baym, Daniel Cavicchi, and Norma Coates, “Music Fandom in the Digital Age: A Conversation,” in The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, Eds. Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (New York: Routledge, 2018), 151. [↩]

- See Gergely Hubai, “Mending the Torn Curtain: A Rejected Score’s Place in a Discography” in Partners in Suspense: Critical Essays on Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock, Eds. Steven Rawle and K. J. Donnelly (Manchester: Manchester UP, 2017): 165-173. [↩]

- Sean O’Neal, “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off soundtrack arrives after skipping the past 30 years,” The A.V. Club, https://news.avclub.com/ferris-bueller-s-day-off-soundtrack-arrives-after-skipp-1798251533. [↩]

- William Ham, “John Hughes: Straight Outta Sherman,” Lollipop, http://www.lollipop.com/issue47/47-02-03.html. [↩]

- The official description includes this disclaimer: “Due to licensing restrictions, a few of the film’s songs could not be included on this CD, but they are available elsewhere.” Of course, the “elsewhere” includes unofficial releases of the album. http://lalalandrecords.com/Site/Ferris.html [↩]

- Tom Popson, “At Last, A Soundtrack Album for People Who Enjoy Bad Movies,” Chicago Tribune, January 10, 1986: np. [↩]

This space might be used to discuss personal experiences in soundtrack album fandom. I have already done that above, but I can say more.

For example: the first (and only) time I attended a STAR TREK con I did not come away with any soundtrack albums. But I did go home with VHS bootlegs of V: THE FINAL BATTLE (1984) and Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE (1979), the latter of which came with free burned-in Japanese subtitles (betraying its status as a copy of the Japanese LaserDisc).

More importantly, I clearly recall the first time I had to do a little work to acquire a soundtrack album. After perusing the “soundtrack” section in the Hasting’s store in the town mall, I approached the gentlemen at the counter and expressed my desire to order the soundtrack for TERMINATOR 2 (1991). Perhaps because of my trepidation, or the fact that he could smell my teenage angst, the employee sternly informed me that the album did not “have the Guns ‘N’ Roses song.” I was, admittedly, a fan of the band’s earlier work, but I wanted the Brad Fiedel score (I was quite taken with the film’s theme and did not yet prefer the original film’s 13/16 time signature). Mercifully, but a bit grudgingly, he took my order. A few weeks later I had the CD, and still do. The packaging is pretty boring, but I was ecstatic that I had the right music to play while watching for mushroom clouds.