What is a Soundtrack Album? Or, Spot the Soundtrack Album

Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University

Soundtrack albums are having a moment. A member of indie rock royalty has admitted to being a soundtrack album devotee. An article analyzed a 2002 iPod as a time capsule featuring the era’s soundtrack albums. 2017 saw soundtrack albums drive vinyl and cassette sales. The Black Panther soundtrack albums are receiving extensive praise (and some of this mentions Prince’s earlier interventions). Moulin Rouge! (2001) was the sound(track) of Olympic figure skating. Variety has declared a “soundtrack renaissance.” And a media analyst, while noting the robust sales of soundtrack albums, wrote: “Video kills radio stars, but it may well be the film industry that leads the way in preserving the album as an artistic medium.” [1]

If the soundtrack album can preserve anything, it is fair to ask: What is a soundtrack album? Last year the sacred definitions of “film” and “television” were under assault from scholars, critics and upstart media providers. SCMS moved to change the name of its journal (causing some bemusement). A TV show was called a (great) film. And a (less-than-great) made-for-TV movie threatened the very idea of cinema. Yet through it all, soundtrack albums continued to refuse to acknowledge any difference between “film” and “TV.”

Second Verse, Same as the First

At the end of 2017, major film journals anointed Twin Peaks: The Return among the best, if not the best, film of the year. [2] And there was much gnashing of teeth. Rather than celebrating the text’s ascension to the mountaintop of transmedia [3], scholars fought over the text’s “home.” Twin Peaks’ cute marketing wisely taps into the work’s always fascinating internet presence and embraces the era of streaming media. There are also two distinct soundtrack albums (including a Target “exclusive”). Whatever the preferred label—auteur TV, “peak” TV, or film—Twin Peaks pedaled music using conventional methods.

The Netflix movie Bright was also a flashpoint in media circles. The critical drubbing at times felt like a defense of traditional (theater-based) cinema. Bright first entered popular culture through “innovative” marketing, and unsurprisingly, with the release of singles and an album. Netflix clearly regards soundtrack albums as a useful, even essential, tool in their empire. Like Amazon, Netflix is in the music business, but we knew that already. Bright, like Twin Peaks, is an (expensive) advertisement for music.

Spot the Soundtrack (Album)

Soundtrack albums ignore and extend well beyond the film-TV binary. And if soundtrack albums are at, or near, the heart of audio-visual media, the parameters of the category should be defined. We might, therefore, play a brief game of “spot the soundtrack album.”

I use the term “soundtrack album” here, as in my first Flow column, to designate a grouping of songs, whether collected on a physical medium or not. This phrase risks redundancy because the term “soundtrack” is often used to describe these objects. But “soundtrack” is used just as often to describe the audio portion of audio-visual media.

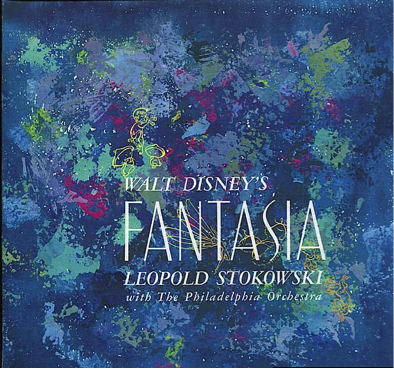

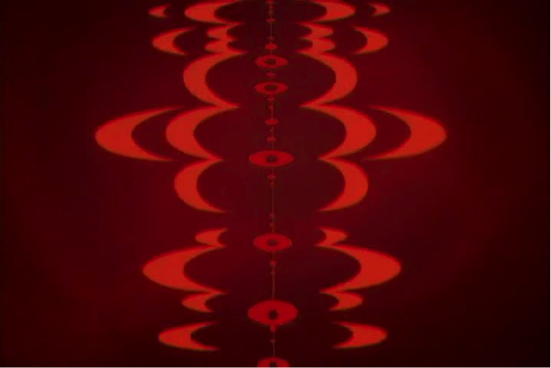

On the left is (one) soundtrack album for Disney’s Fantasia (1940), a film that strove to bring “classical” music to the masses by turning movie theatres into concert halls (that still showcased Mickey Mouse). On the right is the character “soundtrack” within the film, described as “shy” and at times looking very much like an optical soundtrack. Both of these can be called a soundtrack, but only one is a soundtrack album. The advantage of “soundtrack album” is to formally—but not permanently—separate these texts from the audio address of audio-visual media.

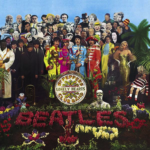

The 1978 Robert Stigwood production Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and its soundtrack album, directly feed into the belief that the Beatles’ 1967 album of the same name is the first “concept” record, or even itself a soundtrack album, rather than (merely) an intricately produced collection of songs without a unifying idea or sound. An essay accompanying the fiftieth anniversary edition of the album states: “If Revolver is like a photo album—fourteen exquisite, self-contained vignettes showcasing the talents of each Beatle in under three minutes each—Sgt. Pepper is like a film: not a passive record of life, but a moving picture of it.” [4]

The album on the right is clearly a soundtrack album. And a doozy. But might the film retroactively turn the Beatles’ release into a soundtrack album too?

On the left is the West Side Story (1961) film soundtrack album, while on the right is the play’s 1957 soundtrack album, more commonly called the “original cast recording.” Both of these are soundtrack albums, and both sold very well. The latter allows us to acknowledge the importance of theatre soundtrack albums and their importance to the growth of the long-playing album as a format. Soundtrack albums helped create the medium they are now asked to preserve.

By some accounts, cast albums—first Oklahoma! (as a set of 78 rpm discs and later an LP) and then My Fair Lady—dominated early album sales. These audio versions of Broadway shows allowed audiences physically and/or temporally separated from the New York City run to experience these works. When South Pacific (1958) and The Sound of Music (1965) each became the top-selling album a few years after release, the film soundtrack album symbolically and economically replaced the Broadway album as the default soundtrack album. Of course, Broadway soundtrack albums continue to deliver sound outside theatres.

There is one, or two, more variations on the term and concept of soundtrack album that deserve some brief discussion. The phrase “visual album” has seen a recent resurgence, most obviously in connection with work by Beyoncé, JAY-Z and Fergie. Using this term rejects the subordinate position that “soundtrack album” tends to impose on audio material vis-à-vis audio-visual media. This effort to rethink, and reframe, the relationship between these texts is fair and justified (if not exactly new). But “visual album” flirts with redundancy just as much as “soundtrack album” (see above where Revolver is labeled a photo album). And rather than signaling a different relationship between texts, it might simply reverse the hierarchy between audio-visual media and soundtrack album. At least it encourages a conscious address of terminology.

The “visual soundtrack” above is a fascinating iteration. Created for Japanese audiences (the subtitles are a feature and not a bug), the LaserDisc release joins new images with the show’s famous music. It is official but not undertaken by Twin Peaks’ creators. Unlike other “visual albums,” it appeared after, rather than alongside, the audio text. The work (re)visualizes the music, surveys the show’s locations, and functions as TV tourism (even revealing the inside of a certain train car).

What is a Soundtrack Album?

A workable definition of “soundtrack album” must encompass works connected to film, television, streaming content, video games, books, and perhaps even the diverse range of texts circulating as “visual albums.” A soundtrack album is not an adjunct text; a soundtrack album is a text whose relationship to one or more other texts is fluid and where meaning flows in all directions. These relationships are never simple.

For example, there are three Don Johnson texts called “Heartbeat”: a song, an album, and an album-length video. Which is the center? Johnny Thunders would likely vote for the song. [5] Others would probably favor whichever text they encountered first (a frequent concern in adaptation studies). [6]

Are these texts the soundtrack of Johnson’s career? (Kerouac may have one). Is the video a “visual album” or “visual soundtrack”? And does calling the album a soundtrack stifle Johnson’s vision or restrict our interpretive options? Not if we view soundtrack albums as always the center of their own universe of texts and whose meanings and relationships await consideration.

Image credits:

1. Twin Peaks: The Return soundtrack

2. Bright: The Album

3. Fantasia soundtrack

4. Author’s screengrab

5. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

6. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band soundtrack

7. West Side Story soundtrack

8. West Side Story (Original Broadway Cast)

9. Playlist for The Twin Peaks Visual Soundtrack

Please feel free to comment.

- Zach Fuller, “With Black Panther: The Album At Number One In The US, Are We Witnessing A Soundtrack Renaissance?” , February 20, 2018. [↩]

- Of course, the Twin Peaks property, long before it was rebooted / revived / picked-up by Showtime, already bridged the porous divide between film and television since it consisted of a TV series and a prequel film. Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) is also a hybrid text of material made for television and material made for cinema theaters. [↩]

- Just when you thought The Matrix texts required homework, welcome to Twin Peaks. To process The Return apparently required reading The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer and Twin Peaks: An Access Guide to the Town, screening Fire Walk with Me (1992) and studying that film’s extensive deleted scenes, and of course reading the two new David Frost books (The Secret History and The Final Dossier). The nostalgia for Twin Peaks season 1 is not unlike the nostalgia for the first Matrix film. Neither is an unreasonable response. [↩]

- Howard Goodall, “Sgt. Pepper’s Musical Revolution,” Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band 50th Anniversary Box Set (2017): 97-98. [↩]

- Cheetah Chrome, A Dead Boy’s Tale from the Front Lines of Punk Rock (Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2010): 307. [↩]

- Peter Brooker, “Postmodern Adaptation: Pastiche, Intertextuality and Re-functioning,” in The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen, Eds. Deborah Cartmell and Imelda Whelehan (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge UP, 2007): 107-120. [↩]

Great read but I have to point out a third Twin Peaks Season 3 soundtrack album: https://deanhurley.bandcamp.com/album/anthology-resource-vol-1

Oops. Of course. I own it.

Pingback: Soundtrack Album Fandom and Unofficial Releases Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University – Flow