3 Ways that BTS and its Fans are Redefining Liveness

Michelle Cho / McGill University

Despite TV’s migration onto the web, live broadcasts of televisual events (sports, award show performances) still seem to confirm liveness as the essence of the medium. However, as many have observed, liveness and sharedness are also fundamental features of social media and internet use. [1] Accompanying the new norm of consuming television online, simultaneous engagement on social media about what one is watching and how one feels about it is a crucial dimension of a televisual event. Hence, liveness extends beyond instantaneous transmission and reception to the currency of sharing viewer experiences across platforms, apps, and networks. Fans’ efforts to multiply and expand forms of mediated liveness are already challenging national and medium-specific frameworks of popularity and publicity. To elaborate, I present the case of South Korean boy-band BTS, and the part played by their viral appearances on American music awards show broadcasts in developing their diverse, international fandom.

If you use Twitter, YouTube, or Spotify with any regularity you will probably have heard of BTS, since media coverage and social media mentions of the group have surged over the last year, after they won the 2017 Billboard Music Award (BBMA) for Best Social Artist—an award category decided by a combined tally of fan votes and overall social media engagement numbers. BTS just won the award for the second time, and are topping both North American and South Korean pop charts with their new album, released on May 18th. The music video for their latest single was streamed 41 million times on YouTube within the first 24 hours of its release, and BTS debuted its official “comeback” on a live broadcast of the 2018 BBMAs on May 20th. [2] As fitting the winners of a social media influence award, their performance was a viral event, with TV and the web co-creating an extensive field of social interactions. Fans mediated the broadcast’s liveness through tweets and posts, in the process remediating liveness by amplifying their experiences through this meta-discourse.

Here are three ways that BTS and their fans are expanding and redefining liveness across the thresholds of TV and social media:

1. Producing Real-Life Contents: Since their debut in 2013, BTS has produced and distributed behind-the-scenes video footage in short clips of backstage antics, dance practice videos, member vlogs, and gif-length video selfies via their group Twitter account and their BangtanTV YouTube channel. Some of the content has also taken the form of reality web-series, most recently Burn the Stage, distributed by YouTube Red. Other shows include Bon Voyage I and II, serialized travelogues featuring the band vacationing between tour stops, and Run BTS!, an ongoing series modeled on Korean variety show formats. [3] The latter are both produced and distributed by the Korean media company Naver through their VLive streaming app. VLive is specifically designed for celebrities (mostly pop idols, but including some indie and rap musicians, actors, and comedians), to directly address their fan-followers. The large, conglomerate-owned Korean cable music network Mnet also distributed two of the group’s series: Rookie King (2013) and American Hustle Life (2014). [4] Across these varied platforms (Twitter, YouTube, VLive, cable, and network television), BTS has delivered a steady stream of “real-life contents” (in the words of the group’s leader), inviting fans to engage on an intimate, quotidian basis, and granting a sense of having witnessed the band’s personal and professional growth over time. Many fans attribute their intense attachment to BTS to the regularity, frequency, and candor of the group’s transmedia contents.

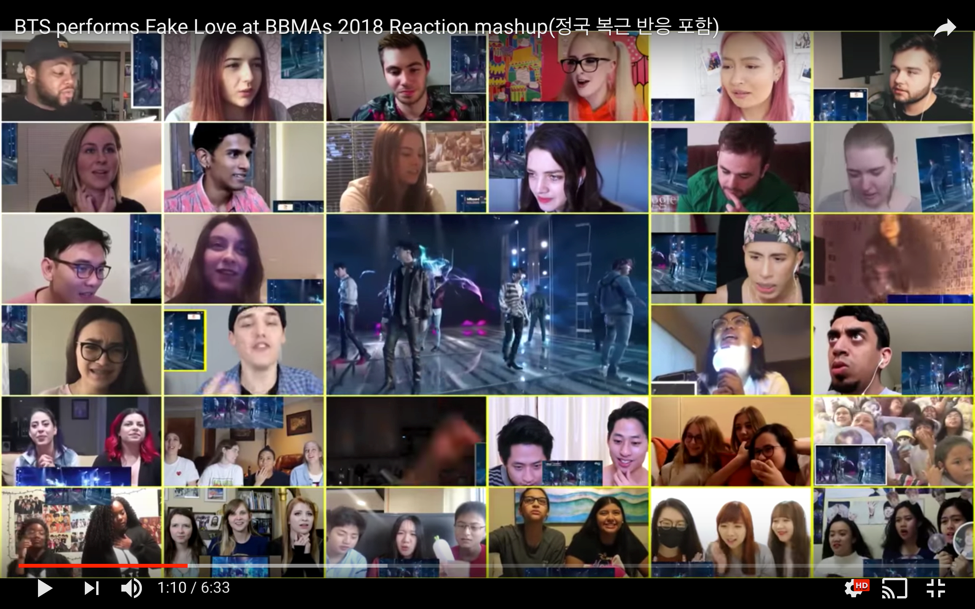

2. Archiving Liveness in Reaction Videos: Fans of BTS (and other K-pop artists) are also prolific video content producers, with a particular penchant for reaction videos. The genre of the reaction video, which is native to YouTube, emerged as a means of capturing shock, often in response to a horrifying or repulsive display. However, a growing proportion of reaction videos are focused on excessive delight, a structure of feeling that might characterize fandom. [5] Reaction videos capture liveness as both the claim to the “first time” watching, and as a spectacle of spontaneous affective experience. Fan reaction videos recast media consumption itself as transformative participation—fans are often primed to like the things they are reacting to, and their fan interventions are performances of identity that, in turn, help constitute the object of devotion. [6] Reaction videos create an archive of “first times” that new fans can binge, to create a compressed time sense that affords viewers fan nostalgia by proxy, the vicarious experience of history with the fan object through shared fan highs. [7]

The other important impetus for Kpop reaction videos is the centrality of dance to the K-pop genre. BTS is one of the most accomplished dance performance groups in the industry, in addition to being recording artists, and their choreography often draws gasps of awe from fans in their filmed reactions. Dance is said to create a sense of shared bodily experience. Artists can exploit the affective power of dance, as a powerful embodied mnemonic or to implicate the spectator in unsettling ways, particularly when it comes to the semiotics of race, gender, and sexuality in popular media. [8] While some critics complain that Kpop’s emphasis on visual spectacle is a tactic for attracting audiences through superficiality, dance also impels a corporeal, participatory culture. We see this in dance cover videos that are common to K-pop fandoms.

3. Multiplying Liveness through Screen-sharing and Fancams: BTS’s appearance on the BBMA’s led Mnet to license the content to make it available to Korean audiences, as it was otherwise exclusive to NBC/NBC.com and geo-blocked outside the US. The stream was also broadcast on TNT Latin America, with network commentators providing Spanish translation. Since I was trying to watch the show from Montreal sans cable subscription, I accessed the show through fan-posted streaming links on Twitter and Facebook. Fans used the Facebook Live feature to share their screens in relay, as streams would time out or get taken down for copyright violation after, at most, 10-12 minutes. I finally found two relatively stable streaming links where I could view both the Mnet and the TNT Latin America broadcasts. The contrast between the three feeds—Mnet, TNTLA, and NBC—highlighted the audience’s multi-sitedness; the pacing and commentary showed that BTS’s comeback performance was the primary draw for Mnet, a prominently advertised bonus on TNTLA alongside the “Latin” music artists (Luis Fonsi, Camila Cabello, Jennifer Lopez) who were the main attraction, and a curiosity for the NBC broadcast, the bulk of whose viewers might not be familiar with BTS or K-pop. The constant switching between streams affirmed the many fans, united in common cause, who were actively trying to facilitate access for other fans. Immediately after the broadcast ended, fans began posting their filmed reactions to BTS’s performance on YouTube, most using the Mnet broadcast clip (using NBC footage would result in a strike against the poster’s channel). These videos serve a nostalgic purpose, allowing viewers to revisit the moment of BTS’s unveiling on the show, whether they also watched the performance live, or are catching up after the fact.

A recurring complaint in these videos is the frequency and duration of crowd reaction shots, which interrupt the display of BTS’s intricate choreography. Fans who attended the live show quickly posted their own fancam footage, and shortly thereafter fans uploaded “fixed” versions—combined edits of the broadcast footage with fancam footage inserted in place of the offending crowd shots—to retain the broadcast clip’s superior sound quality and mobile camerawork. This suggests that fans enjoy spectacles of reaction when they’re fan-produced and they supplement rather than replace performance footage, and that a fabricated, optimized version of the performance boosts liveness by gratifying fan desires.

BTS have thrived as “global artists” by cultivating a data-savvy, affectively bonded participatory fandom that is driven to translate a sense of being-in-common across transnational, transmedia “zones of consumption.” [9] Despite cultural, linguistic, racial, and geopolitical differences, the group and its fans converge on multiple platforms, urging us to consider how liveness connotes a desire for collectivity that nonetheless registers the pluralism of our present, mediated life-worlds.

Image Credits:

All images in column are author’s screengrabs.

Please feel free to comment.

- e.g., Tara McPherson’s “Reload: Liveness, Mobility, and the Web,” in New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, eds. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Thomas Keenan (New York: Routledge, 2006), 199-209. [↩]

- A “comeback” refers to the live-broadcast, choreographed stage performance of the lead track of a new album that is a staple of the Korean music industry. Televised performance is key to pop music distribution and consumption in South Korea, with no less than six live performance shows produced per week, one on each major broadcast network and three on cable networks. [↩]

- Run BTS! cites the long-running SBS variety show Running Man. [↩]

- American Hustle Life focuses on the group’s introduction to the history and politics of hip-hop. Members meet and are mentored by figures like Warren G, Coolio, and LA-based hip-hop choreographers. The show has been criticized as appropriative, and the donning of hip-hop culture as mere commercial style is unfortunately a common offense in hip-hop inflected K-pop. This topic merits further consideration, but without space to do so here, I want to point out that some of the best discussions of racism and exploitation in K-pop take place among fans, many of whom are members of racialized minorities, as clearly demonstrated by the audience at the BBMAs. See, for example, The Jess Lyfe’s Vlog, “It’s Hard Being A Black Kpop Fan”; or Heidi Samuelson, “The Philosophy of BTS: K-pop, Pop Art, and the Art of Capitalism.” [↩]

- In “What’s Behind our Obsession with Game of Thrones Reaction Videos,” Laura Hudson pinpoints shared fan affect as the crux of what’s pleasurable about watching and re-watching reactions to even hyper-violent spectacle. [↩]

- Abigail De Kosnik, “What is global theater? or, What does new media studies have to do with performance studies?” In “Performance and Performativity in Fandom,” eds. Lucy Bennett and Paul J. Booth, Transformative Works and Cultures, Vol 18 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2015.0644 [↩]

- Paul Booth defines fandom as nostalgia driven in Playing Fans: Negotiating Fandom and Media in the Digital Age (Iowa City: The University of Iowa Press, 2015), 19, and Mark Duffett discusses the notion of “imagined memory” common to fans, as a means of accessing the past of their fan object, here and in Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 229-230. [↩]

- Lisa Nakamura, Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). [↩]

- Anna Cristina Pertierra and Graeme Turner, Locating Television: Zones of Consumption (NY: Routledge, 2013). [↩]

Hi. There is an issue for everybody who look for high quality articles. Will you seek different website? If you inquire me I will state absolutely no. This site is ideal for me!

Hi writer! Thank you for becoming here and publishing so well content. Here is a person who enjoy it and declare thank you so much!

In my opinion, not many bloggers own so countless tips to make unique, intriguing content. I appreciate doing it and I wish you didn’t lose the inspiration to write the unique ones!

I completely agree with the earlier audience. I presume the ideal determination and excellent views are wonderful basis to establish high quality material.

a true extension of their normal lifestyle and are comfortable chatting.

Pingback: #LightItUpBTS : Réflexions sur les conditions de réception de la soirée des Grammys Award par les fans de BTS, les ARMY. – AcaMania

The positivity and optimism conveyed in this blog never fails to uplift my spirits Thank you for spreading joy and positivity in the world