Ranks and Files: On Metacritic and Gamerankings

Peter Krapp / UC Irvine

While media studies usually approach computer games either via media history or in terms of ideological critique, my question is what influences game development cycles. Here, I take a closer look at the role of Metacritic (http://www.metacritic.com) and Gamerankings (http://www.gamerankings.com), two aggregators of game reviews that became influential in the industry – to the point of being used in employment contracts to calculate salaries and bonuses.

Since 2007, the US computer game industry boasts about surpassing cinema and popular music in annual dollar volume. The $19 billion market in 2007 (three times as large as a decade before) was half software and half hardware, with consoles and mobile devices taking a larger share than computers and displays. While the music industry shrank by 10% between 2002 and 2007 and the film industry remained flat, games saw growth of over 28%. But of the $60 you pay for a new game, 25% is the profit margin of retailers, between 15% and 20% royalties and licenses (for instance for intellectual property from the realm of sports, comics, or movies), 10% reserves for complaints, loss, or theft, 10% to 15% amortize investments in software (such as the Unreal or Massive engines), and often about 10% is due to hardware manufacturers. After packaging and distribution, only 20% of the retail price goes into developing the game. Yet development expenses have grown faster than retail prices. A 16-bit game cost about $50,000 to make, while increasingly complex graphics and higher expectations for interactivity in newer games drive up development costs: on average, Playstation games cost $2 million, Xbox titles between $3 and $7 million, Wii games $12 million. Current computer games and those for the newest console generation (PS3, Xbox360) can run up development costs of $20 million, and some ambitious titles devour much more.

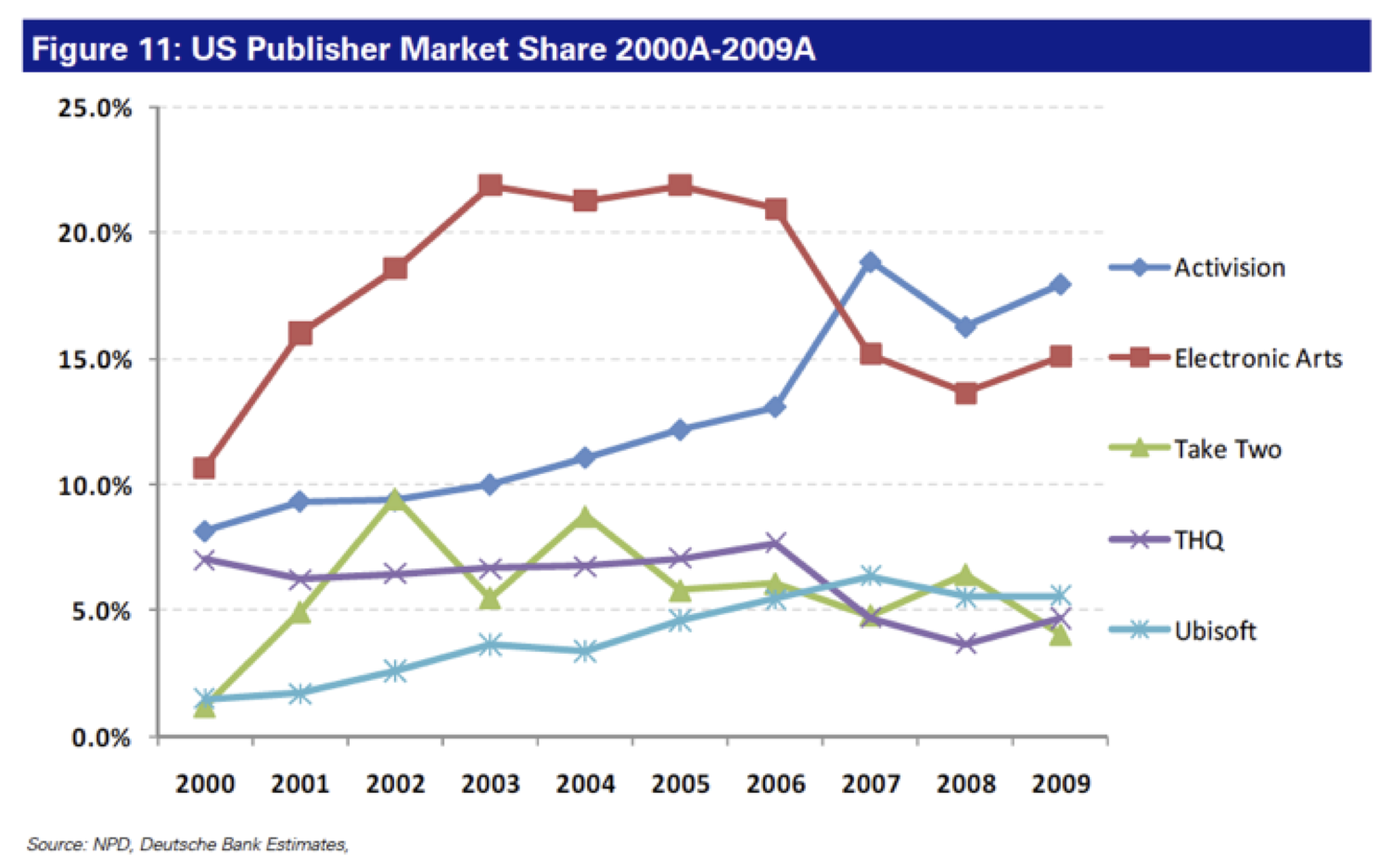

Since 1997, the market share of Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo has fallen from 44% to 17%, of which Nintendo has 10%, Sony and Microsoft between 3% and 4%. The four large American third-party developers Activision, Electronic Arts, Take Two, and THQ grew from 16% to 47%; EA alone has 24%, Activision Blizzard 20%, Ubisoft 6%. As former industry titans like Disney or Sega faded, new names like Valve entered the fray. Third-party developers can port games to several consoles, as Take Two did with Grand Theft Auto or Ubisoft with Assassin’s Creed, while Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft can discount hardware to stimulate software sales. Though the last development cycle saw many low scoring titles available for the Playstation, now Nintendo’s Wii and DS are the rare niches where game quality does not correlate directly with sales volume. Electronic Arts, Activision, and THQ used to rely on a broad array of niche products, often aimed at young at children or casual players; now major hits drive the industry. A major reason why Electronic Arts dismissed a tenth of its employees in 2009 to save $120 million is the fact that advance reviews of new products have increasingly influenced sales.

Unlike music criticism or film reviews, usually informed by an overall perception of the whole work, game journalists report without having fully explored all possible scenarios of a new title. Both Metacritic and Gamerankings belong to CNET (part of CBS Interactive since 2008). These websites turn reviews in a range of game magazines into an aggregate score, normalizing the rating systems of all publications into one scale. Scores are often posted before sales data become known – hence the influence scores exert in the industry and on Wall Street. For example, when Spiderman 3 came into stores on a Friday in May 2007, the lukewarm reception by critics (50/100) caused Activision’s stock to drop 5% that day, with further losses the following week. But in August of the same year, Bioshock received almost perfect early scores (96/100), and the stock price of Take Two rose 20% in a few days. As Activision CEO Robert Kotick disclosed, a study of 789 games for the Playstation 2 in 2005 showed a correlation between aggregate advance grading and sales volume; for every 5 percentage points above 80/100, Activision saw sales double. “Everyone wants 85 or better,” as LucasArts president Jim Ward told the Wall Street Journal in an interview.1 Activision and Take Two made Gamerankings and Metacritic scores part of their employment contracts, and industry partners like Warner Brothers for instance calculate licensing fees for games based on movies in relation to review scores: better games mean lower licensing fees, worse games mean higher bills to offset volume and any impact on the intellectual property’s reputation.

The dominance of rankings continued until spring 2011, when Homefront, a THQ game that has North Korea attack the USA in the year 2027, sold well despite bad critiques. When the first negative reviews appeared, THQ’s stock fell 21% in a day, yet sales figures bucked the trend. Metacritic calculated an aggregate grade of 72/100 – twelve of the first 28 reviews had good things to say about Homefront, but the majority saw a flop, with grades ranging from 40 to 93. Nevertheless, Homefront continued to sell well, and soon allowed THQ to recoup its investment at 2 million copies sold.2

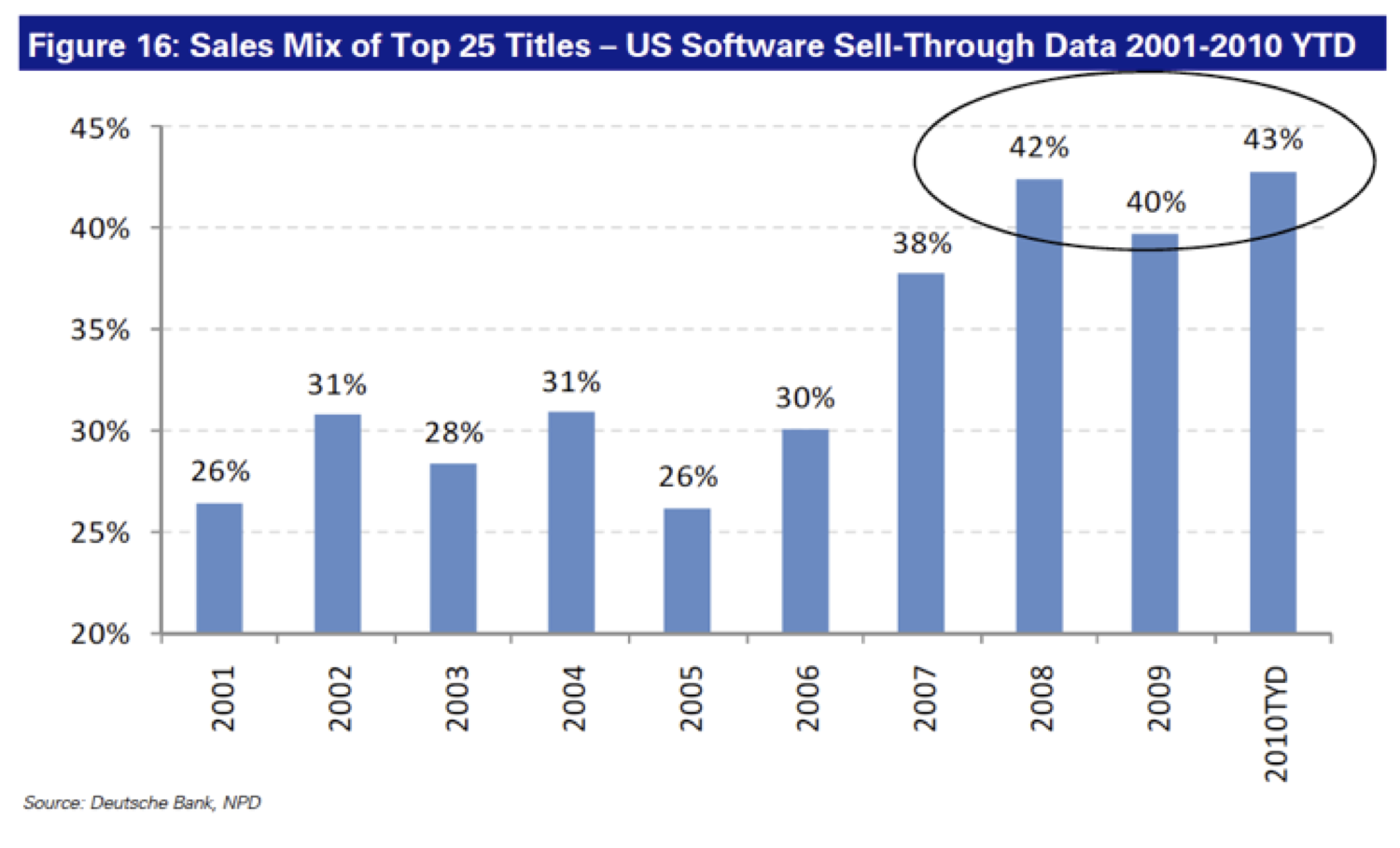

A closer look at sales data will help interpret the phenomenon. While film criticism rarely reflects the taste of the broad public, and music criticism has little in common with the pecking order of the charts and heavy rotation playlists, the game industry sees a direct correlation between game reviews and sales. Games with the highest aggregate scores – though these are merely the first impressions of a few dozen journalists – sell three times as much as games scoring between 80 and 90, and those again sell twice as well as games with an aggregate score between 70 and 80, while titles scoring between 60 and 70 only sell half as often as those between 70 and 80. A mere 4% of all titles sold between 2000 and 2006 were responsible for a third of all revenues, and a quarter of all titles represented 86% of industry revenues. In longitudinal studies, UBS (2007) and Deutsche Bank (2010) analyzed 1605 games. They found that the 3% scoring above 90 (50 titles) sold more than the rest of all games together; 23% received aggregate scores of 60 or lower.

Comparing the scores of their major titles shows that Activision did well with Call of Duty, Marvel Ultimate Alliance, Tony Hawk and Guitar Hero, while film adaptations like Spiderman 3, Shrek 3 and Transformers sold far worse. EA could count on Madden Football for 20% and on Need for Speed for 9% of revenues, while Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings made far less. CEO John Riccitiello blamed rankings: “We did not have any internally developed breakaway titles and none of EA’s internally developed titles reached a Metacritic rating of 90 or greater.”3 Take Two relied on a single franchise, Grand Theft Auto, for more than half of all earnings, while titles like Midnight Club and Max Payne were worth a lot less. In the same period, THQ counted mainly on licenses from Pixar, Disney, Nickelodeon and World Wide Wrestling, and titles like Spongebob Squarepants, Scooby Doo, Rugrats, Finding Nemo, and Power Rangers showed less of a correlation between reviews and sales. Yet the trend is clear: a decade ago, the 25 top sellers took a quarter of the market, in the last few years the 25 top sellers took over 40% of the market. The result is that an increasingly narrow range of games tempts a hit-driven industry to place ever larger bets on major titles, in pursuit of that elusive high score.

Image Credits:

1. Screen capture from gamerankings.com

2 & 3. Deutsche Bank Research, October 31, 2010.

Please feel free to comment.

- Nick Wingfield, “High scores matter to game makers too,” Wall Street Journal (20. September 2007), http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119024844874433247.html

Compare Joe Dodson, “Mind over Meta,” GameRevolution http://www.gamerevolution.com/features/mind_over_meta

[]

- Matt Peckham, “Homefront Reviews torpedo THQ stock price, Metacritic broken,” PC World, March 16, 2011; Alex Pham & Ben Fritz, “Bad reviews of Homefront send THQ shares tumbling,” Los Angeles Times March 16, 2011. See also Alex Pham, “THQ may profit from Homefront video game despite poor reviews,” Los Angeles Times March 26 2011. [

]

- Matt Martin, “Riccitiello: ‘Short-term pain’ necessary for further growth”, Games Industry International (February 1, 2008) http://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/riccitiello-short-term-pain-necessary-for-further-growth, compare Andy Chalk, “Riccitiello Won’t Dodge ‘Short-Term Pain’ At EA”, The Escapist (February 1, 2008) http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/81115-Riccitiello-Wont-Dodge-Short-Term-Pain-At-EA [

]

very good post – but the landscape just changed again with THQ going bankrupt: http://www.g4tv.com/thefeed/bl.....ore-games/

Aw, this was a really nice post. Taking a few minutes

and actual effort to make a superb article… but what can I say… I put things off a whole lot and

never seem to get anything done.

Thanks for the comments – due to the FLowTV format I had to cut away a lot of things I wanted to say, but in the end I like the succinct style of this site. I’ll come back to some of the omitted angles in my next post, promise!

Pingback: Criticism vs. Reviews | morbidflight