Flow Favorites: Seeing in Spanish: The Nat King Cole Show

Herman Gray / University of California in Santa Cruz

Every few years, Flow’s editors select our favorite columns from the last few volumes. We’ve added special introductions and included the original comments to the piece below. Enjoy!

Flow Co-Coordinating Editor Keara Goin:

Herman Gray in this piece addresses the complexities of African diasporic connections that have a musical alignment and confluence. Linking the work of musician David Murray to that of Nat King Cole, Gray articulates a sonic thread running through the web of the Black Atlantic. The Spanish language recordings of Latin American music by both African American artists, what Gray terms diasporic conversations, inspire him to reflect on the power of transnational musical expression to provide people with a way to hear visually and see sonically. Concluding with a reflection on contemporary African American-targeted media, Gray laments the relative inability for diasporic projects like Cole’s or Murray’s to be utilized in these media spaces.

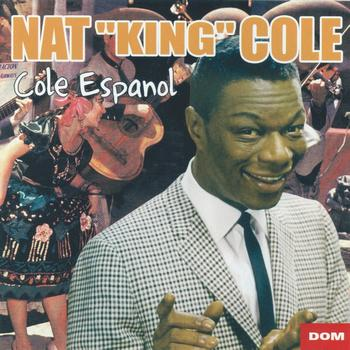

Long before he was a television host and celebrity Nat King Cole was an accomplished jazz pianist and song stylist. Over the course of a very successful musical career Cole recorded hundreds of songs with his innovative jazz trio including a series of records featuring classic song from Latin America including pre-Castro Cuba.

In his most recent compact disk release, David Murray’s Cuban Ensemble Plays Nat King Cole (En Español) (3d Family 2011; 3d Family.org), saxophonist, composer, and arranger David Murray revisits some of these classical Latin American recordings by Cole. David Murray’s reinterpretation of Nat King Cole prompts me to rehear The Nat King Cole Show, especially in the context of black televisual presence in today’s digital platforms. What Murray has done with this remarkable project is to signal some of the radical possibilities in sight and sound, hemispheric transnationalism, border crossing, and the politics of representation that Nat King Cole gestured toward in the short run of his television show. David Murray’s sonic riff on Cole’s often commercial and sometime brazen south of the border collaborations is no mere project of nostalgic recuperation either. David Murray links Nat King Cole’s sonic presence on television to a powerful musical tradition and diasporic conversation.

Murray’s exploration of Cole’s Latin music archive provides the chance to reflect on Cole’s impact on 1950s American television sonically (through Murray’s sound, arrangements, and reconnections to what Jelly Roll Morton called the Spanish tinge) rather than just visually. Indeed for me Murray’s recording suggests a conception of Cole as Ellingtonian, a figure exuding the celebrity persona necessary to command a television show and cultural gravitas to disturb (even if momentarily) the racial order of things. Murray, who came of age politically and culturally in the 1960s, uses the musical and television legacy of Cole to take listeners through the history of exchange, collaboration and borrowing from Cuba, Mexico, Argentina, and Puerto Rico; Murray places Nat King Cole in the company of black American composers and performers (e.g. Randy Weston, Sarah Vaughan, Josephine Baker, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, John Birks Gillespie, Miles Davis, Melba Liston, and Sonny Rollins) who musically probed black American diasporic connections to Central and Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

Forging connections to the political and racial history of the US and Latin America in the 1940s and 1950s is fraught since it is saturated as much by nostalgia for the good old days of resorts and playgrounds for the wealthy as by illicit commerce, Jim Crow racial terror, economic inequality, and authoritarian governments. Yet, it is precisely these collaborations, both Nat King Cole’s original work with musicians in Cuba, and Mexico and David Murray’s contemporary collaborations with musicians in Cuba, Argentina, Spain and Portugal, that continue the complex sonic transactions that go back to the founding moment of black Atlantic exchange and exceed the boundaries of the national and the visual.

Sonically, Murray manages to do what television could not or perhaps, more to the point, would not. That is, make explicit Nat King Cole’s (and black America’s) cultural and aesthetic alliances with diasporic communities of affiliation in Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. After listening live and on record to David Murray’s Cuban Ensemble play the Spanish music of Nat King Cole when I see black and white television footage of Nat King Cole on fifties American television it is not just though the patina of nostalgia for the golden age of television or the liberal American gesture toward racial tolerance. (Anna McCarthy’s excellent, The Citizen Machine: Governing By Television in 1950s America analyzes, in rich and fascinating detail, the role of American broadcast television in the story of liberal racial tolerance.)

This is a double move too. Cole’s musical collaborations with musicians in pre-Castro Cuba occurs at the same time as black artists like Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, and Paul Robson in the US and revolutionaries like Fidel Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara in Cuba were helping to imagine and usher in a new world. In his embrace of Cuba, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil, both Nat King Cole and David Murray continue to forge sonic links among black diasporic speaking communities in the global south and the global north.

What better translator to reanimate this imaginative possibility for our time than David Murray. The songs featured on David Murray’s Cuban Ensemble Plays Nat King Cole (En Español) include some of the most recognizable and frequently recorded Spanish language material—“Quizás, Quizás, Quizás,” “Cachito,” “Piel Canela,” “A Media Luz,” and “Aquí Se Habla en Amor.” Murray’s arrangements update the Nat King Cole songbook without sacrificing the soul of the music or the richness of its tradition.

To hear this material and to look at that old television footage now is to see different black Atlantic communities with distinct cultural histories engaged in diasporic collaboration and celebration. While this collaboration is neither original with Nat King Cole nor unique with Murray today (others worth noting include Steve Coleman, Jerry Gonzalez, Roy Hargrove, Stephan Harris, Regina Carter), with this recording Murray conjures something valuable and important, what I would describe as the invitation to hear visually and to see sonically in the black Atlantic sonic and visual imagination.

This raises the question thus, of what The Nat King Cole Show and the Latin American songbook might mean for black televisual presence in the US today with the new crop of new black owned, themed, and focused broadcast platforms: OWN (Oprah Winfrey Network cable network which partnered with The Discovery Channel), Bounce TV (broadcast network started by Ambassador Andrew Young and Martin Luther King III), TV One, BET (Black Entertainment Television). Ironically, like the broadcast environment in Cole’s time, these days black original programming is a rarity in the contemporary prime time schedule. Unlike television in the mid-nineteen fifties, black characters and black story lines are considerably more dispersed and visible across broadcast and cable programming schedule.

What is more, it is not surprising that more black owned cable and media platforms appear with the transformation of the digital television environment and capacity to identify and reach distinct demographic niches. For the new black focused networks, access to the archives of global entertainment companies like Viacom makes syndicated programs and reality-based appeals to race, gender, and lifestyle more cost effective than expensive original scripted programming. Russell Simmons, BET, and Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Productions demonstrated that they could brand and market blackness across different media platforms. BET and then TV One proved the financial viability of stocking the broadcast schedule with low cost and high return programming. So viewers turning to recent ventures emphasizing black themed content will find a mix of old movies, sports, syndicated situation comedies, in-studio talk shows, and canned programming from the archives of parent and affiliated companies.

What, I wonder, of the histories, collaborations, aspirations, and memories in this generation of broadcasting platforms aimed at black audiences? The programing offered by these new ventures model middle class arrival and tutor viewers in normative ideals of citizenship and self-improvement that turn histories of struggle and collective action into iconic images and heroic individual efforts. The poor, displaced, and most marginalized sectors of our communities stand as the limit of what is morally permissible and at the limit of a social order that continues to be ordered racially. David Murray’s homage to Nat King Cole’s Español recordings and The Nat King Cole Show taken together evoke, for me, the hidden histories of black diasporic collaboration and circulation. Unlike Murray, the account of our present and the programing choices presented in the new black owned platforms remind us as much about the exploitability of the black market niche for corporate investments and brands as they do about the unwillingness of sponsors a generation ago to invest in The Nat King Cole Show, because it defied the racial order.

Image Credits:

1. Nat King Cole en Español Album Cover

2. David Murray

Original comments:

Meenasarani Linde said:

Thank you for this elegant post. The connections you make are lucid and provocative, and make me want to reconsider Cole’s show in light of his connections with the Latin American songbook. Additionally, I’m struck by the modernist set design of his performance of “Quizas, Quizas, Quizas.” Owing more to Mondrian than trying to capture a postcard-like setting of the Global South, this mixture of a sonic Latin-inflected transnationalism with a visual minimalism, also resonates with Lynn Spigel’s work on television and modern art, specifically Ellington’s Black Atlantic created in the TV special, A Drum Is A Woman. As Shane Vogel has also worked on this special, especially the importance of dance, I wonder how a consideration of dance on television as it relies on the visual and the sonic, would impact a reconsideration of other black televisual performances in the 1950s as well as today? Keeping in mind how Katherine Dunham was also invested in the project of making diasporic and transnational connections, as well as education, what other performances are there to be excavated from tv history that are part of this circulation? How does the movement of bodies on screen connect to a body politic or public if at all? This post excites me, as Gray asks us to look past what could be nostalgia for exotica, and consider television as that which can look past the confines of the nation and the racial order.

-January 30th, 2012 at 9:22 pm

Elma Krom said:

thanks admın very nice….

-February 21st, 2012 at 4:40 am

real estate agent in india said:

This is a really good post. Must admit that you are amongst the best bloggers I have read. Thanks for posting this informative article.

-February 22nd, 2012 at 6:20 am

Please feel free to comment.