Of Nasty, Unlikeable Women: Veep and the Comedic Female Anti-Hero

Shweta Khilnani / Maitreyi College, University of Delhi

In a moment of candor during an interview in March 2016, Tina Fey admitted that “it’s a terrible time” for women in comedy. She argued that “boys are still getting more money for a lot of garbage while the ladies are hustling and doing amazing work for less.”1 A couple of years before this interview, Anna Gunn, who played Skyler White on Breaking Bad, expressed her bewilderment on being the subject of extreme vitriol from viewers even as they continued to root for the male protagonist of the show, Walter White, despite his many moral failings.2 Such instances make one wonder: does the audience still approach women characters with a certain sense of gendered prejudice?

Television has given us several groundbreaking women characters starting from Mary Richards all the way to Carrie Bradshaw, Ally McBeal and Liz Lemon. Unsurprisingly, these characters acquired a huge fan following and have been regarded as modern female role models. However, what about a female character who isn’t exactly a paragon of success or fortitude? Is there space for female characters who aren’t designed to serve as feminist icons? With a focus on the character of Selina Meyer from Veep, I intend to study the emergence of a female comedic anti-hero who engages in a repeated “performance of failure.”

As a show that features a female character in a prominent political position, Veep joins the list of others like Commander-in-Chief, Madame Secretary, State of Affairs, Scandal and Parks and Recreation. Veep narrates the many misadventures of Selina Meyer, the Vice President of the United States of America, played to perfection by Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Armando Iannucci, the creator of the show, said that the choice of a female Vice President was dictated by the need to avoid any comparisons to real Vice Presidents. He says, “We don’t want people to think, oh, well this is Joe Biden or this is Dick Cheney or this is Al Gore. We decided, let’s think forward rather than backward—if we made it a woman we are sort of saying, she’s her own person.”3

Having said as much, the decision to cast a female Vice President permeates the comedy at several levels. There are multiple instances where Meyer’s gender makes its presence felt in the show – she keeps moving in and out of her heels according to the political stature of the official who enters her office, she has to worry about a possible pregnancy and the appearance of bags under her eyes and is deeply disturbed when she comes to know that one of her own staff members has been calling her the “C” word. When Meyer is on the verge of defeat in the Presidential Elections, she tells Amy Brookheimer “my political window slams shut the second I can’t wear sleeveless dresses.” Clearly, both the showrunners and the fictional character of Selina Meyer are all too aware of the gendered discourse around a woman in a position of power.

The character of Selina Meyer is peculiarly self-indulgent and narcissistic; she is often inept in her professional capacity, is given to extreme profanity and is viciously critical of her daughter Catherine’s actions. David Renshaw from The Guardian defines Meyer’s character as a “perfect combination of ineptness and amorality.”4 This sets her in sharp contrast with someone like Leslie Knope, a perky, enthusiastic and devoted employee of the Parks and Recreation department of the fictional town of Pawnee in Parks and Recreation. This show, labeled as a “comedy of super niceness,” presents Knope as a relentless idealist whose office features a “wall of inspirational women” adorned by photos of Hillary Clinton, Condoleezza Rice and Nancy Pelosi.5 Owing to her fiercely loyal and supportive friendship with Ann Perkins and her passionate commitment towards her work and the town of Pawnee, Knope’s character has been celebrated as a sincere feminist icon.

As opposed to this waffle-loving, saccharine optimist who regularly comes up with gems like “uteruses before duderuses”, we have Selina Meyer, a conceited, farcical realist from Washington whose mouth is laced with some of the most brutal and spiteful (also innovative) profanities one will ever hear. This is not to say that Meyer doesn’t have her moments of personal earnestness or professional success. As the show progresses, she becomes more involved in foreign policy decisions and she does get an automatic promotion when the President resigns. Yet, more often than not, she, along with her staff members, finds herself in the middle of some hopelessly mishandled situation, the multiple instances of fudged/lost public speeches being testament to that fact.

By giving us a female Vice President who is liable to error and even buffoonery at times, how does Veep weigh into the gendered discourse surrounding women in political office, especially at a time when a female candidate lost the recent Presidential elections? Is it relevant that Meyer doesn’t exactly lead by example or champion the cause of a female President? Before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s not forget that this is a comedy show in question and Meyer isn’t the only incompetent member of the White House. In fact, the entire premise of the political satire is to expose the ineptitude and coarseness of the world of politics. Keeping that in mind, how does one negotiate the immensely flawed character of Selina Meyer?

Interestingly enough, the character of the flawed male hero has earned both popularity and critical acclaim on television screens in recent years. Beneath the suave veneer of characters like Tony Soprano from The Sopranos, Walter White from Breaking Bad and Don Draper from Mad Men, lurks a more sinister side of their personality responsible for their morally ambiguous behavior. While the examples quoted above hail from the genre of drama or what is now being called “quality television,” comedy has its fair share of male anti-heroes as well, such as Gob Bluth from Arrested Development and Larry David from Curb Your Enthusiasm.

The category of the female anti-hero has always been fraught with tension. When a female character displays the same kind of moral ambiguity commonly associated with male anti-heroes, as in the case of Skyler White from Breaking Bad, it evokes hostility from the audience instead of recognition or at times, emulation. Alternatively, a female anti-hero is often unapologetically ambitious and is willing to transcend moral boundaries to achieve her goals. Ultimately, this unbridled ambition becomes her redeeming quality. But what about the category of the female comedic anti-hero – a character who is crude, unpleasant and innately unlikeable? The creator of The Mindy Project, Mindy Kaling, stated in a conversation at the New Yorker Festival that her idea for Mindy Lahiri wasn’t a spunky role model like Mary Tyler Moore. She goes on to say, “I don’t want kids to want to be Mindy Lahiri when they grow up.”6

In a similar vein, perhaps the character of Selina Meyer isn’t designed as a feminist role model at all. Seldom do things work out successfully for her. In fact, as the audience, we are always prepared for a massive professional or personal debacle. The threat of failure is always a concrete possibility for Meyer and the people she surrounds herself with. One can even argue that her character engages in a “performance of failure,” where the degree of failure can range from a harmless gaffe to a serious political disaster. Yet, significantly, this performance of failure is not sublimated to her gender. As a woman in office, she has the liberty to fail repeatedly without inviting gendered criticism. One failure at a time, the audience slowly learns to embrace Meyer’s character with all her narcissism and impropriety.

This is symptomatic of the space created for a new brand of female characters, the kind who are not bowed down by the expectations of being a source of inspiration for other women. Ironically enough, the true success of Veep (in terms of the unapologetic representation of its flawed female protagonist) lies in Meyer’s status as a failed character.

The fact that viewers are just as receptive to an unbelievably earnest character like Leslie Knope as they are to a profoundly apathetic one like Selina Meyer hints towards the broadening horizons for gender roles in comedy.

Perhaps, it’s not so terrible a time for women in comedy after all.

Please feel free to comment.

Image Credits:

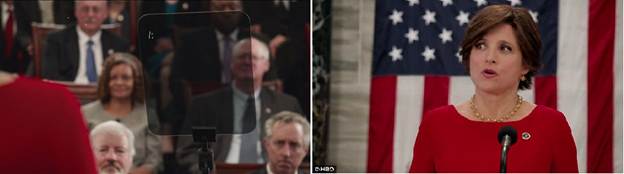

1. Selena’s Performance of Failure

2. Lesley Knope

3. Teleprompter Goes Blank

- Schilling, Mary Kaye. “Tina Fey Goes to War.” Town & Country. March 1, 2016. [↩]

- Gunn, Anna. “I Have a Character Issue.” New York Times. August 23, 2013. [↩]

- Bennett, Laura. “The Sneaky Feminism of ‘Veep’.” New Republic. April 28, 2013. [↩]

- Renshaw, David. “Veep – box set review.” The Guardian. August 08, 2013. [↩]

- Paskin, Willa. “Parks and Recreation and the Comedy of Super Niceness.” Vulture. March 24, 2011. [↩]

- Nussbaum, Emily. “The Female Bad Fan.” The New Yorker. October 17, 2014. [↩]

I just finished #GIRLBOSS, which has another flawed female protagonist. As I watched it I thought of Selina Meyer and Leslie Knope and how this show isn’t necessarily producing a female role model, and if that is even the point. It’s even stranger that the Sophia character in #GIRLBOSS is based on a real woman – one that even helped produce the show. Thanks for a great read!

Hi Caroline!

As you pointed out, a number of television shows now feature a flawed female protagonist. It would be interesting to view Girlboss within that paradigm.

Thanks for the suggestion!

I had another comedic female antihero in mind, Deandra “Dee” Reynolds (Kaitlin Olson) from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia on FX. She is not only flawed, she is narcissistic and hideously vulgar (for as vulgar as you can be on FX) such as Selina Meyer however, she is in no position of power. Dee is desperate for acceptance and attention from her fellow members of the “gang,” which includes her wicked twin brother Dennis (Glenn Howerton), his two friends Mac (Rob McElhenney) and Charlie (Charlie Day), and eventually Frank (Danny DeVito), her non-biological heinous father. As raging alcoholics, they own a bar, “Paddy’s Pub” where in one episode, Dennis relishes in the fact that Dee is not an owner, makes less than minimum wage, and is constantly berated by the group. As a raunchy controversial comedy exploring numerous topics, it’s hilarious in its improvisational technique and critiques on racial and gender politics, economics and financial crises, pop culture etc. We don’t mind when the gang tells Dee she looks like a bird in every episode or that she is gruesomely unattractive because we realize this is simply untrue. Yet, we laugh at the juvenile “Big Bird” jokes due to her tall and thin stature despite her runway model body shape. I realize that these men make Seinfeld, Kramer, and George look like angels but that is what I come back for, to see how they keep Dee at an arm’s length as she “noses her way into everything.”

It is also pleasurable when she pairs up with one of the members (Dennis, Mac, Charlie, Frank) for a scheme as they tend to split up depending on their ridiculous idea or odd activity. These are the times where Dee is “included” and indeed, part of the gang rather than an undesired presence. She is a spitfire, crude, and unapologetic in her antics manifested from her lack of upbringing and subject to verbal abuse since her childhood. Though these stories sound tragic and upsetting, the show broadens the comedic spectacle of women in the form of satire. The gendered tropes of women being subordinate to men is at the forefront but, the exaggerated scenes are so dysfunctional that we can sit back and laugh. Like Meyer, we aren’t critical of Dee’s failed attempts to become an actress or her desperation for acceptance; she is, also, a new brand of the female character.