Word Warrior Richard Durham: Crusading Radio Scriptwriter Sonja Williams / Howard University

Inventiveness, versatility, and social consciousness defined the talents of Richard Durham – an African American writer whose lyrical and politically outspoken radio dramas of the 1940s earned him posthumous induction into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2007.1 In addition, Durham distinguished himself as an award-winning journalist and poet who authored a pioneering black drama series on television, co-wrote boxing champion Muhammad Ali’s 1975 autobiography and served as a speechwriter/strategist for Chicago’s first African American mayor, Harold Washington.2

Born in rural Mississippi in September 1917, Richard Durham’s family migrated – like thousands of other Southern blacks – to Chicago, Illinois in 1923. As a teenager, Durham fell in love with poetry and several local and national periodicals published his poems.3 Durham also was drawn to the rather ethereal mass medium of radio, eventually becoming one of its more creative writers. This was a significant feat, given how few black Americans worked in this essentially “lily-white” industry during the 1930s and 1940s. In fact, a study conducted in 1947 by the civil rights organization known as the National Negro Congress (NNC), determined that Durham might have been the only Negro then working full-time as radio scriptwriter.4

Durham had honed his scriptwriting skills while working for the federally funded Illinois Writers’ Project (IWP). Beginning in 1939, Durham documented life in Depression-era Chicago with other IWP writers. He soon gravitated toward the IWP’s radio division where writers created scripts for weekly dramas broadcast on local Chicago stations.5 For WGN’s Great Artists series – dramas about artists featured in the Art Institute of Chicago – Durham’s February 1941 script cleverly revealed why Spanish painter Francisco Goya created his famous anti-war scenes during the early 1800s.6 Durham’s script quickly establishes a sense of urgency. A character named Armid frantically bangs on Goya’s door while the sounds of marching military troops intensify in the background. Suddenly, a gun is fired. A body falls. And briefly, readers are left in limbo. Who is Armid? How is he connected to Goya, and is he now dead?

Soldiers from French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s army, an invading force in Spain, soon arrive at Goya’s door searching for escaped prisoner Armid. Durham’s Goya calmly states that there are only a few pictures and paint in his studio. However, a soldier sees what he believes is a puddle of blood on Goya’s studio floor. Durham then pitches a curve ball, throwing in a detail that will take his script readers – and his soldier characters – by surprise. Goya tells Napoleon’s men that what they think is blood is actually poisonous red “paint.” Tasting a drop of this “paint” could kill a man, Goya declares. Goya’s deception scares the soldiers. But their captain demands that Goya draw something with the so-called red paint. Goya obliges, depicting Napoleon’s soldiers as monsters. Enraged, the captain forces Goya to put the paintbrush in his mouth, believing it will kill him. Once the soldiers leave, Goya tells an injured but alive Armid that he will fight oppression through his art – vividly rendering the horrors of war on his canvases. In subsequent Great Artists programs, Durham dramatized the lives of freedom-loving artists like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin.7

After leaving the IWP in 1942, Durham became a freelance scriptwriter for popular national radio shows like The Lone Ranger and Ma Perkins. And, Durham served as a star investigative reporter for the black-owned, advocacy-oriented Chicago Defender newspaper. Through his reporting and scriptwriting, Durham sought “to find the kernel of Negro life and plant it in the sunshine of some artistic form which will reveal its inner beauty, its depth, its realistic emotions, its humanness.”8

During the mid-1940s, Durham wrote for Democracy USA, a Chicago Defender-sponsored radio series about black Americans whose lives typified the principles of democracy and freedom.9 Durham also wrote and produced an all-black radio soap opera, likely the first of its kind, called Here Comes Tomorrow. It tackled issues that African Americans grappled with in a post-World War II, yet still racially segregated America.10

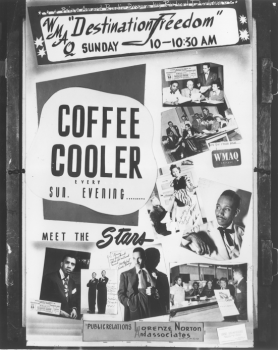

But Durham’s crowning achievement during this period was his award-winning Destination Freedom radio series. Starting in June 1948, Durham dramatized the accomplishments of notable contemporary and historical black leaders, including entertainer Lena Horne, diplomat Ralph Bunche and abolitionist Sojourner Truth. Destination Freedom’s half-hour long, weekly dramas aired on Chicago’s NBC affiliate, WMAQ – boldly advocating for freedom, justice and equality for Negroes and all oppressed people.

For example, in Durham’s script about Denmark Vesey, leader of an 1822 slave revolt in South Carolina, Vesey states, “I read the Declaration of Independence . . . it said, ‘All men are created equal.’” But given the reality of racial inequality, Vesey defiantly notes, “Until all men are free, the revolution goes on!”11 For a medium that often ignored or negatively stereotyped African Americans, Durham’s radio characters were strong, dignified, if not downright militant people.

To fuel his writing, Richard Durham sifted through mounds of documents in the Negro history collection housed in Chicago’s Hall Branch Library. Durham then skillfully crafted his dramas, alternating between relatively straightforward narratives with more whimsical takes. In the “Rime of the Ancient Dodger,” for instance, Durham paid homage to Jackie Robinson. Robinson integrated baseball’s all-white major leagues when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers team in 1947. Durham’s friend and fellow writer Louis “Studs” Terkel played Sammy the Whammy, the show’s narrator. Durham used rhyme, humor and fantasy to let Sammy witness and comment on the discrimination levied against Robinson as soon as he stepped up to the batter’s plate:

Sammy:

There wuz umpires, umpires everywhere,

an’ the pitcher hadn’t thrown a ball.

But when this Robinson ups to the plate

Some ghostly umpire calls. . .

“S-t-r-i-k-e a t-[w]-o-o”. . .

Here wuz an’ umpire callin’ two strikes on a man

before he gets to bat,

an’ the bleachers wuz quiet like that.”12

Studs Terkel raved about Durham’s “talent for capturing the idiom, not just the African American, [but] the American idiom. He was just gifted.”13 When Durham’s Destination Freedom series ended its run in August 1950, he continued writing and influencing people through Chicago’s labor union movement, and through his editing of the Nation of Islam’s weekly national newspaper. Until his death in 1984, Durham remained a crusading writer and activist – a word warrior extraordinaire.

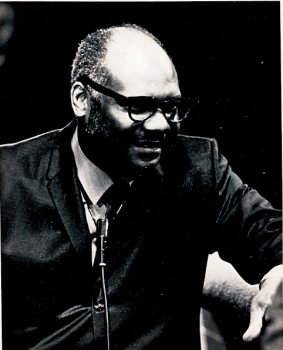

Image Credits:

1. Richard Durham, Courtesy of Clarice Durham.

2. Club DeLisa, Courtesy of Clarice Durham.

3. Destination Freedom, Courtesy of the Richard Durham Papers, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public Library.

- National Radio Hall of Fame: Richard Durham, accessed May 1, 2015, http://www.radiohof.org/richard_durham.htm [↩]

- “Bird of the Iron Feather,” accessed May 5, 2015, http://www.wbez.org/blogs/lee-bey/2013-02/bird-iron-feather-look-back-tvs-first-black-soap-opera-produced-chicago-105475; Muhammad Ali with Richard Durham. The Greatest: My Own Story, Random House, 1975; Renault Robinson interview with author, March 12, 2010. [↩]

- Richard Durham, Richard Durham Papers, Chicago Public Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, box 6, folder 12. (hereinafter Durham Papers) [↩]

- “The Negro’s Status in Radio,” 1947, Papers of the National Negro Congress, part 1: Records and Correspondence, reel 34, series 2, NNC Records of the Executive Secretaries, 1943–1947, Harsh Research Collection, box 69, folder 0216, 1–2. [↩]

- Jerre Mangione, Dream and the Deal: The Federal Writers Project, Little, Brown, 1972, 128. [↩]

- Richard Durham, “Goya: The Disasters of War,” Great Artists, February 11, 1941, Durham Papers, box 5, folder 3. [↩]

- Federal Writers’ Project, “Works Progress Administration, Special Studies and Projects, Regional and National Files,” Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, boxes A862-A867, folders—Radio Scripts, Illinois. [↩]

- Hugh Cordier, “A History and Analysis of Destination Freedom,” 1949, Durham Papers, box 6, folder 4, 24. [↩]

- Richard Durham interview with J. Fred MacDonald, 1975. [↩]

- Richard Durham, Here Comes Tomorrow, September 1947, scripts, Clarice Durham personal files. [↩]

- J. Fred MacDonald, Richard Durham’s Destination Freedom, Praeger, 1989, 70, 62. [↩]

- Ibid, 234. [↩]

- Louis “Studs” Terkel, interview with author, May 30, 2001. [↩]

Refreshing and inspiring to learn more about this multi-talented artist-activist who used his skills to tell stories that would not, in those days, be heard anywhere else! The flyer advertising the weekly social captures the imagination: what must those conversations have been and how they must have nourished the conversants… It’s also an idea worth adapting to 21st century social media. Prof. Williams eagerly awaited biography of Richard Durham is full of gems like this one.