Media and the Movement: Activist Community Radio in the American South Joshua Clark Davis / University of Baltimore Seth Kotch / University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

When WAFR-FM, a three-thousand watt radio station, went on the air on the morning of September 15, 1971, few residents of Durham, North Carolina expected much from the upstart broadcaster, if they were even aware of its existence. The founders of the station, according to a local newspaper, hoped to “involve community leaders, professional people, ministers, and housewives in discussion of issues of interest to blacks.”1 As Ralph Williams, a community activist and station cofounder explained, “we don’t feel that advertising should be the major work of a radio station.” Otherwise the station’s founders gave few hints as to their broadcasting intentions.

Indeed, it was only with their first musical selection, that WAFR’s staffers revealed how unconventional, and even radical, their programming would be. After a voice quickly announced the start of broadcasting, WAFR played the first two albums of the New York spoken-word group, the Last Poets, uncensored and in their entirety, including songs like “When the Revolution Comes” and “White Man’s Got a God Complex.” Although the Last Poets’ eponymous 1970 debut album had emerged as a surprise hit and sold over 300,000 copies, FCC guidelines had prevented other radio stations from playing the bulk of the group’s work, which featured no shortage of profanities. The Last Poets stridently and unapologetically embraced Black Power and enjoyed personal ties with leading black nationalists, including Amiri Baraka and the Black Panthers. As Donald Baker, one of the original staffers of WAFR, remembered, playing the group on the station’s inaugural broadcast “was radical—and probably the best reflection of the intent of the radio station.”

That day in September 1971, WAFR became the first ever black-controlled, non-commercial community broadcaster in the United States. Not only that, but WAFR appears to have been the first ever black nationalist broadcaster in the country, with an all-black staff that celebrated Black Power over the airwaves with recordings of Malcolm X, black history programs hosted by a local professor, and even an independently produced, African American alternative to Sesame Street, the Children’s Radio Workshop. WAFR even made pan-Africanism a part of its call letters, which stood for “Wave Africa.” The station fused the tradition of radical community programming pioneered by Pacifica with the relatively new format of African American noncommercial radio, which had its origins in the founding of WHOV at the historically black Hampton University in 1964. Although WAFR would close after five years due to financial and personnel difficulties, at its height it reached roughly 75,000 listeners in the North Carolina Piedmont area with a blend of black radical politics, community programming, jazz, and soul music.

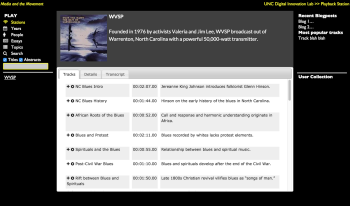

Until recently, the sparse scholarship done on community radio in the United States has passed over the American South. In response, Media and the Movement is documenting the rich history of southern community radio with an extensive series of oral histories and digitization efforts funded by two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, its Collaborative Research Grant and a Digital Projects for the Public Grant. In addition to WAFR, we are focusing on two other radical community radio stations founded by Southern civil rights and antiwar activists—WRFG in Atlanta and WVSP in tiny Warrenton, North Carolina—as part of a larger project on activist media throughout the region in the 1960s and ‘70s.

As we conducted our oral history research, we encountered caches of audio recordings in attics and garages. These reels, many of which were donated from other stations and overdubbed by station engineers, are decades old and profoundly endangered, damaged by mold and less-than-ideal storage conditions. Using George Blood, LP, we have cleaned and digitized 160 reels containing recordings of call-in shows, musical performances, opinion pieces, reporting, community events, and more, not to mention WAFR’s Children’s Radio Workshop, one episode of which features an eerily prescient skit about Chicken Little, reimagined as an African American boy who is struck by a police officer. Other recordings include live speeches by nationally prominent activists traveling through the South, including Bobby Seale and California socialist Congressman Ron Dellums, and an out-of-print, fifty-episode “people’s history” of Atlanta audio documentary series produced by WRFG. We are currently at work creating tape logs of all this audio, which is being stored in the UNC Libraries. We have also begun a planning for a permanent, physical donation so the reels will be preserved in perpetuity.

And we have begun work on this project that will address a core problem in oral history and no doubt in media studies, too: no one is listening. Oral historians were among the first to adopt digital tools for academic production, and since those early days have benefited substantially from the widespread digitization of oral histories in large-scale collections. Yet few people listen to oral histories and oral historians are at least partly to blame. In their eagerness to digitize their output, they failed to consider that the digitization of text transcripts would provide a persuasive disincentive to listening; it’s just easier to read. Thus the onus has fallen on archivists and their allies to create digital environments that encourage listening. When my colleague and I came across a trove of historic radio recordings, we set out to do so.

This year we started work in the University of North Carolina Digital Innovation Lab to begin development of Playback Station, a browser-based, open-source, open-access media curation platform designed to present historic and contemporary media material and interpretation thereof to a wide public. Its development is based on two key principles:

1. When dealing with aural sources, listening is essential.

2. Users desire a flexible, familiar interface that will bring researchers what they need and browsers serendipitous encounters.

Its design rests on the organizing concept of the album—a collection of tracks gathered under a heading. Each sound recording is given a title (“Oral History with Jane Doe” or “Children’s Radio Workshop”) and is segmented into a number of tracks, each of which is labeled with its own title and descriptive tags. Users will be able to search and browse for albums and tracks and create playlists using functionality from SoundCloud as they move through the collection. A user might elect to listen to part of a lecture on Black Power delivered on the Duke University campus in the 1970s, then to a live in-studio performance by a North Carolina blues musician, then an oral history with the deejay who was on air that day. The text of these recordings will scroll as the user listens, and that text will be interactive: clicking on a word or phrase in a text will prompt the audio to play from that point. In this way, listeners can scan audio with the same efficiency with which they scan text. Each oral history and radio segment will be paired with descriptive and interpretive content which will maintain context and inform users as they listen.

Playback Station will use text records, then, as nudges to listen rather than as substitutes for it. And we hope it will empower members of our community to become listener-deejays, curating their own aural experiences and calling back to the spontaneity and vitality of the live radio of the 1970s. When it is complete, we hope Playback Station will not only immerse listeners in the richness of these radio programs, but also demonstrate the unique blend of music, community-created content, opinion pieces, and organizing that made them remarkable.

PS. Media and the Movement is collecting materials from three radio stations, but only one of those stations–WRFG in Atlanta–is still broadcasting today. However, WRFG is currently in danger of going off the air if it can’t repay $40,000 in back rent for its tower. If you’d like to support one of the most important independent community broadcasters in the country, please consider making a tax-deductible donation at http://www.wrfg.org, where you can also listen to the WRFG’s rich and varied musical and political programming online.

Image Sources:

1. Obataiye Akinwole, Ebony, June 1973, p. 116.

2. WAFR Logo, courtesy of Davis, scanned from WRFG F89.3 FM Program Guide, July 1981.

3. Children’s Workshops

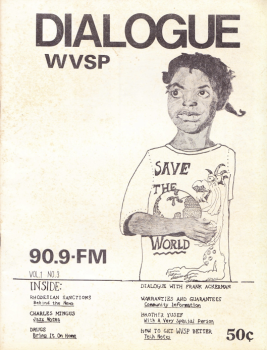

4. Dialogue Cover

5. Staff of WSVP

- “Noncommercial Station Set to Train Black Broadcasters,” Durham Morning-Herald, September 14, 1971. [↩]