The Mary Tyler Moore Show, American Television, and the Slow Pace of Social Change

Elana Levine / University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee

There are few better sites through which to understand the incremental nature of social change than American television. Because the medium has been structured to earn profits for corporations and to resonate with a diverse public, it necessarily wavers between minimizing risk and engaging with the emergent, and potentially disruptive, interests of everyday people. In the present, it is difficult to see the ways these tensions can result in the small and often partial steps that might eventually build to progressive social change. Such developments are more visible from the perspective of history.

Both The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-77) and its eponymous co-owner/star were linchpins of social change in terms of television’s representation of women, and of real-world changes in beliefs about and experiences of gender. By representing women’s role in both public and private spheres differently from most instances of television’s past, The MTM Show and Moore herself set the tone for what might be possible in TV depictions of women in the years to come. These possibilities allowed for progressive change in some respects, but linked those changes to conventions of femininity that would moderate their impact; there are no revolutions when it comes to American television.

The social intervention of The MTM Show was a result of the many forces that combine to create TV and that shape its resonance. As a range of scholars have documented, the show was in part an outcome of the move by the TV industry and its advertisers to target young, upscale viewers in urban centers rather than the broad mass assumed to be the inevitable audiences of the network era. As part of the “turn to relevance,” The MTM Show had permission to speak to contemporary social changes, in this case new ideas about women’s roles. It also was able to benefit from the freedoms of independent program production. The Financial Interest and Syndication Rules gave a company like MTM Enterprises, unaffiliated with a major studio or network, the opportunity to become financially solvent while licensing its shows to the networks. [1] (The company even commented on its independence by substituting a meowing cat in its logo for the roaring lion in the MGM logo it referenced.) The production was hardly free from the many constraints of the American TV business, but it deserves some credit for its ability to introduce new dimensions of women’s experience to prime time, in part due to the presence of “feminist conscience” Treva Silverman on the show’s writing staff, one of the few women in such positions at the time. [2]

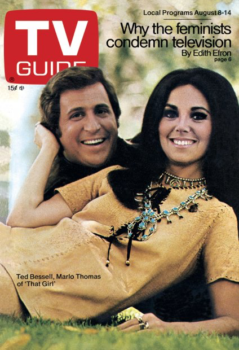

These conditions were paired with the advertising industry’s growing realization that changes in women’s roles encouraged by the Women’s Liberation Movement meant a re-evaluation of the traditional ways products were pitched to women. Paired with an array of protests over and investigations into media treatments of women, the different approach The MTM Show offered was an ideal fit for its cultural moment, a moment when a mainstream publication like TV Guide sought to explain, “Why the Feminists Condemn Television.” [3] Although US network prime time had seen women leads of sitcoms in the past, those women were typically contained by their domestic roles (I Love Lucy, Bewitched) or, like TV Guide’s cover girl, Marlo Thomas’ Anne Marie of That Girl, were occasionally allowed to be single and pursuing a career as long as they were more actively pursuing marriage.

The MTM Show’s protagonist, Mary Richards, was in her early thirties, single, and fresh off a break-up, a choice different from the original conception of the character as a divorcée, to which CBS had balked. Moving to the “big city” of Minneapolis and pursuing a career in TV news, Mary is hired by her curmudgeonly, sexist boss, Lou Grant, as an associate producer, a more impressive title for a lower salary than the job for which she had applied. Between her “family” of female neighbors in her new apartment and the workplace family to which she quickly acclimates, Mary becomes the caring, moral center of her communities, the “Mom” to those around her. Multiple critics have analyzed this representation, largely agreeing that the character’s independence and status both in her career and as a (somewhat ambiguously depicted) sexually active single woman amounted to a “compromised and contradictory feminism.” [4] Mary could be the “New Woman” advertisers believed the changing society was calling for, but the potential disruptiveness of this identity could be tempered by her “‘girl-next-door’ sweetness.” [5]

Crucial to this precarious position was the star image of Mary Tyler Moore herself. She was seen as an appealing figure to both men and women. As one critic wrote of her, and of Mary Richards, with whom she was conflated, “Men, whose taste in women runs from Tammy Wynette to Gloria Steinem, think she would make the perfect girlfriend. Women like the fact that she’s the star without being a sex queen or a loser.” [6] The reference to Steinem here is crucial, for Steinem shared the Marys’ conventional physical attractiveness while nonetheless reading as threatening to the status quo in her feminist activism. Both Marys could seem amenable to a (moderate) Women’s Liberation platform but without the threat that an overt activist such as Steinem posed. Indeed. CBS executive Perry Lafferty noted of Moore, “I think it’s her vulnerability that makes her particularly appealing . . . she’s beautiful and all that without being threatening.” [7]

The popularity of The MTM Show led to spin-off series, a number of ultimately failed imitators, and more durable successors, including Maude, One Day at a Time, and Alice, and all of which featured unconventional women leads — an older, married woman who espoused explicitly liberal and feminist views; a divorceé; and a widow raising a son. That Bea Arthur portrayed Maude made her different from most female sitcom leads but also permitted her politically activist stances. Her deeper voice, grayer hair, and larger bodily frame than a “sweetheart” star like Moore kept conventionally attractive heterosexual femininity from being too closely associated with feminism proper.

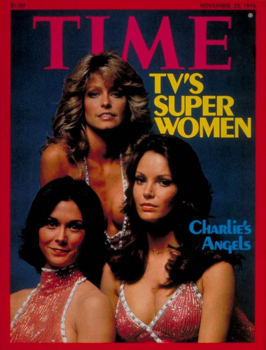

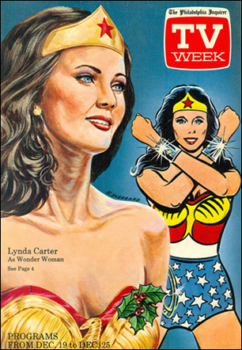

Indeed, American prime time television of the 1970s would shift toward action-adventure series with “sex symbol” female leads as its primary means of pairing conventionally valued forms of femininity with gestures toward feminism. In programs such as Charlie’s Angels and Wonder Woman, sexy young women took on duties like crime fighting, typically associated with men, sometimes in the name of women’s rights. But the assurances these programs offered of their heroines’ status as objects of desire helped these versions of the New Woman follow in the path of The MTM Show in the limited nature of their gestures toward change. The types of women such series depicted, and the generic constraints within which they operated, differed from The MTM Show. But their ultimate contribution to the medium’s participation in processes of social change was much the same.

The incremental and compromised progress in representations of women’s changing status in 1970s television was initiated and modeled by The MTM Show. The program, its star, and its viewership deserve kudos for this intervention; the economic, cultural, and political structures within which they emerged deserve our ongoing critique.

Image Credits:

1. Ed Asner and Mary Tyler Moore on The MTM Show

2. Marlo Thomas’ Anne Marie of That Girl

3. Mary Richards interviewing with Lou Grant on The MTM Show

4. Mary Richards

5. Gloria Steinem

6. Bea Arthur as Maude Findlay

7. Bonnie Franklin as Ann Romano

8. Linda Lavin as Alice Hyatt

9. Time cover of Charlie’s Angels

10. TV Week cover of Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman

Please feel free to comment.

- Jane Feuer, Paul Kerr, and Tise Vahimagi, MTM: “Quality Television” (London: BFI Pub, 1984). Todd Gitlin, Inside Prime Time (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983). Aniko Bodroghkozy, Groove Tube: Sixties Television and the Youth Rebellion (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2001). [↩]

- On Silverman’s role, see also Jennifer Keishin Armstrong, Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted: And All the Brilliant Minds Who Made The Mary Tyler Moore Show a Classic (Simon and Schuster, 2013). [↩]

- Edith Efron, “Is Television Making a Mockery of the American Woman?” TV Guide Aug. 8, 1970, 8. For more discussion of this cultural context, see Elana Levine, Wallowing in Sex : The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 128-130. [↩]

- Bonnie J. Dow, Prime-Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement since 1970 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 51. [↩]

- Ella Taylor, Prime-Time Families: Television Culture in Postwar America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 124. [↩]

- T. Johnston, “Why 30 Million Are Mad About Mary,” New York Times Magazine April 7, 1974, 96. [↩]

- Ibid., 30. [↩]

Thanks for sharing all this information.

It really helpful for me.I am also fond of super women series.

Please share more this type of information.