A Girl Divided: the Fragmented Shōjo in Perfect Blue

Dylan Levy / University of Texas at Austin

In Satoshi Kon’s debut animated film, Perfect Blue (1997), 21 year-old Mima Kirigoe quits her career as a pop-idol singer with the group Cham to pursue her newfound dream as a respectable television actress. Yet Mima’s transition does not suit some of her fans, particularly an overly obsessed young male that goes by the alias Me-mania. Me-mania desperately wants to preserve Mima’s pop-idol image by blogging on a self-made website called “Mima’s Room” under the assumed identity of Mima’s pop-idol persona. As Me-mania discredits Mima the actress as the “true” version of Mima, and as Mima herself checks the website more and more, she begins losing sense of her identity and gradually descends into delirium; the more she checks the website, the more confused and fearful she becomes by the presence of a supposedly “other” Mima.

Part of why Perfect Blue is considered a horror film is because of its twist on the traditional shōjo (Japanese young girl) character. The film addresses and subverts traditions of the shōjo image, positioning the characters Mima and her alter-ego, pop-idol Mima, as fragmented entities of the shōjo. My argument is that, in the words of Thomas Lamarre, Perfect Blue “play[s] with genre” by “play[ing] with gender.” [1] In this case, pop-idol Mima, with her innocent and playful disposition, complicates the shōjo image through her ghostly existence and her haunting and threatening of Mima.

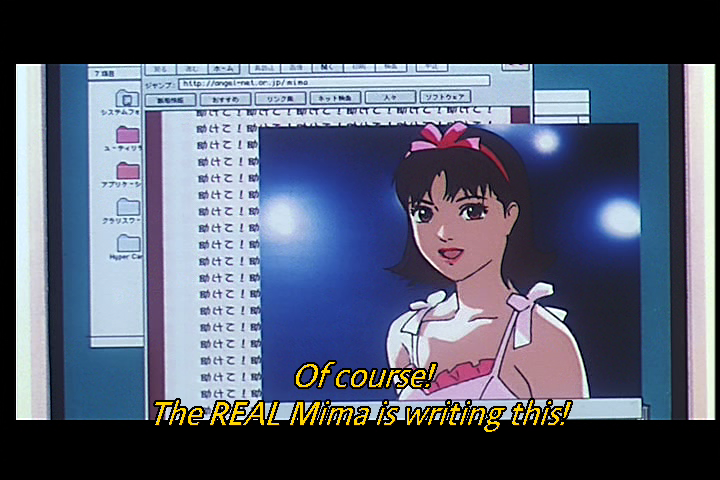

As Meg Rickards astutely notes, Mima starts seeing her pop-idol self reflected in surfaces and screens [2], and in one seminal segment, Mima checks the website and meets her past pop-idol version of herself within the computer. Pop-idol Mima seemingly converses with Mima, scorning her for having done a rape scene for a television series and calls her “filthy” and “tarnished.” No longer confined to being Mima’s reflections upon a train window or the computer screen (when it is turned off), pop-idol Mima appears as an autonomous being with influence not just in the computer realm she (or it?) inhabits, but eventually upon Mima’s world. The film suggests that while pop-idol Mima “invades” Mima’s private space, Mima may also have transgressed into the world of the computer through her delirium. Thus Mima’s room and “Mima’s Room” may actually converge into a single, albeit mysterious, space. This convergence, however, is at odds with the Mima’s fragmented psyche and identity.

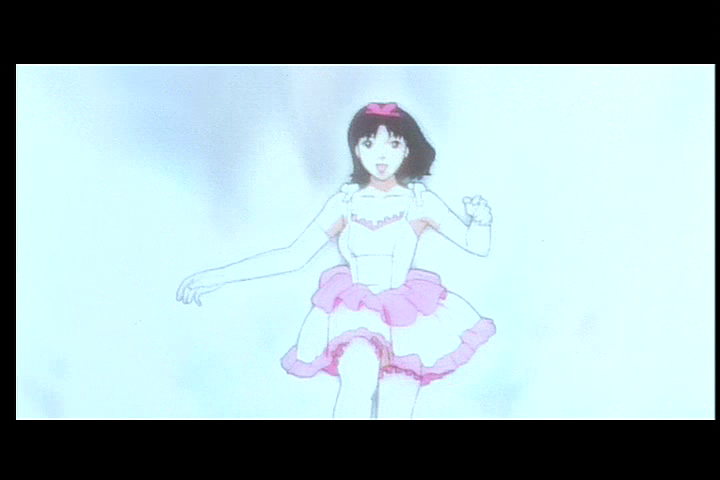

As they stare at each other, the differences between the two characters reveal the film’s warped engagement on the shōjo tradition. While the “classic shōjo,” as Susan Napier describes, may be “cute, innocent…and accommodating” [3], the shōjo can also be vulnerable and seductive [4]. Perfect Blue presents two separate entities of the shōjo image: one “innocent” and “cute” in pop-idol Mima, and the other “vulnerable” and even “seductive” in Mima herself. Whereas pop-idol Mima exudes “cuteness” and “innocence” through her perfect posture, pink outfit—a high skirt, long pink leg stockings, and a headband with a bow tie—and her cheerful laugh, the real Mima is clearly vulnerable, afraid, and even ashamed by her torrid and, what Me-mania and other characters would arguably call “seductive,” rape scene she performed on TV. As Mima sits frightened and slightly turned away in a high angle shot over pop-idol Mima’s shoulder, she appears dwarfed in comparison to the pop-idol’s stature. Furthermore, the pop-idol’s skin literally shines brighter than Mima’s, not only because the pop-idol is “a ghost of [Mima’s] former self” [5], but also because she is seemingly “innocent” and pure. Ironically, while the film presents Mima’s room and “Mima’s Room” as convergent spaces, the film refuses to consolidate all the aspects of the shōjo, instead fragmenting it into two characters that are themselves pieces of Mima’s identity.

Pop-idol Mima’s shōjo qualities of innocence and cuteness may also endow her with the ability to float, as she demonstrates by skipping across vast lengths of space. The “floating” tendency is central for female animè characters in Hayao Miyazaki’s films, as Thomas Lamarre explains. According to Lamarre, Miyazaki’s women have a deep connection to nature that allows for “a certain potential for buoyancy in relation to natural forces, to the wind” [6]. For Lamarre, Miyazaki’s women connote tenderness and innocence that allows them to seemingly float in space. Pop-idol Mima, however, subverts this tendency by the fact that she comes from a computer realm. She first demonstrates her ability to float as she skips backward across the room from the bed to the window curtains. As she does so, she smiles and even chuckles, clearly expressing her idyllic pop-idol and shōjo qualities. As she approaches the curtains, however, the film begins to further complicate pop-idol Mima’s relationship within the space of Mima’s room.

Window Scene: Pop-idol Mima, with no reflection, standing in front of what may or may not be a windowpane; pop-idol Mima standing on a ledge, clearly seen through what appears to be an open entry way; Mima runs into the windowpane and stares at her own reflection

When a shocked, frenzied Mima demandingly asks “Who in the world are you!?,” the film cuts to the pop-idol chuckling in front of the curtains, which mysteriously part. At this point, the film highlights the consequences of the convergence: just as pop-idol Mima and Mima are now in a shared “Mima’s room,” the boundary between privacy and publicity is no longer stable. Mima’s private life is on full display as symbolized by the opening of the curtains, from which anyone standing outside can see into her private space. Moreover, the breaking of the division between privacy and publicity is even enhanced by how the division between the balcony and the room is further complicated. As the film cuts to a long frontal shot of the pop-idol standing on top of the balcony ledge (smiling modestly and waving one hand, again maintaining her cheerful, “innocent” disposition), the barrier does not appear to have any drawn reflections (middle image). In fact, the film seems to illustrate the division as an opening, or a doorway. The film even confirms this when Mima attempts to run out to the balcony and, instead, hits the windowpane and briefly glances at her reflection (right image), emphasizing Mima as a character divided. The shot is the exact same as when pop-idol Mima opened the curtains and leapt through the window (left image), but unlike her, Mima is unable to pass through it. The film clearly depicts pop-idol Mima as a phantom who can freely pass through barriers, such as computer screens and windows. Moreover, after Mima opens the window and comes out to the ledge, the film cuts to a long shot of a panoramic background of streetlights. The background moves right to left, inducing a tracking movement as pop-idol Mima casually skips across the tops of each streetlight. Her “floating” quality is on full display, and as her movements slow down as she skips deeper into the panoramic space away from the camera, her whole figure fades into the background. Indeed, this pop-idol Mima is truly an apparition.

In fact, it is through pop-idol Mima’s ghostly qualities that Perfect Blue enters a territory of horror and subverts certain genre tendencies of shōjo in animè. As said earlier, Thomas Lamarre argues that “to play with gender, is to play with genre.” Arguably, thus, pop-idol Mima’s ostensible purity and “innocence” allow her to float and effortlessly skip across wide spaces. However, pop-idol Mima is the complete opposite of Miyazaki’s female characters that Lamarre describes. Because she seemingly comes from a computer space, her character actually has absolutely no “deep” connection to nature. Interestingly, then, pop-idol Mima somewhat complicates the “floating” characteristics of shōjo, making them no longer “cute” and whimsical, but rather ominous and frightening. As pop-idol Mima disappears in the panorama, for example, a close-up of Mima shows her with tears in her eyes, seemingly feeling ashamed, violated, and afraid. Pop-idol Mima’s abilities to float within the painted urban backgrounds and intrude upon Mima’s private space thus endow her with a terrifying, ghostly quality that subverts the tender qualities of “buoyancy” as evident in Miyazaki’s women and by larger extent the shōjo image.

Image Credits:

1. Pop-idol Mima emerging from the computer world (author’s screen grab)

2. Pop-idol Mima now talking to Mima from within the computer (author’s screen grab)

3. Window Scene (author’s screen grab)

4. Mima crying in fear and shame

- Lamarre, Thomas “From animation to anime: drawing movements and moving drawings.” Japan Forum 14.2 (2002): 351. Web. 23 Aug. 2010. [↩]

- Rickards, Meg. “Screening Interiority: Drawing on the Animated Dreams of Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue.” IM: Interactive Media E-Journal of the National Academy of Screen & Sound. Issue 2 (2006): n. pag. Web. 21 Oct. 2015. [↩]

- Napier, Susan J. ‘“Excuse Me, Who are You?’: Performance, the Gaze, and the Female in the Works of Kon Satoshi. Cinema Anime: Critical Engagements with Japanese Animation. Ed. Steven T. Brown. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 34. Print. [↩]

- Ibid., 29. [↩]

- Rickards, n. pag. [↩]

- Lamarre, 351. [↩]

Pingback: Perfect Blue – Visual criticism of the Japanese Idol Industrie

Pingback: Ep. 4: Satoshi Kon’s Dreamscape – Konbini Pop! Podcast 🎧

Pingback: Satoshi Kon (1963-2010) – An Anime Studies Retrospective - Anime and Manga Studies