A Part and Apart: Hawaii and Domestic Satellite Broadcasting, 1967-1971

Selena Dickey / University of Texas Austin

In the “International” section of Broadcasting’s July 24th, 1967 issue, the industry trade journal reported the blast off of “A second synchronous Pacific communications satellite…a twin to the present Intelsat II satellite now providing 24-hour commercial service between the U.S. mainland and Hawaii, Australia, Japan, Philippines, Thailand.” [1 ]

In this nearly unnoticeable notice, Broadcasting alerted readers of the most recent step in satellite communications: with a second successful launch, engineers had proven their satellites could achieve and maintain geostationary orbit (that is, reaching an altitude of approximately 22,230 miles and moving at the same speed and rotational direction as Earth so that it stays in place over a single location). But yet subtly, this small announcement also shows how Hawaii is rhetorically configured as a part of and apart from the United States: though the 50th state in the Union, it is lumped together here with various Pacific island nation-states, marking it as not really domestic but, instead, as the section title reminds us, “international.”

The a part/apart-ness of Hawaii is nothing new. Many have looked at the pop culture representations of the island state, from tourism and airline campaigns showcasing the wahines with never-ending supplies of leis to the films of Elvis and Gidget hip-thrusting and surfing across the sandy beaches to the television shows featuring McGarrett and Magnum P.I. chasing criminals through the palm trees. All of these images have created a myth of Hawaii, an escapist’s multicultural utopia so utterly different from the mainland and yet so a part of it that, unlike Australia, Japan, the Philippines or Thailand, no passport is required.

What makes Broadcasting’s coverage different, however, is how its rhetoric configures Hawaii as a part/apart in a discussion of off-screen processes. Similar to the images of island exoticism that filled television and cinema screens, here the industry discourse surrounding the role of developing satellite technology also blurs Hawaii’s connection to the mainland and blends it with the foreign. That both onscreen and off-screen logics function in this way is significant. Both reveal how ideology operates not only within visual discourse but also within industry, policy and technology discourses. In other words, analyzing hula girl and tiki hut tropes is important, but it isn’t the whole luau.

For instance, other industry trade journals focusing on the novelty of satellite transmission also configured Hawaii in rather ambiguous terms. As a Variety article covering the sat-casting of the 1968 Presidential election put it,

[T]here is no reason why foreigners can’t see U.S. election returns live… With foreign newsman commenting on the pictures relayed by pool cameras, 18 1/2 hours of coverage were arranged for Europe and 9 hours and 20 minutes for Hawaii, 2 hours and 25 minutes for Australia, 6 hours and 30 minutes to Japan and two hours to the Philippines. [2 ]

Clearly, one of these things is not like the others.

Hawaii is, once again, slipped into a list of foreign regions and countries, its status as a U.S. state overlooked, reconfigured as a foreign body vying for satellite transmission time.

Even though the number of Broadcasting and Variety articles covering satellite technology and its connection to Hawaii is limited (approximately 30 stories from 1966-1971, the era when television broadcasters first began using satellite transmission), the rhetorical maneuvers and slippages of these longstanding trade journals, subtle as they may be, reveal how the industry conceptualized the island state at a key moment of telecommunication development: Hawaii as Other, as foreign. And this, paired with the findings others have made about onscreen representations of Hawaii, only further reinforces how Hawaii’s identity has been shaped and deployed in certain ways—ways often laden with explicit and implicit power dynamics. If evidence of this can be found in such a small sliver of writing on the development of satellite technology in this brief moment of history, how many other off-screen contexts have, over time, merged and mixed to shape the popular mythology of Hawaii?

For broadcasting industry insiders (network executives, affiliate station general managers, advertising and marketing firms, policy makers, etc.) reading these stories in the late 60s and early 70s, Broadcasting and Variety‘s rhetorical strategy of “othering” Hawaii had real world effects. Satellite technology was new; the role these key stakeholders would play in its development was still undecided; and the way these publications framed the issue within their pages—Hawaii not as a state but as a foreign market—influenced programming, advertising, and telecommunication policy decisions.

These decisions then rippled out to viewers and the general public, shaping their access and exposure to programming. That Hawaiians glimpsed the results of the 1968 Presidential election through the same satellite feed as Europeans and Australians, for example, marks their television experience of this event as significantly different from that experienced by Americans in the continental United States. Sure, Hawaiians were a part of the election—they voted in it, after all—but so too were they excluded from it, receiving national election coverage on an international satellite feed. Put another way, Hawaiians were a part of the mainland, exercising their voting rights as American citizens, and yet apart from the nation’s televisual “flow.” The consequences of this ambiguous—and uneven—televisual relationship with the mainland are complex and the subject of my ongoing research, but what can be said here is that, in the three-network era, access to and participation in a common national television “cultural forum” wasn’t so common, or even so national.

Looking at the ways off-screen practices shape regional identity has gained traction in television studies, with Victoria E. Johnson’s, Steven D. Classen’s, Yeidy Rivero’s, and Myles McNutt’s work particularly standing out. All take into account different elements, from policy to production to local politics, and each considers the ways those elements—operating beyond the frame of yet shaping what appears on a television screen—nuance and reshape our understandings of regional identity. Similarly, Broadcasting and Variety‘s coverage of newly developing satellite technology and its effect on Hawaiian identity reminds us that not only are there other regions still left to explore but also other off-screen practices to examine. It reminds us that to conceive of a homogenous televisual flow, of unhindered participation in a national television cultural forum, fails to consider the unique position Hawaii occupied during this particular historical moment and opens up the need for further investigations into the way region shapes understandings of technology, television, and culture, and vice versa.

Image Credits

1. Engineers Ready the Intelsat Satellite

2. Sat-Casting the 1968 Election Results, Broadcasting 77, no. 8 (1969): 32.

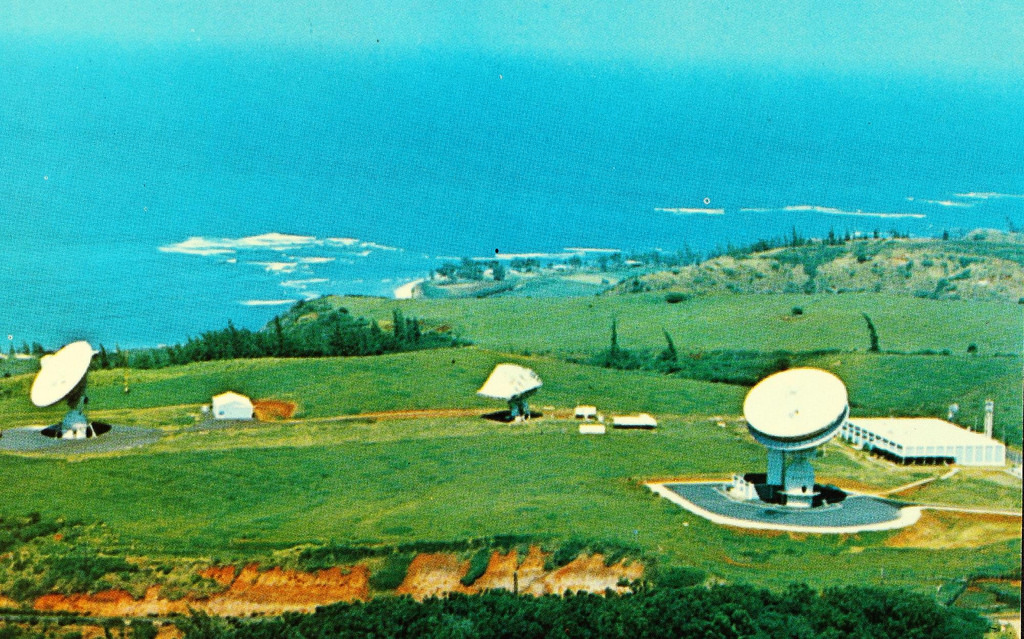

3. Paumalu Earth Station, Hawaii’s Satellite Access Ground Station

Please feel free to comment.

good night images