The Future of Television is…Comics?

Alisa Perren / University of Texas at Austin

One of the most anticipated shows of the fall 2013 season was Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Marvel’s skillful and profitable expansion of its cinematic universe from Iron Man through The Avengers, along with Joss Whedon’s widely reported involvement with the launch of the series, led to tremendous enthusiasm on the part of critics, journalists, and fans about the new series. Speculation ran rampant: Would Marvel do for television what it previously had done for movies? Might this mark a new moment in the movement of comic book properties to television? How might the company expand the storyworld and characters through a big-budget, high-profile weekly broadcast series supported by all the resources at parent company Disney-ABC’s disposal?

Unfortunately, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. did not live up to the pre-broadcast hype. In spite of extensive promotion, the show’s viewership rapidly declined. Many viewers (myself included) found the show’s cardboard characters and superhero-adjacent storylines uninteresting and unworthy of weekly viewing. Marvel’s investment in maintaining the economic value of its cinematic superhero universe diminished the economic potential for its first major live-action television venture. The very financial success that the company had with its motion pictures demanded that it reinforce a distinctive cultural hierarchy – one in which the characters (and performers), action, and special effects of its motion pictures eclipsed those of its first television series. Industrial valuation translated into cultural valuation in a very explicit manner, at least in the case of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.

Given the current industrial and creative landscape, in which journalists, critics, and talent regularly claim that “television is the new cinema” and “TV is better than movies,” this reinforcement of cultural and creative distinctions between film and television through Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. is particularly striking. Entertainment companies, it seems, have not yet fully figured out the formula for transferring comic books – especially superhero properties,1 my primary focus here – to television. This is not to say that there haven’t been consistent efforts over the years. From The Adventures of Superman (1952-1958) to Batman (1966-1968), Wonder Woman (1975-1979) to The Flash (1990-1991), Lois & Clark (1993-1997) to Smallville (2001-2011), there have been steady, albeit limited, attempts to translate comic book properties to live-action TV.2 Each decade has been marked by a few such ventures, but none has proven to be a megahit in the way that so many superhero movies have been for decades.

Indeed, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., though still on the air, is unlikely to represent the “future” of comics on television, let alone the future of (successful) corporate synergy or transmedia storytelling. Yet looking into my crystal ball, I would venture to say that the time is coming for superheroes on television – not to mention for a more expansive new phase in the comics-television relationship. As often has been noted, comic book properties have piqued the Hollywood film industry’s interest in recent years because they appeal the elusive yet desirable young male viewer and because they are viable sites for transmedia marketing, storytelling, and fandom. As Andy Greenwald observes, big-budget superhero films in effect have become serialized television – except that new installments of “episodes” of The Avengers appear in theaters once or twice a year and are discursively produced as distinctive from television in the interest of product differentiation and theatrical attendance.

Thus far, producers of live-action TV series have found it far more challenging to adapt comic book-based properties than have motion picture producers. Two programs, however, currently suggest the potential and possibilities for comics on TV: The Walking Dead (2010- ) and Arrow (2012- ). Much ink has already been dedicated to the blockbuster success of AMC’s The Walking Dead, so I will simply note here that this program suggests the potential for using non-superhero comics as a jumping off point for serialized storytelling and characterization.

Arrow is a different story. This show’s trajectory, even more so than The Walking Dead, suggests that the industrial and creative imperatives of the comics and television industries are intersecting to a greater degree than ever before. The serialization so common in comic books dating back to the 1960s has become the norm in prime-time television, and Arrow has been able to effectively meld the storytelling strategies developed in both media forms over the last several decades. Significantly, writers for the show, including writer-producers Marc Guggenheim and Andrew Kreisberg, also have written extensively for comics, indicating the cross-fertilization of creative labor at work here.

The show expands on the well-established WB/CW formula forged with shows ranging from Dawson’s Creek (for which Arrow writer-producer Greg Berlanti wrote) to Veronica Mars while improving upon the worldbuilding and characterization initiated with Smallville. Though initially Arrow relied heavily on “cases of the week” and owed more than a little to Nolan’s Batman franchise (not to mention Lost and Robin Hood) in style, structure, and tone, as the show has developed over the last year-and-a-half, the characters have become more well-rounded and the storyworld has expanded more organically. What’s more, the action scenes have come to rival those of many motion pictures.

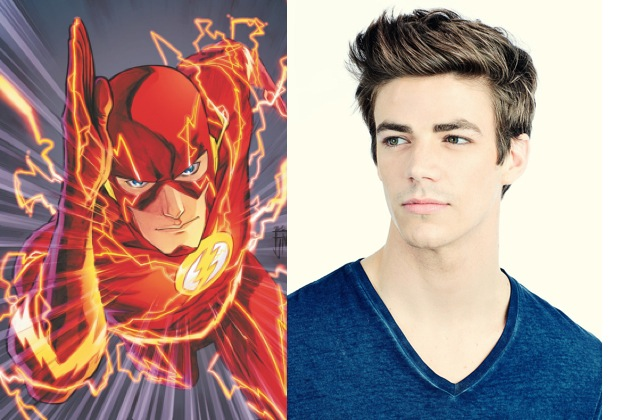

The recent introduction of Grant Gustin as Barry Allen (soon to be The Flash) as set up for a new CW series for 2014 – as well as the introduction of Arrow to Netflix streaming – suggests that the awareness of the show, its storyworld, and its characters will continue to grow.3 Current media chatter suggests that, whereas Marvel has sought to maintain a clear division between its “film” and “television” characters thus far, DC Entertainment might just be developing characters (and performers) who will transition much more seamlessly from small screen to big screen and back again. It remains to be seen how – or if –this might contribute to a revaluation of each medium both industrially and culturally.

Although Arrow offers one direction that comics-TV convergence might take, several other projects offer indications of what is to come, including:

• The creation of a TV division at comics publisher IDW;

• Development of the Garth Ennis/Steve Dillon comic Preacher (Vertigo/DC Comics) at AMC;

• Development of comics iZombie (Vertigo/DC Comics) and Hourman (DC Comics) at The CW;

• Development of DC Comics’ Gotham at Fox;

• Development of DC Comics’ Constantine at NBC;

• And of course, the much-reported Marvel-Netflix multi-series deal.

While these projects are certainly interesting from the perspective of transmedia storytelling and corporate synergy, it is worth underscoring that there are many other components to the comics-TV relationship that remain to be examined in greater depth. From a media industry studies perspective, what I find especially intriguing is the extent to which the creative practices, management strategies, production cultures, and corporate structures of the comics and television industries are impacting the shapes the stories take and the ways that characters are developed for each medium. As new platforms (and new TV series buyers) continue to emerge and the means of consuming television expand still more, the television and comics industries have the potential to become even more co-dependent. As the brief discussion of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and Arrow above suggests, comics provide a fascinating site through which to think through industrial transformations and cultural valuations in convergent-era television.

Image Credits:

1. Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. cast

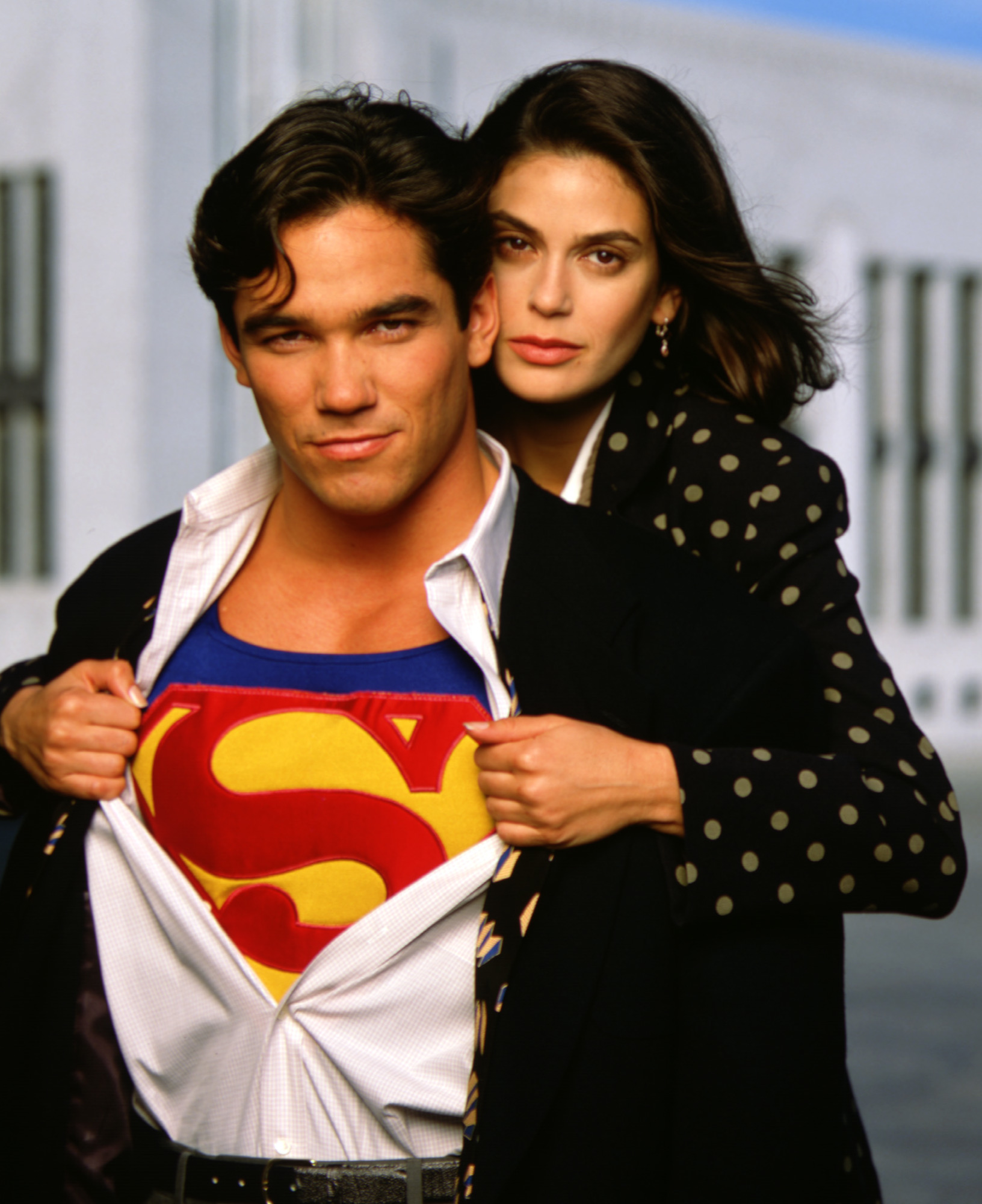

2. Lois & Clark

3. Arrow season 2 cast

4. Grant Gustin as The Flash

Please feel free to comment.

- Space constraints lead me to conflate the superhero genre of comics with the medium more generally. There is a wide range of non-superhero based comics. [↩]

- Shows such as M.A.N.T.I.S. (1994-1995) and Heroes (2006-2010) represent unofficial interpretations of comic book properties. [↩]

- The character of John Diggle (introduced in the TV series Arrow) has since been incorporated into the comic book series. This is just one of many examples of how comic book characters and storytelling strategies are not just informing TV series, but TV series are also fueling comics stories (e.g., Vampire Diaries, Buffy the Vampire Slayer comic books). [↩]

Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. has gotten slightly better in terms of characterization, seemingly in response to audience criticisms, but I am much more interested in the tone and storytelling that will take place in the new Marvel/Netflix series. S.H.I.E.L.D. is under so many constraints creatively, such as trying to be family friendly and copyright issues with the X-Men that renders them unable to mention mutations or certain superpowers. Hopefully the Netflix deal will allow for more freedom and originality.

Comic books will continue to be not only movies and video games, but also television shows. But comics were not only adapted into live-action television shows, but also into cartoons. The article only talks about live-action shows based on comic books, but I feel that cartoons should have also been examined since some of the most popular cartoons were based off of comic books too such as Batman: The Animated Series from DC Comics and Spider-Man: The Animated Series from Marvel Comics.

Agents of S.HI.E.L.D started out rough, but it is constantly getting better and better as the show progresses. The storylines and the writing have improved. I was very excited when the show was announced and had high expectations. After the first week I hoped that it would get better as my expectations were not quite met. I thought it was good but it could have been better. I felt the same way when Arrow first came out as well. Another thing the audience does is comparing the CW’s Arrow to ABC’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. These shows are two entirely different shows and cannot be equally compared.

This topic is appeal to me particularly because of its perspective on the relationship between films, comics and TV. It is always questioned that if the spectatorship in film is equal to TV, which leads to some different strategies of narrative, marketing and promoting methods in TV and films. For me, it is quite interesting because of the “migration” of the audiences.

On one hand, the linkage of comic-film-TV has settled a fundamental group of fans. Fans follow the characters despite of the media form, and migrate from one media to another. Basically, they are different from casual viewers of TV, films or comic, they are the followers of the genre and subject themselves. Many of Henry Jenkins’s theories can be utilized in this case, that fans are an unique and active group of audiences who participate in their own communities. In S.H.I.E.L.D, a big problem from my point of view is that the characters are not superheros, and they don’t have much fans. Admittedly, agents are popular, but they have never became those super characters in any of Marvel’s films. They don’t share the same fans group as the superheros. A strong evident to this is that in S.H.I.E.L.D, the episode linked to Thor2 caught a incredible hit in audience rating. Hence in my opinion, comic based TV still has a group of loyal fans. Along with the establishment of the whole comic world of comics and films (which Marvel and DC are devoting themselves to do), TV will join this new kind of industry.

On the other hand however, as Prof. Perren points out in her article, that industrial valuation has transformed into cultural valuation because of the differences among media forms. To a certain extent, TV drama series require less actions and special effect than movies. However, in order to accomplish a financial circle around comic, TV and films, companies like Marvel has no choice but to input more into TV series. Their present strategy seems like an embarrassing effort to make their TV series look like films as much as possible, to “reinforce a distinctive cultural hierarchy” according to Prof. Perren. That probably is because that S.H.I.E.L.D is later than Avengers, the most successful superhero movie ever. They assumed that their audiences (or rather fans) are expecting an “expensive” drama because they accepted the film first. Situations are different to The Walking Dead and Arrow since their audiences are migrating from comic books and their references are still around a 2D visual point. In other word, TV as a form of mass media, is quite medium between comics and films. Therefore the industrial strategy for those comic based drama series should be considered in a more comprehensive way. I am totally agree with the article that the time for superheroes TV drama is coming, although from an industrial perspective, there is still a quite long way to go.

Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. ratings have managed to stabilize. Currently, the superhero television series is only second to NCIS with 6.5 million viewers between the ages of 18-49 and ratings between 2.1 and 2.2 (compared to a 1.2 rating on October 29, 2013 ). However, its short and rocky trajectory on television suggests that, although comics have shown to have a place in television, perhaps the future of “megahit” television resides in old works of literature, which appeal to a wide demographic that extends beyond the “young male viewer.”

Thus, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.’s disappointing decline of viewership for its first few episodes cannot be solely attributed to the poorly developed characters or “Marvel’s investment in maintaining the economic value of its cinematic superhero” but to an exceptionally competitive television universe that increasingly features folk stories and fairytales. Ultimately, when it comes to television, audiences have shown to gravitate towards series based on popular literature (e.g. works from the Brother’s Grimm, Washington Irving, etc).

Television series such as Sleepy Hollow, Sherlock, Once Upon a Time, Dracula and Grimm (in its third season with decent ratings and previous nominations for a People Choice Award and Primetime Emmy, among others ) illustrate the manner in which television networks benefit from extracting beloved popular literary works in public domain and will continue to do so in the future (e.g. ABC is said to be working on a series that will include a modern-day Frankenstein) with potential for mega success.

So, although Alisa Perrin predicts the “time is coming for superheroes on television,” it is possible that as long as works of literature (in public domain) are converted into television series, comics superheroes on television (even those with flamboyant motion picture quality “action, and special effects”) will take a back seat to vampires, monsters and princesses.

The article brings to the fore an important aspect of why we as audiences are drawn to television or to cinema in the first place? Television and Cinema have existed side by side, amicably, for a long time now. However, with the growth of technology and social media diminishes the differences between the respective mediums — particularly in terms of quality and expectation. The merger of cinematic quality and engaging content is the new mantra for TV, something people have started categorizing as cine television. Times are changing and quickly so. Growth of social media like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter gives you no room for slack. If you don’t produce a quality show or product, thousands of reviews are written within minutes. The phrase “second chance” is fast diminishing; particularly with the worldwide audiences becoming more aware, educated and proactive. Yes, education is an important factor that determines how an audience perceives content on television. Viewers today have dozens of options to choose from — there are YouTube channels, television channels, films, interactive gaming and so forth. The audiences’ thirst for higher quality is soaring. So if the content producers are not on top of it, be it film or television, chances are that the show will fade away and never make it big. The visual world is an ocean brimming with innumerable possibilities and outcomes. So if the content is not engaging and refreshing, chances are it’ll sink to the bottom and never resurface.

Superhero films are larger than life. They’re glossy, high-octane roller coaster rides that take the audience on an emotional journey. It helps you reconnect with your childhood hero(most of us have one) and also helps bring back memories of having grabbed say that first comic book ever. So young or old, superhero films have always fascinated audiences worldwide. One can’t help but admit that when you see say like a Spiderman or Superman, getting all heroic and brave on the big screen, with dollops of high adrenaline action to go with it — it’s sheer magic; the power of cinema. The big screen has a charm and magic of it’s own that television will never be able to recreate. Sometimes it’s not about content as much as it is about the experience. Superhero films are meant to be watched with a big bucket of butter popcorn, along with your buddies on a big movie screen. The very experience of seeing your favorite superhero unleashing his array powers and saving the world on a 70mm screen is hard to recreate at home with a television set; even though you may have your buddies and a bucket of popcorn to go with it.

The point I’m trying to make is that, Television has its own charm and beauty; so does Film. Over the years we have witnessed television uplifting itself and becoming more high quality — both content and production wise, however, it still leaves much to be desired in terms of creating a complete movie goers experience – the juice, the thrill, the excitement is not quite as high. That’s where film scores over television. It injects you with enough excitement, emotion and story in a two-hour package. And sometimes, a short effective dose of extreme entertainment is what one needs. Therefore, superhero movies are received better on the big screen than say on a television set. It’s more for the experience of watching Spiderman fly over skyscrapers and beating up Green Goblin on the big screen with say 500 other people in one big auditorium! The cheering, the anticipation, the popcorn, standing eagerly in the ticketing line and definitely the round of applause that follows at the end of a well-constructed film. Therefore, although television shows based comic heroes may do well, considering the bright future of television, it can never be the same as watching it on a big screen. I’d say it’s like watching the Iron Maiden performing live or listening to the at home on a record. I’d watch them perform live, any day. Superheroes are fictional characters, nonetheless, watching them on a 70mm screen is the closest you’ll get to the “live” experience.

Therefore it’ll be hard for me to comment on whether the future of television is comics. I think both television and film have one thing in common. They serve as a medium for sharing stories with their audiences. What’s story about? Emotion. How does one feel emotion? When you connect with the characters. Can you connect with characters on the small screen, like when watching something on a TV set? Yes indeed. But what are superheroes all about? Story? Yes. Emotion? Yes. Action? Yes. Best way to experience explosive action? A TV set? Maybe not. The maybe on a big screen with 500 other people and superior quality sound? Yes sir! The point I’m trying to make is that certain genres of film like superhero films deserve a big screen viewing experience and a smart audience will always want that? So when given a choice between experience and convenience, most comic hero fans would opt for experience, I’m sure.

While superhero comic book franchises have appeared with increasing frequency on American screens, big and small, their recent popularity on television seems to me a continuation of an established industrial effort to appeal to young readymade fan communities of science fiction and fantasy franchises. Although Syfy has recently branded itself as the home for tongue-in-cheek science fiction schlock movies a la Sharknado, the Sci-Fi Channel of yesteryear worked with Hallmark Entertainment to release high production value miniseries adaptations of popular science fiction and fantasy franchises like Children of Dune (2003) and Earthsea (2004). Before that, Hallmark paired with the Disney Channel in 2002 to adapt the fantasy book series Dinotopia (2002), spending roughly $80 million on the miniseries but casting few recognizable actors. Banking on the franchise appeal of the books and visibly high production values instead (the miniseries received an Emmy for visual effects in 2002), Dinotopia seems to have presaged the current successes of Game of Thrones. And, as a rare exception to the history of lackluster live-action superhero shows you’ve described (although I agree with Pierce that animated superhero series are important for this discussion), I would note the popular series The Incredible Hulk (CBS, 1978-1982). What interests me most about the trend you’ve identified is the increasing convergence between film and television projects, with television series and film franchises designed to interact within a shared narrative universe.

Although Marvel appears to have beaten other franchises to this punch, I also see this trend within the context of previous television adaptations of science fiction and fantasy franchises. In the wake of Disney’s 2012 acquisition of Lucasfilm, Disney-produced Star Wars television series are already underway, but Lucasfilm also worked with Cartoon Network between the releases of the second and third prequel films in the early 2000s to produce the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2003-2005), which would then be rebooted as a computer-animated series in 2008. Just as Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. explores and expands a marginal aspect of the Marvel film franchise, both iterations of Star Wars: The Clone Wars explored and expanded the events that took place between the second Star Wars prequel film Attack of the Clones (2002) and the third prequel film Revenge of the Sith (2005), bridging the gap between the two theatrical releases. In addition, in 2010, NBC Universal developed an adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower novels that would blend film releases with a regular television series, although the series would never materialize (Time Warner has subsequently toyed with the same idea).

I wonder, too, whether the reboot culture of contemporary American comic book adaptations will have a significant impact on the increased convergence between television and cinema (or, conversely, whether the increased convergence between television and cinema will dampen reboots). Given Kevin Feige’s recent claim that Marvel Studios has planned its studio releases through 2028, the latter seems more likely, although Batman’s new appearance in the upcoming film Batman vs. Superman (2016) suggests that reboots may be around to stay. The apparent willingness of audiences to accept frequent re-imaginings of established franchise characters suggests that transmedia franchises can allow television adaptations to differ from and even contradict related theatrical releases, but also that source comics are less important to general audiences than they may be to devoted fans and content creators. I was particularly intrigued by your consideration of whether or not the upcoming spate of super-hero television shows will take advantage of the serial narrative strategies of comic books. Given the blend of episodic and serial narratives that have variously structured comic books and graphic novels, I agree that it would be exciting and refreshing to see new narrative forms emerge in popular television.

Pingback: Stasis, Change, and Televisual Comic Book Film Franchising Derek Johnson / University of Wisconsin-Madison | Flow

Pingback: What Impact Does the CW’s Stargirl Show Have on Network TV? - bznewz