Looking at Rock Stars

Thomas Swiss / University of Minnesota and John Barner / University of Georgia

I take photographs to see what something looks like as a photograph.

—Garry Winogrand, photographer

These days, people only know my name. They don’t know what I do. I’m just a name.

—Marianne Faithfull

In Part One of this Flow column, we discussed how the modern portrait can be many things—a commodity, a canvas, or a confession. Portraits reflect larger archetypes that progress through the ages and reveal themselves to us in similar poses and themes. In this part, we examine how these similarities present a unique mirror to the psyche and the myth-making that occurs in the iconography of popular culture and its objects: photographs of actors, models, politicians and rock stars. As in Part One, we have assembled photographs and their stylistic antecedents and examined them as if they were parts of a contiguous whole.

Haunted

Portraits partake of the artificial nature of masks because they always impersonate the subject with some degree of conviction. Personhood, strongly attached to names, faces, bodies, and roles, can be understood as a metaphor for a particular intersection of social relations. What is left to the individual or to the artist portraying them is a matter of choice, perhaps an attempt to foster the pleasing deception that either of them is free. This alerts us to a problem in how we understand a photograph; the shifting distinction between its function as an image and its assumed value. In many ways those photographs deemed to have the most value are the least functional, and vice-versa.

Photographs are placed in categories (or genres) that codify their terms of reference and status. An ‘art’ photograph involves an entirely different set of assumptions from a ‘documentary’ photograph; all part of the complex web of interrelationships within which any photograph is suspended. The extent to which so much photographic practice has been haunted in its development by what has been termed ‘the ghost of painting’ is crucial, for photography established, from the outset, genres and hierarchies of significance related to painting. It institutionalized the artistic and professional aspects of its meaning in terms of an academic tradition.

Someone for ‘Something’

To take someone for a ‘something’—a great artist, ‘beauty’, leader or scientist—is to place that person within categories established by consensus to locate members of a society in familiar roles by which they are presentable and knowable. The denotation of someone as ‘the person who is something’ adopts the meta-language of the social act in defining identity, equivalent in its value to the person’s name. Like all ‘portraits’, images remain framed within a context that asserts simultaneously individual significance and attendant myths. They promise access as they declare privilege. And consistently, the ‘portrait’ hovers between extremes: on one hand the passport image, an identity card which stamps itself as an authoritative image; and on the other the studio portrait, which is offered as the realization of the photographer’s definitive attempt to reveal an interior and enigmatic personality that exists solely within the imagination of the viewer.

The Imagined Subject

Fig. 2: David Crosby

The imagined subject in rock photography is displayed as caught up in narcissistic fascination with the mirror image that, with its connections to curiosity and desire, draws the viewer further in, placing themselves in the role of the musician-as-object. One example can be seen in Figure 2, a portrait of David Crosby, then with the Byrds. Crosby is looking over his shoulder into a mirror at his reflection. His eyes are fixed on the image of himself, dressed in the dandy-style clothing the band wore at the time, sporting a satisfied, confident expression. Since the angle obscures Crosby’s “real” face, the viewer is drawn into the reflected image to glean the details of the photograph. We can compare this with Caravaggio’s famous painting Narcissus (see Figure 3), illustrating the egotistic satisfaction and longing present in both the classical Greek myth and the myth of the ever-confident rock star “attitude.” In Lacanian psychoanalysis, the mirror’s reflection and its recognition are a metaphor for ego formation—considering not only the self as it is but also an ideal self—what we most want to be. The point of the ego ideal, for Lacan,

is that “the subject will see himself, as one says, as others see him—which will enable him to support himself.”1

Larry Rivers’s Double Portrait of Frank O’Hara (1955) presents a “doubled” portrait—a simultaneous self and ideal. Through subtle movements of the head and the visual angle of the painting, O’Hara is seen as placid and composed in the right hand panel (see Figure 4) and, with arched eyebrows and a penetrating gaze, much more sinister in the left hand panel. These differences in tone and mood continue in repeated viewings of the portraits, where one begins to show a hint of a smile, the other betrays a downturned countenance, almost a frown. Where the eyes of one are calm, the others seem to burn with inarticulate rage. These two images (which are facets of one image, one subject, one “self”) portray two disparate and irreconcilable aspects of the same personality, indicative of Lacan’s transformative anxiety of the uncanny double experience.

We call the Rivers portrait “uncanny” in that it captures this dichotomy, whereas other exemplars of Pop Art style, such as Warhol’s duplicated portraits of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, seem to, by the very nature of their photorealistic duplicative process, create vacuous space, and rendered devoid of the vaguest possibility of viewer identification.2 That their difference is so subtle, and may not even be evident upon every viewing, is precisely what makes the doubled image an uncanny image of binary opposition.

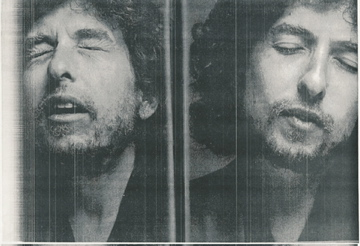

Often, the cultural industry of popular music exists to both beckon and keep apart divergent elements away from the “rock icon” ego ideal, as is seen by the dual portrait of Bob Dylan (see Figure 5). In the Dylan portrait, the difference between each is exaggerated and heightened where the previous double portrait of O’Hara is more subtle. Dylan is seen, on the right, as peaceful and calm, with softly closed eyes, with his head tilted slightly and lips puckered as if in a kiss. On the left, Dylan is seen as if in either orgasmic ecstasy or anguished pain, with mouth open, eyes tightly closed, head held

rigidly stiff. The viewer’s attention may seem unable to stay fixed on just one of the images, and indeed the viewer may not be able to reconcile the two images as one, thus increasing the anxiety and tension that are characteristic of the moment of displaced, uncanny identification. As Roland Barthes notes, the moment of identification with a photograph is always split and never reconciled, the moment frozen in time at a point of pivotal “catastrophe”—a catastrophe which has always, already occurred, and always will occur.3

Image Credits:

1. Marianne Faithfull

2. Janet Leigh

3. David Crosby (1966), photograph by Philip Townsend, from author

4. Narcissus, by Carvaggio

5. Frank O’Hara

6. Bob Dylan (1976), photograph by Lynn Goldsmith, from author

Please feel free to comment.

- Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans., Alan Sheridan. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991., 268. Emphasis in original. [↩]

- Cf. Steven Shaviro, “The Life, After Death, of Postmodern Emotions” Criticism 46, (2004): 125-141. [↩]

- Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981., 96. [↩]

real attitude!!!

http://www.freehotmusic.org/in.....h-attitude

Pingback: Sing Your Life: Morrissey’s Autobiography | ANOBIUM