Formatted to Fit Your Screen

Jonathan Sterne / McGill University

From time to time, I find myself having a bizarre genre of conversation with colleagues in other fields—usually from those untouched by Anglophone media and cultural studies traditions. When television comes up, my interlocutors declare “I don’t watch television. I don’t even have a television.” This would seem like standard-issue distinction behavior (cue the Bourdieu 1984), except what comes next undermines that reading. Invariably, my interlocutors begin to catalogue all the shows they like and watch on other platforms, usually involving a computer (since this conversation happens often with administrators, The West Wing is frequently mentioned). For most of the medium’s history, watching television meant watching a television, a sensibility still well-established in practical reason and everyday conversation. But of course, this is no longer the case. We now live in an in-between moment, when it is possible for educated and thoughtful people to spend many hours of their lives watching television shows and yet not think of themselves as watching television.

While it is tempting to consider this a problem of self-assertion and taste on the part of the person making the “I don’t watch television” claim, the ambiguous semantic space between watching television and watching a television gestures back to a long and fruitful line of inquiry for television scholars. For that space gets at the problem of defining television. The productive confusion over the conditions under which one watch television would seem to emanate from the ambiguous status of the medium at this moment in its development, or more accurately, its dilution, as has been well-documented by many other Flow writers.

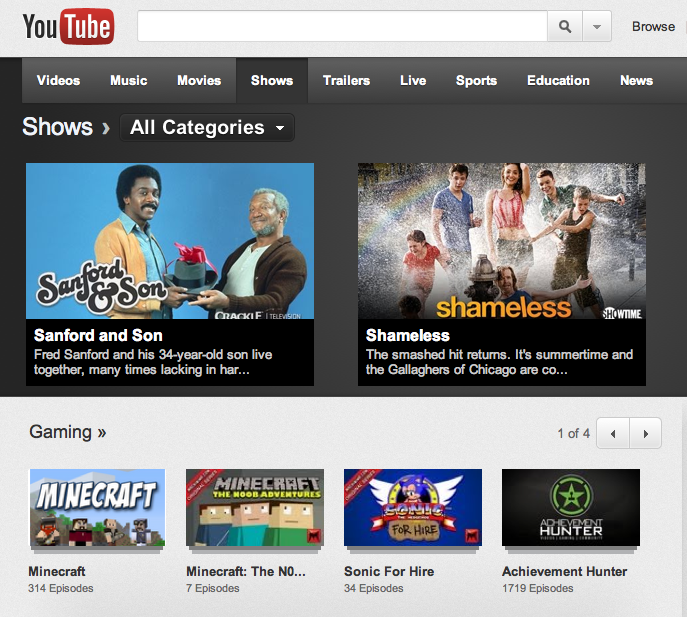

I use the term diluted deliberately. For most of its history, television has been thought of as a medium. For most of the 20th century, the word media has been the preeminent technological figure for thinking about communication. But today, other technological forms of communication may matter more in many contexts. I just finished a book on a format, the mp3, that I argue matters much more than a “new medium” of sound reproduction at this particular moment. We can put our ideas about television through a similar filter. It is not that television is no longer a medium, it is that its status as a medium has lost density and gravity—in a word, its status as a medium is diluted. This is why we can read announcements in the paper that YouTube is trying to be “more like television” when it already contains television.1 Today, television’s relationship to various infrastructures, formats, platforms and protocols may matter more than its relationship to itself as a coherent medium.

Although I’m putting a presentist spin on the question, the problem of defining television has dogged its intellectual history, from Leo Bogart (1956) and Raymond Williams (1992) on down to Anna McCarthy (2001). As James Hay has argued, there is a dual tendency in academic television criticism to treat television as a medium like any other, or a medium like no other; one instrumentalizes television as anything; the other deifies it as everything (2001, 205). Riffing on Williams, he writes that we should consider television

as an assemblage of practices, as a social technology dependent on and instrumentalized through a broad array of practices and technologies. Within the interplay of exchanges, the televisual refers to mechanisms linked by/to particular sites and by/to other mechanisms at these sites, and it refers to mechanisms adapted to particular tasks of linking/delinking subjects and places. Thinking about the televisual in this way requires not only a different logic of mediation but a different understanding of TV as site. TV criticism’s focus on the internal properties of texts and of their subjects, TV studies’ preoccupation with the distinctive features of the medium or its audience, generalize the site of television or dwell on TV’s separateness as both identity and sphere/site. They have tended to see the site of TV as language and the psyche or to ascribe it to culture as a distinct and separate sphere in social relations and history. Television, I propose, matters or matters differently at different sites (211).

Reading back eleven years, this passage looks positively prophetic against the profusion of platforms, protocols, technologies and sites through which one might engage with television today.

Another set of issues arises if we set Hay’s definition of television next to Lisa Gitelman’s definition of media. For her, media are:

socially realized structures of communication, where structures include both technological forms and their associate protocols, and where communication is a cultural practice, a ritualized collection of different people on the same mental map, sharing or engaged with popular ontologies of representation [….] If media include what I am calling protocols, they include a vast clutter of normative rules and default conditions, which gather and adhere like a nebulous array around a technological nucleus […] so telephony includes the salutation “Hello?” (for English speakers, at least), the monthly billing cycle, and the wires and cables that materially connect our phones. E-mail includes all of the elaborate layered technical protocols and interconnected service providers that constitute the Internet, but it also includes both the QWERTY keyboards on which e-mail gets “typed” [again, for English speakers] and the shared sense people have of what the e-mail genre is (Gitelman 2006, 7–8).

Gitelman goes on to qualify her definition further, pointing out that the technological nuclei of media are not permanent or stable over time, and neither are the protocols or practices associated with media: “it is better to specify telephones in 1890 in the rural United States, broadcast telephones in Budapest in the 1920s, or cellular, satellite, corded and cordless landline telephones in North America at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Specificity is the key” (8). As far as I can see, Hay and Gitelman are singing the same tune, and by this measure, they have given us a more nuanced definition of television and of medium.

A careful reading shows that the definition of medium is itself historically specific. E-mail works as a medium in Gitelman’s definition from a contemporary perspective, but in 1974, it would likely have been subsumed under computers or some other hardware-based definition, despite the fact that mechanical and electronic media have always existed somewhat independently of their technological forms: sound recording and sound film both existed in several technological forms at once throughout their histories (this is well-understood in sound studies, but is only beginning to be accounted for in cinema studies; see, e.g., Acland and Wasson 2011).

The connotative shadow of hardware looms large over any definition of media today, even though media forms, like e-mail, seem ever less attached to any specific form of hardware (since you can do your e-mail on a computer, PDA, mobile phone, kiosk, or for that matter print it out and treat it like regular mail—and may in fact do all these things in the same day). Looking back historically, writers tend to associate telephony with telephones, radio with radios, film sound with cameras and movie projectors, sound recording with phonographs, tape recorders, CD players, and portable stereos. This is why television can be conflated with a television set in everyday conversation. Yet the mediality of the medium lies not simply in the hardware, but in its articulation with particular practices, ways of doing things, institutions and even in some cases belief systems.

So what binds together television on a TV set, a game system, a laptop, a smartphone and a tablet? The institutional and technological weight we normally associate with the idea of television as a medium seems too heavy to sit comfortably in all this different hardware, especially as the hardware becomes more and more of a variable. The ideal of television as a kind of text is equally unsatisfying if we think about textuality purely interpretively (rather than also considering its conditions of production and circulation), for what inside the text ontologically separates shorts made for YouTube from television shorts on YouTube?

We will need a handful of middle-range concepts to navigate this space, and I will offer but one in conclusion: format. Like media, the term is certainly baggy. It can designate a file format (.wmv, .doc, .mov); it can designate the sensual characteristics of what is seen (color; high-definition; stereo or 5.1); and in television, it can also describe programming trends and practices (“presented in a talk-show format”). But the form offers a way into thinking about the combination of standards, technical routines and sensual characteristics of those things we call television. Writers have often collapsed discussions of format into our analyses of what is important about a given medium. McLuhan’s claims about “coolness” and TV came from descriptions of screen size and color (McLuhan 1964, 22), which today seem less like fixed aspects of a medium and more like hardware variables (though we should give him credit for using “definition” to talk about the sensory dimensions of TV already in 1964). I am suggesting that an emphasis on format helps us separate our conceptions of media from their manifestations as (what we now call) consumer electronics. Format points us back to the conditions under which mediality occurs.

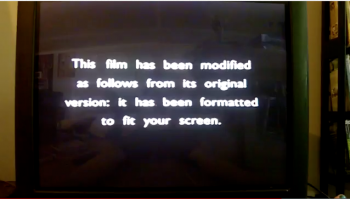

To take an obvious example from the present moment, consider the digital spectrum and high-definition broadcast. Since the 1940s, North American analog television has been filmed and broadcast with a 4:3 horizontal / vertical aspect ratio. A 1936 report by the U.S. Radio Manufacturers’ Association Television Committee first suggested the 4:3 aspect ratio, which was then set in U.S. Policy by the National Television Standards Committee in 1941. 4:3 was chosen because that was the aspect ratio for Hollywood films. In part as an attempt to compete with television, Hollywood stepped up ongoing efforts to adopt wider screens (Boddy 1990, 34–35; Gomery 1992, 238–46). Thus, to this day North American analog televisions have a 4:3 aspect ratio, and audiovisual content from other media (such as film which is often 1.85:1) or formats (such as high definition, which is 16:9) is reformatted to fit the 4:3 TV screen when we watch it on analog TVs—either through “letterboxing” or through re-editing. Cue the McLuhan (1964) and Bolter and Grusin (1999) about media containing their predecessors.

This disclaimer, once ubiquitous on videotapes of Hollywood films released to VCR, is miraculous for the layers of meaning it contains. It is meant to signify editing to change the proportions of the image. But in fact by definition anything that appears on television screens has been “formatted to fit your screen”—it has been subject to a host of data processing routines and is presented in a particular sensuous form. If the image was not formatted to fit your screen, you wouldn’t see it on your screen. You may not like how it fits on your screen, but that is a separate matter of playing with the aspect ratio on your remote control. Thus, format is a place where aesthetics and storage and transmission come together, as anyone who watches HD content and reruns of shows made for what we now call standard definition (that used to be just television) can attest.

When it goes the other way, television’s formatting and formatted qualities are actually more pronounced. HD shows are compressed and chopped up to be seeded over torrents. They are recoded to appear in variously-shaped video windows in VLC player, Quicktime or Windows Media Player, or transcoded to be streamed off YouTube, Vimeo, or Critical Commons. But because of their combined institutional and aesthetic histories, they are still somehow television. I am not proposing format as a replacement for medium. But I believe it is one of a handful of words—infrastructures, platforms and standards are a few of the other places we need to be poking around—useful for thinking through television in its condition as a diluted medium, and in turn diluting the concept of medium as a central touchstone of how we imagine the technological dimensions of communication. In this sense television remains a typical medium, for while TV retains its specific cultural, technological and institutional histories and trajectories, all media today are more or less diluted.

Image Credits:

1. Josh Bancroft via Flickr

2. Screen capture from http://youtube.com/shows, 1/23/2012

3. franciscominciotti via Flickr

4. Screen capture from YouTube, “Opening to Space Jam (1996) VHS,” provided by author

Please feel free to comment.

Sources Cited

Acland, Charles, and Haidee Wasson, eds. 2011. Useful Cinema. Durham: Duke University Press.

Boddy, William. 1990. Fifties Television: The Industry and its Critics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Bolter, Jay and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bogart, Leo. 1956. The Age of Television: A Study of Viewing Habits and the Impact of Television on American Life. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Gitelman, Lisa. 2006. Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gomery, Douglas. 1992. Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States. London: BFI.

Hay, James. 2001. “Locating the Televisual.” Television and New Media 2 (3): 205-234.

McCarthy, Anna. 2001. Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space. Durham: Duke University Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Williams, Raymond. 1992. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

- The “more like” in this case has to do with keeping people on the site for the purposes of raising advertising revenue. [↩]

I really like this column, especially for its addition of “format” to the critical vocabulary for understanding TV as a compliment to “medium.” As a long-time reader of your blog, I have been anticipating your MP3 book and I’m excited that it’s coming out soon.

In our recent book, Legitimating Television, Elana Levine and I consider some of the same topics you raise here. We write about people who watch TV denying that they watch TV, aspects ratios, the proliferation of new ways of watching, and Gitelman’s definition of medium. But we apply different terms and draw different conclusions. I hope a comparison of our approaches might be productive.

What you explain as the dilution of the medium we discuss as convergence. And while you put aside the issue of taste in your introductory remarks, we see it as central to television’s shifting status.

To think of TV as a diluted medium suggests that a medium may be weak or intense, and that TV in the past was stronger or more pure than it is now (you say it has lost density and gravity). Perhaps it is true that TV’s identity was more stable in the past, though its history is one of constant technological renewal — through set technologies such as color and projection, remote control devices, videotape, cable, etc. We argue that in the past decade, television has been intensifying its convergence with other media, which is a different idea from dilution. Not just in terms of technology but also in terms of experience and cultural status, television has been converging with computers, the internet, cinema, video games, and other media. We quote a Netflix executive describing television becoming part of the movie-viewing experience. When both movies and television shows flow through the same browser window, the experiential aspects of each one become less distinct. But the medium of TV isn’t necessarily diluted by this process in the popular imagination. Even though some people might not consider watching TV via Netflix “watching television,” the identity of shows like Mad Men as television persists. In some ways, TV’s identity is intensified as television’s cultural status has been upgraded, in no small part as a product of this kind of convergence. We found many examples of critics arguing that TV is better than ever before and relating this to new technologies like DVDs and DVRs — in such discourse, TV has simply “gotten better” and thus more deserving of attention and praise. (We argue that this only works by the promotion of one kind of television at the expense of another — legitimated TV, with its adult, masculine, and upscale appeal, requires the negation of its Other: TV as feminized mass culture of the past.)

The distinction between medium and format might be productive for scholarship, but in our analysis of popular, trade, scholarly, and televisual discourses we didn’t observe that television’s status as a medium was weakening or becoming less distinct — becoming something more like a cluster of formats, as you use the term. It has been shifting in the direction of cultural legitimacy, and these very techologies that you relate to dilution we see as part of the discursive shift toward television’s higher status. These technologies are seen to be giving viewers highly valued agency, and to be making for a more artistic medium visually and in other ways. The issue of taste is central because it marks the transformation of TV into a more respectable medium like cinema (or literature).

Most of all, you seem especially interested in how scholars might define television. Our concern is more with how a wider culture understands TV and its significance in everyday life. I hope we’d agree that both of these are worthwhile pursuits, and that one will inform the other.

Anyhow, thanks for writing this!

The overlapping analyses yet divergent conclusions of Sterne and Newman/Levine are revealing of the conundrum TV Studies faces at present. The divergence of views (dilution or enhancement) is, as Newman rightly points out, a result of very different starting points in analyzing the shifts in the status of television as a medium.

Sterne’s column clearly fastens on changes in television itself, and the intellectual discourses on it. In this sense, his argument for a serious rethink of the vocabulary through which we approach television is compelling, and very necessary. More importantly, it contributes to a more substantive engagement with the crucial shifts that are taking place in television and our (that is, academics) discourse on it.

Newman and Levine’s Legitimating Television rightly takes to task the spurious elevation of television by those who want to justify their passion for TV series in high cultural terms. Fair enough. But this criticism, which has been ongoing for sometime, including on this platform, does very little to further scholarship about the shifts in technology, the transformations in textual strategies, and consequently, newer perspectives on how to understand television today. In other words, by magnifying and (perhaps regrettably) over-publicizing the views of those who have never had any interest in television anyway (did we ever take the Mark Lawsons of this world as serious contributors to TV Studies?), the need for serious scholarship and sustained engagement with television’s dramatic contemporary changes risks being sidelined for a slanging match between parties ranged around two very suspect terms indeed: high and low culture. It also runs the risk of being cast as a defensive reaction by those wanting to maintain a disciplinary identity and its attendant privileges when the medium the discipline is founded on is refusing to be disciplined.

Sterne’s column neatly sidesteps this, maybe once necessary (defensive) gesture of bashing suspect over-valuations of television, and focuses instead on what challenges television poses for those of us interested in the theoretical, political, social and technological dimensions of this medium. The contemporary changes in television as technology, text, institution etc. are far too important to be framed in the tired discourse of either “quality” or a critique of it.

In “The Uses of Cultural Theory”, Raymond Williams eloquently and urgently argued that close attention to the formal characteristics of a text (and for us in TV Studies, to the concurrent shifts in technology and institutional structures) is crucial if we are not to dodge the way technology, aesthetics and a medium are intertwined. Developing a critical and contemporary vocabulary for understanding changes in TV today, and substantively engaging in analyses ranging from programming strategies of broadcasters to the minutiae of textual development in programs, are crucial to how TV scholars might contribute to the study of the medium. Let the guilt-ridden aesthetes who are busy justifying their love of television prattle on. Our job, it seems, lies elsewhere, and is far more important, politically, socially and institutionally.

The issue is thus one of emphasis rather than disagreement. Rather than focus on the spurious interests of those fairly uninterested in a scholarly analysis of television anyway, engaging productively precisely in the contemporary character of the transformations of the medium might be a far more enriching experience socially and intellectually.

Pingback: Book Review: Legitimating Television by Newman and Levine « Media Milieus

Pingback: The Future of Television? Sharon Strover / The University of Texas at Austin | Flow

Pingback: I’m reading The Future of Television? Sharon Strover / The University of Texas at Austin | william j. moner

I agree with your call for the inclusion of the word “format” as a part of our discussions on the nature of television and televisuality; how it can be, as you say in your post, “useful for thinking through television in its condition as a diluted medium, and in turn diluting the concept of medium as a central touchstone of how we imagine the technological dimensions of communication.” “Format” can also serve to define televisuality in a less physical/more textual way, especially when looking at global television trends and the adoption of TV formats across networks and borders. In Tasha Oren’s “Reiterational Texts,” she discusses how the use of format and format borrowing in the creation of television content is not only distinctly televisual, but also a location of, and system for creative energy in the production and also the reception of television.

This is isn’t a concept that can be applied to all television content, but it’s a useful way of conceiving of how so many tv shows borrow from and speak to each other, simply through the shared use of similar structures. The skeletal structure of a specific type of show can be transferred across networks, cable, the internet and national borders and allows for intertextual conversation between shows to occur through the format structure itself. While the discursive processes of genre often occur during the mode of reception, format borrowing occurs on the production end and allows for the same type of discursive modes between audiences and producers.

I think your discussion of the physical format concept can also tie back to your starting point of those who claim not to watch TV. Back when television flow was controlled by media companies, it seemed high brow to turn one’s nose up at being one the sheep who allows oneself to get sucked into the boob tube’s flow of information and propaganda– when there was no individual control over flow. Now, with the numerous evolutions that have taken place to put the individual in control, watching tv isn’t so vilified as a mindless, passive activity, because we can fast forward through commercials, start and stop at will, and if one chooses, only be exposed to “quality tv” through DVDs, Netflix, Hulu, On Demand, DVR, etc. We manipulate our flow by manipulating our format. However this also poses the conundrum in TV Studies that tends to glorify group viewing (golden age, 1950s, families and the nation watching together) over individual viewing, even though now, our age of control engenders more individual viewing. I think this is a Catch-22 that TV Studies finds itself in more and more, and the introduction of the term “format” as an essentially televisual quality (in both physical and textual nature) is one way in which we can grapple with this issue.

First, thanks to everyone for thoughtful replies — the comments are at least as good a read as the article. I’d meant to reply much sooner but each time it occurred to me, I was doing something else, like traveling.

I suspect that as a TV studies scholar my angles are somewhat marginal to the field: my first TV studies piece was on infrastructure, and I’m now cowriting a couple essays on color TV and the technical politics of perception. My interests in TV have always veered toward the technocultural, and that’s what drives this column. When I call television a diluted medium, I do so for two reasons related to the cultural form of television: 1) ALL media are diluted at this historical moment, and the ontological weight academics have attributed to them in the past now seems misplaced when the important historical changes seem to be distributed among infrastructures, platforms, portals, consumer electronics, formats, standards, protocols, and on and on. Changes in any one may be trivial, or may be the hinge in some bigger technocultural swing. But in media studies, anyway, there is still a tendency to focus on “media” which implies a certain hierarchy of scale when we discuss communication technologies. I’m saying we should explode those presuppositions about the scale or register of inquiry.

Of course “format” has other pedigrees in television studies, most notably textual and textural (the gamedoc, the half hour local news show, the YouTube promo, etc). Michael’s and Katie’s posts point to this other meaning of format. I certainly think it’s worth exploring, but they are clearly better prepared than me to carry out the work. I watch plenty of TV but have no chops or cred as an academic or otherwise TV critic, apart from this (which may in fact demonstrate I have no chops): http://bad.eserver.org/reviews......18PM.html .

Like Sudeep, I’ve pretty much bowed out of the high culture/low culture debates. I prefer to act as if things like TV (and popular music and and) are legitimate already. I realize that’s a luxury of not working in a heavily canonized humanities department (like literature or an old fashioned film studies program) but it’s one that I enjoy.

That said, there’s still a lot of sanctioned ignorance even among otherwise respected media scholars around the last 35 years of scholarship on TV. Especially when it comes to claims about interactivity and new media (ie, that the internet is active and tv is passive). But that’s for another time.

Sterne’s article regarding “format” and the medium of TV is interesting and creates an awareness that many people often overlook. For instance, Sterne explains how his colleagues unknowingly declared that they don’t watch TV or even own one. One could assume then that his colleagues do not watch TV period. However, they do actually watch TV. They just watch TV shows on a different medium (i.e. computer, phones, etc.) formatted to fit their screen. This is an interesting conundrum: What does it mean to watch TV? Should TV be defined by what you watch or on what you watch it?

If TV is defined by what you watch then the medium is not diluted in any way. As comments above explained, TV is intensifying by its convergence with other media. The Internet, which is accessible from laptops and iPhones allow people to connect and watch their favorite shows whenever or wherever they want (the ultimate remote control). If TV is defined on what you watch, then I argue that TV is still intensified by its convergence with other media. TV has the ability to do more than just watch TV shows. It’s constantly becoming more interactive—(it’s almost like a huge computer screen). Apple TV is one example. It allows you to watch TV shows, movies, listen to music, view pictures, etc., everything done on your laptop transferred over to your TV screen.

Sterne’s column makes one aware and think about what is really meant when someone says, “I don’t watch TV or own one.” The “dilution” is not in the medium itself; it’s in the direct and limited-1950s design link of only watching TV on TV. Thus, the dilution is in: Defining the medium. With limitless ways to use and watch TV, the concept of defining or redefining the medium of TV is necessary in the technology-obsessed, 21st century.

This is a very informative article about the changing ways people watch television. People today can watch television on their phones, computers, or tablets. It seems that the television set itself is losing its’ relevancy. I have friends that don’t have cable, or even own a TV set, because they are willing to watch a show online. In a way the changing of formats is a good thing: if you miss watching a show live, it is easier to catch up by watching it on a DVR or on the network’s website. Scripted shows like Mad Men are easier and more rewarding to watch in the order they were aired. On the other hand, competition reality shows like American Idol and Dancing With the Stars seek to get the live viewership. Watching reruns after I know who has won takes the fun out of the latter type of shows.

I agree that there is a sort of “dilution” when television is watched on another platform like a phone. I prefer to watch my television set when possible, because the screen is bigger and it is easier to flip a channel or use closed captioning. I find it hard to believe that YouTube was created only seven years ago – it seems like it has been around much longer. Watching shows online is a relatively new phenomenon, and I wonder what future changes will be made to accommodate television.

This is a very informative article about the changing ways people watch television. People today can watch television on their phones, computers, or tablets. It seems that the television set itself is losing its’ relevancy. I have friends that don’t have cable, or even own a TV set, because they are willing to watch a show online. In a way the changing of formats is a good thing: if you miss watching a show live, it is easier to catch up by watching it on a DVR or on the network’s website. Scripted shows like Mad Men are easier and more rewarding to watch in the order they were aired. On the other hand, competition reality shows like American Idol and Dancing With the Stars seek to get the live viewership. Watching reruns after I know who has won takes the fun out of the latter type of shows.

I agree that there is a sort of “dilution” when television is watched on another platform like a phone. I prefer to watch my television set when possible, because the screen is bigger and it is easier to flip a channel or use closed captioning. I find it hard to believe that YouTube was created only seven years ago – it seems like it has been around much longer. Watching shows online is a relatively new phenomenon, and I wonder what future changes will be made to accommodate television.