The Homogenized Queerness of Historical Television

Britta Hanson / University of Texas at Austin

How much does historical representation matter? On television, it is in a grey area at best.[1] Although many historical series are conceived of as prestige productions, their fidelity to the eras they depict is hardly by-the-book.[2] In a much discussed, example, The Tudors decided that Henry VIII didn’t need to grow round as he aged. With the exception of the occasional diehard historian, though, most audience members don’t see significant harm in these changes – and perhaps rightly so. The setting, historical or present-day, is ultimately a stage on which the characters and stories play.

If we change the question to how much LGBT representation matters, though, the stakes are exponentially higher. In spite of increased numbers of LGBT characters on television overall, the quality and diversity of their representation remains spotty at best, with the Spring 2016 “Kill Your Gays” [[http://ew.com/article/2016/06/11/atx-bury-your-gays-trope-lexa-100/]] epidemic serving as just one recent example. [3]

It is at the intersection of historical and LGBT representation, then, that we find a curious (or, shall we say, queer) niche: same-sex-oriented characters in non-modern contexts.[4] While little explored, these kinds of representation are arguably even more important than contemporary portrayals of queer experiences.

Yes, portraying modern, everyday queer experiences has great socio-cultural importance. But it’s also important to remember that, historically, the nature of queer experiences have been an especially difficult to track. Across many periods and cultures, people who pursued same-sex attraction often faced dire ramifications for their actions, legal or otherwise. This illicit connotation means that, while historical accounts do exist for the eagle-eyed researcher to find, the archival record of queerness is often hidden from view.[5] By depicting queer figures in history, then, television has the power to break through this seeming invisibility, and give queerness a voice where many assume it had none.

These historical same-sex experiences, though, are far from equivalent to the present-day concept of homosexuality. Indeed, the Western concept of binary sexual orientations – i.e., of homosexuality and heterosexuality as mutually exclusive and immutable categories of personhood is of radically recent vintage.[6] And neither this nor any other unified definition of homosexuality has applied throughout history. Quite the opposite: the meaning and experience of same-sex desire has shifted radically across periods and cultures.

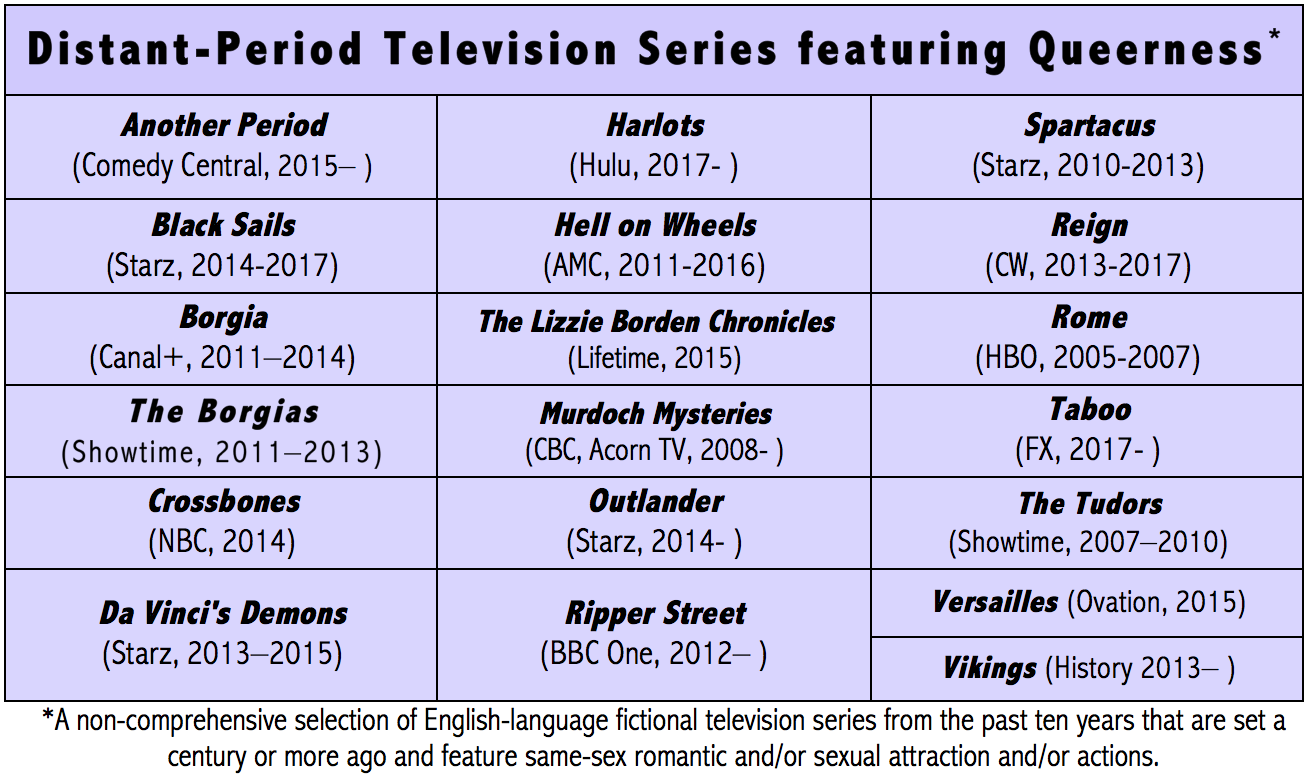

Yet many historical television series apply our contemporary understanding of gender and sex to their period, ignoring the ideas unique to that era and culture. This trend is most obvious on shows set in the distant past, beyond the easy recollection of our parents or grandparents. A sampling of such shows featuring queer experiences is in the chart below. By applying a homogenous, contemporary framework to the varied past, these series provide a misleading portrayal of the ever-shifting concept of sexuality in culture.

For example, The Borgias follows the titular clan’s schemes for ever-greater power across the Renaissance Italian city-states. Renaissance Italy was relatively tolerant of same-sex relations, generally speaking. Men often did not marry until their thirties, and then took brides barely in their teens. In this culture of bachelors, sexual relationships often formed between older and younger men.[7] The practice became so common that one reformer moaned that “[t]here is no distinction between the sexes or anything else anymore,” and “to Florence” was slang for sodomy in sixteenth-century Germany.[8]

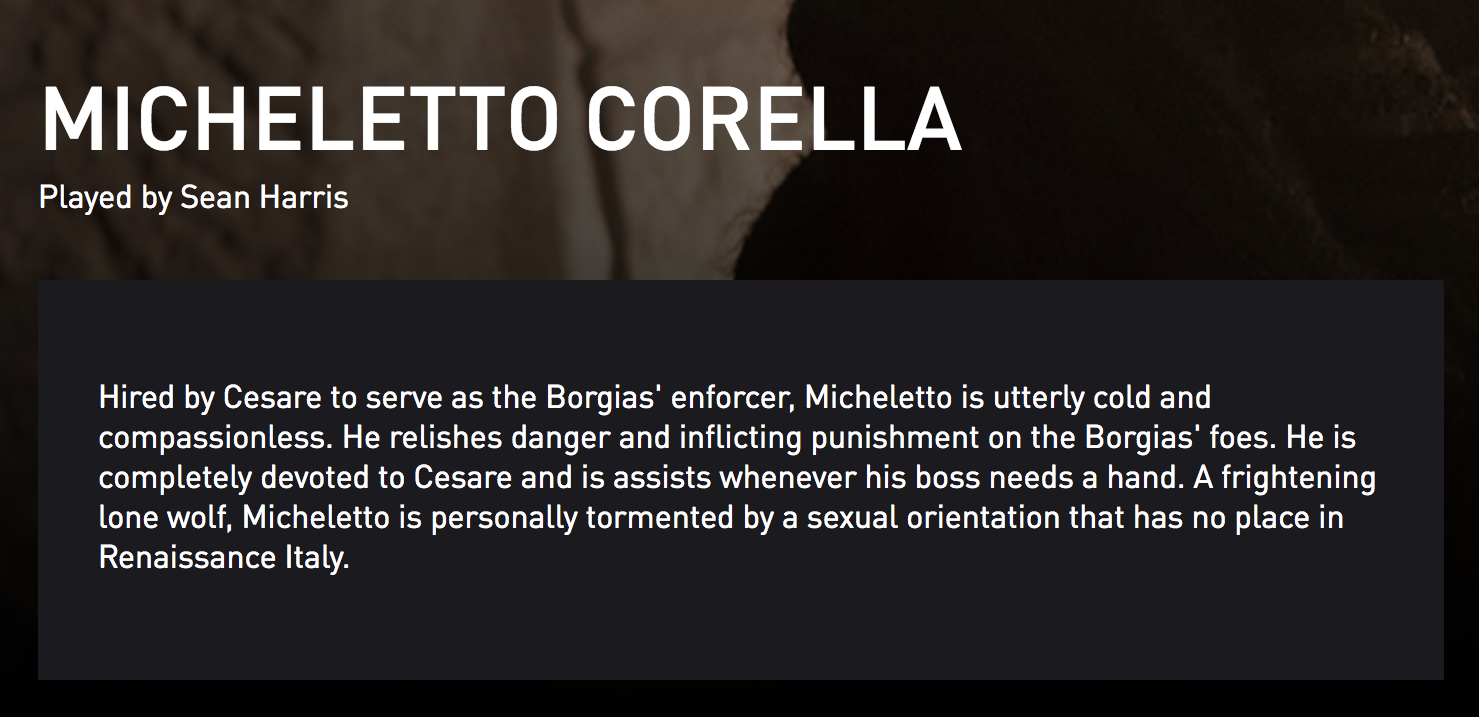

The Borgias does not reflect this historical reality, instead portraying a binary conception of sexual orientation, as well as an idea of undifferentiated intolerance of same-sex actions. Micheletto (Sean Harris), an assassin for the Borgias family, tells his lover Angelino (Darwin Shaw) that the latter’s impending marriage “will be a lie.” Angelino replies that he must proceed anyway, given the punishment for their relationship would be to be “disemboweled and burnt.”[9] What’s more, the show’s website describes Micheletto as having a “sexual orientation that has no place in Renaissance Italy.”

A similar transposition of contemporary ideas occurs on Reign this time to Elizabethan England and France. At this time, neither country thought of “homosexuals” as a defined minority (in fact, that term had yet to be invented).[10] That era of Christianity considered sex between members of the same sex sinful largely because it could not lead to reproduction. Thus “sodomy” was more closely linked to “debauchery” than “homosexuality.”[11] Yet on Reign, when Mary, Queen of Scots is told that her lady’s suitor prefers men “in bed,” she immediately understands this to mean that he is unfit to marry a woman. The lady in turn unequivocally rejects him, as she sees any romantic connection between them as impossible: “I’d be living a lie forever with no chance of happiness.”[12]

A more subtle, but still troubling, example occurs on Taboo, set in 1814 London. Georgian London was home to molly houses or clubs, where men met to make romantic connections as well as to cross-dress. At this time, “molly” meant an effeminate man, but did not necessarily connote same-sex interest.[13] It is significant for a practice so specific to a historical queer subculture to get representation on television.[14]

When Delaney (Tom Hardy) discovers Godfrey (Edward Hogg), a childhood acquaintance, at one such club, however, their conversation is still shaped by modern ideas of the closet and gay male identity. Delaney remarks that Godfrey “hasn’t changed” since they knew one another, and Godfrey replies that he was formerly in love with Delaney, a fact Delaney “of course” knew, and the experience of which was “torture…exquisite.”[15] Thus, Godfrey is not understood as merely effeminate, but as having always been imbued with gay male identity, a fact readily apparent to all around him. His association “straight” boys was torturous because crossing the divide between the two categories was wholly impossible.

While these differences in presentation versus history seem more extreme in distant-period shows, they are still significant in more recent-set historical series.[16] The Halcyon is set in London during the Blitz, a city and time with a fast-developing queer subculture, but which still did not entirely sentence “gay” and “straight” persons to opposite sides of the fence.[17] On this show, when the clandestine affair between a well-to-do man and a waiter at his family’s elite hotel is discovered, their discoverer states that, “in my experience, a man doesn’t choose who he falls in love with.”[18] It is perhaps possible that he would have turned a blind eye. It is very unlikely, though, that he would have used the twenty-first century “love is love” and “born this way” rhetorics, and that the couple would have readily understood such language, thus naturalizing it as part of that historical environment.

At first glance, this argument may seem an inconsequential quibble over historical accuracy, akin to the squabbles over Mad Men’s typewriters. However, these representations have much more dire effects than a Remington.[19].

First and foremost, these representations homogenize queerness. Queer characters are presented as equivalent to modern homosexuals, with little room spared for bisexuality or any other form of queerness. The place of same-sex experiences within culture is shown as entirely undifferentiated, essentially one long slog of oppression and tragedy. While different types of oppression were the reality in many eras and places, leveling all historical periods minimizes the unique struggles of those who lived through those eras. It is a pity to obscure the multiplicity of ways in which same-sex experiences were navigated in specific environments, and how queer people carved out their own subcultures.

Furthermore, by creating this faux-modern, unvarying slate of queer characters and experiences, these shows frequently fall back on today’s standard queer tropes, most of which reinforce negative stereotypes. The “tragic queer” and “kill your gays” appear constantly: i.e., queer sexuality is a burden that causes personal unhappiness, misfortune, and even death. The seemingly-accepting man on The Halcyon quickly resorts to blackmail. On The Borgias, Micheletto discovers his new lover Pascal (Charlie Carrick) has been selling his secrets. The Borgias order Micheletto to kill Pascal, after which Micheletto flees the city in grief – and permanently exits the show.[20] Men seeking sex with other men are shown as predators and rapists (Outlander) or straight men in a easily-dismissible, one-time “experiment” out of “curiosity” (Da Vinci’s Demons).[21]

This homogenizing trend is significant beyond the confines of historical series. Rather, it points the broader ability of media to win praise for fleeting “exclusive gay moments,” no matter how brief or problematic.[22] The question should not merely be quantity of representation, or even quality. As trite is may sound, it is about equality: queer characters should be constructed with equal care as their straight counterparts. Bickering about historical television may seem silly. But given that these shows’ audiences care enough to rage over Henry VIII’s haircut, they must take a stand on an issue with much higher stakes, and demand halfway-decent historical queer representation.

Image Credits:

1. The Borgias (Showtime, 2011-2013), Season 3 Episode 7 (author’s screengrab).

2. Chart created by author.

3. The Borgias official website (author’s screengrab).

4. Mary, Queen of Scots on Reign (The CW, 2013-2017), Season 1, Episode 15 (author’s screengrab).

5. Godfrey and Delaney on Taboo, Season 1, Episode 3.

Please feel free to comment.

- Aspects of this topic were originally presented at the Film and History conference in Madison, Wisconsin and QGRAD at UCLA. My thanks to all those who gave feedback there and elsewhere. [↩]

- As one measure of prestige, 18 of 32 Emmy nominees for the Drama Series Emmy in the past five years (2012-2016). [↩]

- 4.8% of series regulars in 2016-2017 were LGBT, a 60.4% increase over 2011-2012, according TO GLAAD’s Where We Are on TV reports. [↩]

- Given the brevity of this article, and the paucity of representations in that category, I will not be discussing transgender experiences, although I wish to stress the importance of and need for such representations on the air. [↩]

- See the revised preface and introduction of Jonathan Ned Katz’s landmark collection of primary sources, Gay American History (New York: Meridian, rev. ed. 1992) for further discussion of the trials of writing queer history, as well as that history’s diversity. [↩]

- Most historians of sexuality more or less support Foucault’s argument that, in the Western context, the contemporary understanding of a “homosexual” as a “species” of person did not begin to take shape until the nineteenth century. See Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Pantheon, 1976), 43. [↩]

- See here and Laura J. McGough, Gender, Sexuality, and Syphilis in Early Modern Venice: Disease that Came to Stay (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 27. [↩]

- Judith C. Brown and Robert C. Davis, Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy (New York: Routledge, 1998), 150; Katherine Crawford, The Sexual Culture of the French Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010), 11. [↩]

- The Borgias, Season 2, Episode 5. [↩]

- Alan Bray, “Homosexuality and the Signs of Male Friendship in Elizabethan England,” History Workshop, 29 (1990), 1-19. [↩]

- See N.S. Davidson, “Sex, Religion, and the Law,” in Sodomy in Early Modern Europe Tom Betteridge, ed., Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2002. [↩]

- Reign, Season 1, Episode 15. [↩]

- See Morris B. Kaplan, Sodom on the Thames: Sex, Love, and Scandal in Wilde Times (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), and Charles Upchurch, “Liberal Exclusions and Sex between Men in the Modern Era: Speculations on a Framework,” Journal of the History of Sexuality, 19.3 (2010), 409-431. [↩]

- Molly houses have also recently appeared on Ripper Street and Dracula. [↩]

- Taboo, Season 1, Episode 3. [↩]

- See here for a list of twentieth-century period programs featuring queer experiences. [↩]

- For more on the historically distinct queer subculture of early-twentieth-century London, see these books. [↩]

- The Halcyon, Series 1, Episode 6. [↩]

- The intention of the writers in making these choices is too big a question for this study, although some preliminary thoughts on the matter can be seen here for further consideration of this issue. [↩]

- The Borgias, Season 3, Episode 9. [↩]

- On Outlander, Captain Randall rapes Jamie in the first season, and the Duke of Sandringham is essentially a villain, revealed to have been secretly orchestrating the misfortunes of the protagonists. Granted, the author of the original book series, has described Randall as a “pervert” and “sadist” as opposed to having a sexual preference, but this distinction is not clear on the show itself. And despite historians’ near-certainty of Da Vinci’s sexual preference for men, on Da Vinci’s Demons, he prefers to sleep with women, with his one-time male-fling a failed experiment. [↩]

- Queer audiences also fall into this trap, such as when the queer media outlet NewNowNext.com (formerly AfterElton.com, now owned by the queer-focused Logo channel) celebrated the scene of queer erasure cited above in Da Vinci’s Demons, for despite the damning context, it contains a kiss between men. [↩]

I found this piece insightful and still depressingly relevant. I was drawn to two of your points in particular, one being these portrayals that can be marked by “modern ideas of the closet,” and the second being how limiting of actual historical queer life and culture these portrayals can be.

The idea that historical television marks queer characters with modern concepts of the closet is evident, and yet I would argue, it relies on concepts of the closet of an era just past. The required suppression of homosexual identity marked by these historical shows is more akin to, say, the 1950s in which an out life was even more heavily penalized. Not only does this then feed into the ongoing issue in television of the tragic queer and the “bury your gays” trope, it also feeds into a post-closet mentality. By making queer life something so recognizably illicit and easy to understand in these terms in historical television, it sets a framework which asserts that not only was this how it was in the past, but these issues regarding visibility and acceptance do not play out in the modern world. It creates a spectacle in which the audience is meant to marvel at the rigid oppression of the past and forget that any issues exist in modern media and culture.

To speak to your point about how reductionist and incorrect this view is of actual historical queer life is and your question of how much historical representation on television matters, I would argue it matters a great deal. As you detail, these shows obfuscate realities of queer history in favor of a modern tragic gay narrative. By homogenizing queerness in history as you say, little room is left on television for a more nuanced or diverse portrayals. For example, as you explain, these historical portrayals lack an exploration of “bisexuality or any other form of queerness,” in eras when such firm and stigmatized gay/straight definitions may have been lacking. This is a shame because they certainly exist now and persist in modern television. I can think of several shows which could be said to represent bisexual characters, and yet almost none actually utter the word “bisexual.” Contemporary portrayals of modern queerness seem to shy away from diverse forms of queer identity and experience. Though I saw only the first two seasons, Orange is the New Black comes to mind as a show which attempts to portray diverse queer experiences, and yet despite the lead character’s relationships with both men and women, her sexuality is constantly defined by whether or not she is a lesbian, or was a lesbian, or has become one again. Therefore sexuality is being defined still in diametrically opposed ideas of gay vs. straight. While it is not for me to judge what queer identity someone aligns with, this example represents an wider pattern of avoiding addressing queerness that falls outside of the gay/straight paradigm. Given that this is a major feature of television representation of modern queerness, it seems an even greater shame that, in historical contexts in which such rigid definitions of queer identity might not have been the norm, these more nuanced frameworks are not portrayed as such on television. Historical queer representation on television is therefore a lost opportunity to examine other frameworks and dynamics than those of modern media.

It’s lazy to say Outlander only repredents homosexuals as rapists as John Grey is an excellent rep. Sometimes gay dudes are rapists just like plenty of straight dudes in Outlander.