Stop Being an Elitist, and Start Being an Elitist

David Jenemann / University of Vermont

This year, a group of TV scholars from New England have been participating in a travelling symposium called “The Place of Television in the Academy.” At each of the stops on this roadshow, three or four of us hold forth about an issue in contemporary television scholarship. At the first of these events, held at the University of Vermont, it fell to me to tackle the question, “Is TV Culture?”

“Well, duh!” I said initially, “Of course television is culture.” But the more I thought about it, the more I realized what a thorny and perilous question this is. Of course television is culture, but the sort of culture it is for many of us who research and teach television in post-secondary institutions is widely divergent from the type of culture it is for the vast majority of viewers.

What do I mean by this? This year, Superbowl XLIV between the New Orleans Saints and the Indianapolis Colts was watched by an estimated 106.5 million viewers, making it the most watched single broadcast in US history. In setting this record, Superbowl XLIV surpassed the 105.9 million viewers scored by the final episode of M*A*S*H*, a record held since 1983. The success of the Superbowl might come as no surprise, given the pride of place sports has in the American cultural landscape. What is surprising is how long M*A*S*H* held onto its title, especially when considering how dominant televised sporting events are in the global television landscape.

In fact, throughout the rest of the television-watching world, the most watched broadcast in nearly every nation is invariably a sporting event. In the UK, it’s the 1966 World Cup Final. In Canada—perhaps predictably—it’s the gold medal men’s hockey game of the 2010 Vancouver Olympics (Canada 3: US 2). In Germany, France, Italy, Australia, and pretty much everywhere else, the sport may differ but the story is the same. In fact, the US, with a situation comedy holding its top ratings slot, was one of the notable exceptions to this rule, the other being China, whose most watched show is the state sponsored CCTV Spring Festival Gala.

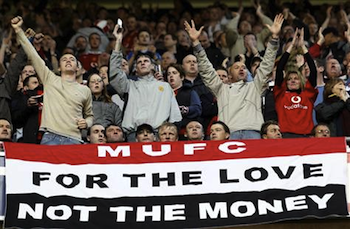

If you remove the national context, the dominance of sports broadcasting is even more striking. On a weekly basis, Premier League Football (British soccer for stateside readers) is broadcast to 600 million homes in 202 countries, and in November 2007, an estimated 1 billion fans watched a match between Arsenal and Manchester United.

This love of sports is having a profound effect on the television industry, and not merely in terms of advertising revenue and the sale of broadcast rights, which are enormous, but in its impact on sales of television technology. What’s driving the adoption of HDTVs? Football—on both sides of the Atlantic—and Sony Playstations (whose popular NFL Madden game now requires HD for access to all features).

This link between sports fandom, HDTV technology and viewership has reached something of a decadent extreme with the opening of “Jerry’s World,” the Dallas Cowboy’s new stadium, which features the world’s largest 1080p HDTV, with screens weighing 170,000 pounds, measuring 53 yards wide and featuring 11,393 square feet of viewing space. In fact, taken altogether, the various HDTVs in Cowboy stadium whose job is to display the game threaten the game itself. Fans have already complained that they can’t see the live action on the field, and in 2009, Tennessee Titans punter A.J. Trapasso had his punt blocked by the central HD screen.

But this link between the popularity of sporting events and the explosion of television technology has always been part of the TV equation. In the immediate wake of the 1947 World Series between the New York Yankees and Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers, consumer’s bought 25,000 television sets. Before that event there had been fewer than 75,000 sets sold since 1939. In the months following, the total number of receivers doubled every four months. Of this World Series, Variety wrote that it “proved conclusively that [TV] is better than radio — and even better than a seat on the first base line — when it comes to dramatic moments.” 1

It should be clear then what sort of fans determine the development of the industry and constitute a large part of what makes up TV culture. But it’s equally clear that these fans aren’t the fans that write scholarly TV criticism. A casual survey of the textbooks and readers commonly assigned in television courses turns up not one single chapter dedicated to televised sports. Let me emphasize this: In TV studies sports are all but completely missing, ignored, unexamined, and forgotten. Whatever sort of fans TV scholars are—they’re not sports fans.

So what does the academy say about TV culture? On the one hand, scholars like Michelle Hilmes argue that television’s appeal is in part predicated on identity: “Television has always been associated with the feminine, because of its position within the home and its historically greater appeal to female audiences. Part of its status as low other has to do with this association.”2

On the other had, there is the argument espoused by Jason Mittell that a key measure of television’s value is its “narrative complexity” where quality programs “convert many viewers to amateur narratologists… Narratively complex programming invites audiences to engage actively at the level of form as well, highlighting the conventionality of traditional television and exploring the possibilities of both innovative long-term storytelling and creative intraepisode discursive strategies.” 3

Both of these accounts of TV culture are persuasive within a narrow context but are ultimately unsatisfying when confronted with the sheer magnitude of sports broadcasting’s influence on the medium. Hilmes’ account of TV as a gendered medium—hence the province for a scholarship informed in part by identity politics—misses out on this influence completely. Given the demographics of sports television, TV was never—if ever— simply of greater appeal to female audiences. Hilmes’ assertion may be true of narrative television but not of television taken as a whole.

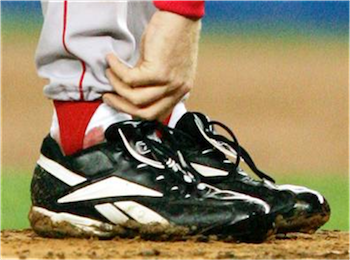

And this leads to the problem with the narrative complexity argument. First, even if its true that what constitutes quality television is narrative complexity, then ignoring sports speaks ill of TV scholars. As anyone who watched the 2004 ALCS between the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox can tell you, there’s at least as much narrative complexity and substantially more drama in a Major League Baseball season (which has 161 regular season “episodes”—or games) than there is in a season of Mad Men. For that matter there is also more forensic interest in Curt Schilling’s bloody sock than there is in a season’s worth of CSI cadavers. And rather than take the position that sporting events are “reality” we should analyze and embrace how these athletic dramas are carefully scripted and aesthetically constructed to encourage the same types of active engagement and formal analysis Mittell celebrates.

But to my mind, an even bigger shortcoming of the narrative complexity argument—one acknowledged by some of its proponents—is that it doesn’t speak well of the expertise required of a TV professor compared to that of the writers of Television Without Pity or The Onion’s TV Club. Indeed, if narrative complexity is your gold standard, the only difference between professional TV scholarship and your average blog is that the blog is often better-written, wittier and shows a greater grasp of history than most peer-reviewed essays.

As I see it, an intractable problem with the way that academic TV culture is now configured—somewhere between a fandom predicated on identity and narrative appreciation—is that it privileges a perpetually middlebrow position. Essentially, academics as TV fans write about what makes them feel good, gives them pleasure and congratulates them for their taste. But as far back as the 1930s, Frankfurt Schoolers like Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse were already warning us about “the affirmative character of culture”—popular culture that congratulated us for our “soul” while letting us off the hook for contributing to culture’s alienating effects.

But if anything is more notably absent from TV scholarship than sports broadcasting it is a thoroughgoing analysis of the contribution of the Frankfurt School beyond the reflexive dismissal of Horkheimer and Adorno’s “Culture Industry” essay and its perceived elitism. Just a little bit of reading beyond that essay (and maybe a closer reading of it) would go a long way toward dispelling that claim. But even if critics like Adorno are elitist, given how Aca-fandom has created its own canon and looks down its nose at (or worse outright ignores) certain cultural forms like sports broadcasting, we could use a little of Adorno’s elitism in the discipline today. In “How to Look at Television”—a text all but forgotten by TV scholars today—Adorno warns of the type of appreciation that conflates technical proficiency and narrative complexity with quality while at the same time reminding us that TV, if it is to qualify as “art,” doesn’t necessarily have to pat us on the back.

TV viewers and critics, he claims, “have become shrewder in their demands for perfection of technique and for reliability of information as well as in their desire for ‘services;’ and they have become more convinced of the consumers’ potential power over the producer, no matter whether this power is actually wielded.” This is an all too apt description of the state of Academic Fandom, but Adorno reminds us that getting out of our comfort zone, moving away from being a fan—even an informed fan—is the only way critics can challenge TV’s hold on us and its uses in society. This is a challenge, Adorno claims, “of a moral nature,” and TV scholars would do well to approach what they do in such ethical terms.

Image Credits:

1. AP Photo/Nick Potts. Accessed 11/18/2010

2. AP Photo/Donna McWilliam. Accessed 11/18/10

3. AP Photo/Charles Krupa

Please feel free to comment.

- Gary R. Edgerton, The Columbia History of American Television (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 86 [↩]

- Michelle Hilmes, “The Bad Object: Television in the American Academy,” Cinema Journal 45, No. 1, Fall 2005, 113. [↩]

- Jason Mittell, “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television,” The Velvet Light Trap 58.1 (2006) 38. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/the_velvet_light_trap/v058/58.1mittell.html#bio. Accessed 10/5/2010 [↩]

David,

Hurrah! I have been beating the drum for some years now to legitimize the study of televised sports. It boggles the mind that we (media scholars) continue to pore over shows, franchises and characters that have had ample attention in the literature and we neglect the monstrosity that is TV sports. Thanks for lifting our conversation higher.

Kudos, David, on a thought-provoking essay. You’ve hit upon two tendencies that have long been bees in my bonnet: 1) that sports are neglected; and 2) in a field that celebrates the popular, a handful of series garner the lion’s share of attention. To the latter point, I think that many, in an effort to combat elitism, have simply installed another equally elite form of it in its place. The amount of scholarship on Buffy the Vampire Slayer relative to that on, as you suggest, the Super Bowl, attests to this over-correction.

Thanks for this provocative piece. I completely agree with your call for media scholars to focus more attention on sports, and I think this extends to the classroom (a topic you broach in mentioning the dearth of material on sports in television textbooks). In addition to our own research, we can and should do more to fold sports into our media history, theory, and criticism curricula. For example, I would love to see sports broadcasts incorporated into our screening lists next to the usual suspects by MTM, Lear, et al.

But I do have one question. When you bring up sports as a challenge to scholarship based on “fandom predicated on identity and narrative appreciation,” are you suggesting that we not just broaden our topics of study but that we move beyond these scholarly approaches altogether? If it is the latter, I’m not sure if we need to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I see sports as a rich site of inquiry for both of these strands of media scholarship, and in fact you seem to suggest the same in your discussion of Schilling’s bloody sock. The examination of television through, as you call them, “identity politics,” has always been a cornerstone of critical-cultural media studies, and sport is one of the chief venues in which identity positions are represented, policed, negotiated, and fetishized in media culture. I apologize if I misunderstand your argument, but I wonder if you might say more specifically about what type of sports scholarship you would like to see.

This is a fantastic essay. I think that focusing on televised sports is a possibly MASSIVE field of scholarship. I mean, look at one of the examples: The English Premier League. There are so many households that watch it, every game follows a similar structure, and the dialogue of the commentators are all very basic entry points into a larger discussion. I mean, fan studies would have, literally, a field day looking at how sports fans interact with their sports team. I know that the academy doesn’t like sports, but they probably should start.

A question that I have is does the narrative for TV scholars have to be contained within the realm of the program itself? I think that the interest in TV for me is both in the narrative complexity of the show as well as how it moves outside of the show through the fan’s active defense. As well, as a TV fan, I write about shows both that I like and don’t like. I don’t like writing papers to congratulate myself. I don’t really want to congratulate myself for doing something I would be doing regardless.

This essay was a breath of fresh air, and thank you for bringing some of these issues out into the open. I have myself been confounded by the lack of attention paid to sports broadcasting in TV scholarship. With an industry as global and far-reaching as sports broadcasting is, its exclusion from the academic conversation is mind-boggling to say the least. I find that what has defined TV scholarship thus far to be frustratingly narrow; focusing mostly on scripted fictional shows and/or reality shows that been so heavily produced and craftily edited that they are themselves basically works of fiction. But you have hit in on the head: where are the sports in all of this?

You adroitly address the issue of narrative complexity and that argument situates itself perfectly, as you discuss, in the 2004 World Series campaign of the Boston Red Sox, and in baseball in general. I am a baseball fan, and more specifically a Red Sox fan. But I live in California. However, for the past 5+ years running, I have purchased the MLB Extra Innings package from either Time Warner Cable or DirectTV (depending on where I’ve been living). Regardless of distance and the coastal time difference, from the months of April through October, I am in front of my TV daily to watch the Red Sox games. The accessibility of this TV package allows me to follow in the daily drama of my team, and so often my mood is predicated on how they do. For me, this is the best kind of soap opera there is. The ability to do this, and live in this daily drama, is only possible through the technology of television (and its recent convergence with the internet). TV scholarship is so often devoted to the dramatic, the melodramatic, the soap opera, etc., and each of these elements play themselves out in real time, in every sport. It is no different. Thank you again for this article, and I hope it further discussion.

Thank you for another informative blog. The place else may I

am getting that kind of info written in such a perfect approach?

I have a undertaking that I am simply now running on,

and I have been on the glance out for such information.