The Raw and the Cooking Channel: Men, Food and the Network Brand

Sarah Murray / FLOW Staff

In late May 2010, Scripps Networks Interactive (SNI) launched Cooking Channel, a spin-off of the long-running U.S. cable channel Food Network and replacement for the flatlined Fine Living Network. The channel joins SNI’s family of niche networks – Food Network, HGTV, Travel Channel and the DIY Network – in an attempt to meet what the lifestyle media giant considers an overwhelming consumer demand for food-related programming. Creators behind Cooking Channel have worked to distinguish the network from its sister channels with a carefully constructed brand that focuses on producing cultural television specifically for “food people” who are authentically and passionately “interested in upping their food IQ.”

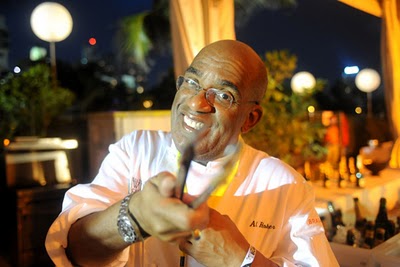

A scan of Cooking Channel’s lineup reveals an inventive yet familiar 24-hour schedule that includes not only the well-established domestic instructional cooking show but also plenty of promised “cultural” programming – shows that detach from the domestic sphere to focus on food history, trivia, and knowledge.1 Despite its distinction as the Cooking Channel, shows like Mo Rocca’s Food(ography), Ted Allen’s Food Detectives, and Al Roker’s My Life in Food work to craft a network focused on food information rather than preparation.2 Strikingly, men are integral to this identity.3 Men and women have long shared hosting duties on national commercial television.4 Yet on Cooking Channel, men alone appear to be leading a shift away from what to do with food and toward what food is. What is the relationship, then, between Cooking Channel’s desire to be the network that dispenses cultural food knowledge and their overwhelming use of men as representatives of the channel?

Integral to Cooking Channel’s network branding has been a collection of 30-second promotional trailers that scatter and loop continuously. Their purpose is to introduce the channel’s cast and provide viewers a flavor of programming, while tying each show to the network’s root identity. These formulaic spots all begin with the Cooking Channel logo and end with a combined visual and voiced-over tag of “Cooking Channel. Stay Hungry.” (The visual brand of the channel aligns with its heavy use of men. The promotional materials’ high aesthetic feel is also subtly masculine – simple, straight lines and a focus on two-tone coloring.) Wedged between the opening and closing tags is a series of quick cuts of the hosts interacting with food, and a voiced-over announcer (usually male) to offer details about the show. These spots function as a surface-level jumping-off point for an examination of how Cooking Channel’s branding objectives are mediated by men.

First, Cooking Channel loops several trailers designed to promote the network as a whole. Running frequently is a spot that highlights five original shows and systematically outlines Cooking Channel’s intended image. The trailer begins with Dolce Vita’s David Rocco saying emphatically, “Italians have this thing with food….” (i.e. mediating a direct link to a different culture) before cutting to Unique Eats’ Danny Meyer detailing the history of the classic shake stand (i.e. food history and trivia). The camera cuts to a wide shot of Australian Bill Granger of Bill’s Holiday standing on a boat in the middle of the ocean saying, “I love great food…and I’m always interested in where it comes from” (i.e. curiosity, passion). A medium close-up of Swedish-Ethiopian Chef Marcus Samuelsson follows, as Samuelsson says, “And that’s why I felt like it was important to tell that story. Food is my vehicle” (i.e. global novelty, food as culture carrier). The spot ends with Food(ography)’s Mo Rocca saying, “Carry extra napkins.” The male voice-over weaves in and out of the trailer, solidifying the message with a hook that explicitly tells us what Cooking Channel is: “A smart new network for today’s food lover…With inspiring chefs…With unique flavors from around the globe…This is Cooking Channel. Stay Hungry.”

Women are entirely absent in the promo detailed above. In other general network trailers, they are largely silenced. In fact, of the few seconds afforded to women in these channel-wide promos, much of that time is reserved for Chef Aida Mollenkamp to utter a high-pitched squeal rather than actual words. These spots present a particular attitude toward food, making a bold statement about who can present information about food in an interesting, relevant way that builds personal development. Seemingly, men can be trusted to lead “food lovers” to passion, knowledge, expertise, and diversity of experience. Women are still available to be enthusiastic supporters in the kitchen.

Cooking Channel has also produced a number of show-specific 30-second spots. The broad, all-inclusive hook that tied together the network promo above – “A smart new network for today’s food lover” – is replaced with a line that summarizes the individual host’s food philosophy. Each spot ends with the narrator confidently asserting what “He” can offer the audience:

Luke Nguyen’s Vietnam: “He’s Luke. And he’s finding new ways to stay authentic. Luke Nguyen’s Vietnam. Tonight at 10.”

Food(ography): “And Mo Rocca doesn’t just touch on it, he digs deep to give you something to really chew on… And he’s always looking for ways to stay engaged.”

Everyday Exotic: “He’s Roger. And he’s always finding new ways to stay unique. Everyday Exotic. Tomorrow at 9:30.”

Fresh Food Fast: “He’s Emeril. And he’s always looking for ways…to stay forward thinking. Fresh Food Fast. Wednesday at 8:30.”

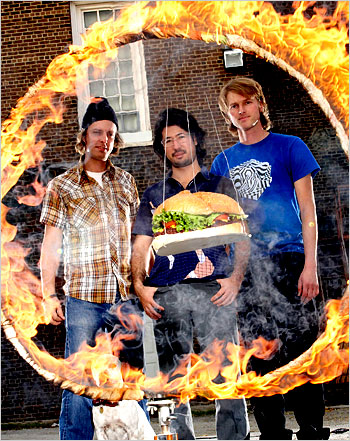

Food Jammers: “They’re artists, inventors, and dudes who can really cook. They’re the Food Jammers. Which means they’re always finding new ways to stay inventive. Food Jammers. Tonight at 10:30.”

Each spot ends with “Cooking Channel. Stay Hungry.” Cooking Channel’s work to be a network that takes food seriously – a network that encourages its viewers to “stay hungry” – is contingent on the men who promise to “dig deep” and deliver new ways to make food authentic, forward, unique, inventive, and engaging. At once, these trailers suggest the notion that “real, authentic culture remains the prerogative of men” and work to solidify Cooking Channel as a legitimizer of food.5

It is perhaps unsurprising that men would begin to take over as food television moved farther from the cooking kitchen. After all, food’s gendered history is drawn down the public/private line, wherein women are charged with the work of home cooking and men are masters of the art of gastronomy (ie: home kitchen/restaurant, cook/chef). Thus on some level, Cooking Channel’s use of male hosts to authorize food’s shift from its deep roots in the domestic sphere to a place among the culturally relevant makes sense. It capitalizes on the long-standing alignment of men with expertise and high culture.6 But it’s not entirely that simple. Cooking Channel’s use of men to facilitate the branding of a particular identity is wrought with interesting tensions. For one, although the network is dominated by men, an ostensible fluidity of gender performances demonstrates that hegemonic masculinity is not necessarily privileged.7 The most straightforward example of the channel’s attempt at “upping food IQs” is Mo Rocca’s Food(ography), a show that focuses on deeper understandings of food (i.e. history of cheese) or food-related concepts (i.e. why do we like hot and spicy?). The segments are narrated by Rocca in campy, deadpan voice-over and organized by visits to the show’s main set – a dining room featuring a long wooden table that Rocca is frequently sprawled atop.

Queer Eye’s Ted Allen hosts the previously mentioned Food Detectives. He begins every episode with an enthusiastic “Welcome to our kitchen laboratory…we’re answering all the questions you have about food with real science!” Cooking Channel’s men deliver food knowledge in a way that paradoxically depends on the traditional notion of the masculine/feminine divide (science lab=masculine), but also defies that line by existing in the cracks of gender performativity. It seems to matter less how much a host strives toward a hegemonically masculine performance, and more that that host is male. Further, shedding light on Cooking Channel’s gender gap is of little value without considering the network’s contingent of men who represent a diverse range of ethnicities, through shows like Luke Nguyen’s Vietnam, Everyday Exotic, and Caribbean Food Made Easy with Levi Roots. Finally, programs like Food(ography) and Food Detectives also complicate matters by revealing in their narratives an incongruity between host and expert. While men are the faces of these shows, episodes often reveal the necessity of a return to the domestic kitchen in order to find women who can unveil the truth of food history with recipes, techniques, and long-held family secrets.

In Cooking Channel’s use of men is a branding strategy that provokes a number of questions about gender, food, and television. As men lead viewers away from how-to cooking and toward food capital, Cooking Channel presumably relies on a male-ness that bolsters the seriousness with which viewers adopt the lifestyle of a “food lover.” Consequently, the network leaves unaddressed women’s changing (or unchanging?) role in how food knowledge is disseminated. Further critical explorations of Cooking Channel‘s gendered discourses are warranted given food television’s current pervasive moment.

Image Credits:

1. The chefs and hosts of Cooking Channel

2. Al Roker gets serious about food’s cultural power on My Life in Food

3. One of Cooking Channel‘s boxy, no-frills logos

4a. Two of Cooking Channel‘s leading men: David Rocco and Bill Granger

4b. Two of Cooking Channel‘s leading men: David Rocco and Bill Granger

5. The three “dudes who can really cook” from Food Jammers

6. Mo Rocca striking a pose during Food(ography)

7. Ted Allen on the set of Food Detectives

Please feel free to comment.

- For a brief history of food programming on U.S. television, see Kathleen Collins’ Flow article, TV Cooking Shows: The Evolution of a Genre. [↩]

- Certainly, food television has been about more than food preparation for a long time. Food Network’s launch in 1993, for example, coincided with a boom in lifestyle programming that forced a gradual shift away from the basics of how-to cooking. See Ashley, Bob, et al. Food and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, 2004; and, although it focuses on British TV, Brunsdon, Charlotte. “Lifestyling Britain: The 8-9 Slot on British Television.” International Journal of Cultural Studies. 6.5 (2003): 5-23. Michael Pollan also offers an easily accessible take on the shift from a cooking kitchen to a consuming kitchen in “Out of the Kitchen, Onto the Couch.” [↩]

- Informally, a review of any given week of Cooking Channel’s schedule of both original airings and re-runs, shows featuring men as the lead outweigh shows featuring women 65%/35%. This doesn’t include assessment of shows with ensemble casts and commercials, although as I suggest in this column, promos featuring men appear to run more frequently. [↩]

- James Beard’s I Love to Eat premiered on NBC in 1946, but women hosted shows with nationwide audiences beginning in 1947. See Collins, Kathleen. Watching What We Eat. New York: Continuum, 2009. [↩]

- Huyssen, Andreas. “Mass Culture as Woman,” in After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986. 47. [↩]

- For a more detailed look at the relationship between high culture/mass culture and masculine/feminine, see Ibid. [↩]

- For more on lifestyle television and contemporary masculinity, see Exposing Lifestyle Television: The Big Reveal. Ed. Gareth Palmer. Burlington: Ashgate, 2008. [↩]

I have no doubt you are correct about this promotion and its male-centric approach. How funny, though, that I have escaped to the Cooking Channel to get away from exactly these types of programs. If you saw my DVR, you would see Giada, Ina, Julia Child (love that she is on Cooking Channel) and my new favorite, Bal Arneson, aka “The Spice Goddess”. The Cooking Channel also features several BBC cooking programs that feature Asian cuisine, a rarity on Food Network since the (regrettable) departure of Ming Tsai.

Food Network is barely represented on my DVR queue because of the trend you describe–a shift to programs hosted by the likes of Guy Fieri that are less about cooking than about contests, documentaries and encyclopedic approaches to food. Though I am not sure where Cooking Channel is going, I agree that the role for men within food programming is worth exploring. As is the slippery use of the term, “chef,” and the prominence of female cooks without formal training (Sandra Lee, Rachel Ray, etc).

Comment copied from moderation queue / improperly marked as spam [ed.]

Charlotte Howell | cehowell6@gmail.com | cehowell.wordpress.com | IP: 24.153.143.125

Great post, Sarah! It’s striking how similar the description and image you use for Food Detectives appear to Alton Brown’s long-running Good Eats on rival/inspiration Food Network. How much of this branding to you see as oppositional to the Food Network? The Cooking Channel may provide an alternative 24-hour food-oriented network that seems almost a reaction to Anthony Bourdain’s infamous flaying of FN. (Of course, Bourdain’s rant bears some gender discussion as well.)

Glad I was told to check out FLOWTV. Very interesting stuff. I learned more about the food / cooking broacasting world than I ever realized existed. I have prided myself on being a closet chef since I was a youngster. After reading this post I plan to broaden my horizons beyond Rachel Ray !

Love Love Love Ted Allen .. thanx Ted …

Thanks for this provocative piece Sarah. I think you’re tapping into a really interesting cultural shift that definitely deserves more exploring. Sounds as though there may also be some interesting discussions related to class and race issues as well. I’m thinking about issues related to authenticity — especially in relation to the travel-oriented programming. Great piece as it stands though!

I definitely love your take on the male dominance within cooking shows. I was struck recently, while watching Masterchef, that there seems to be no need for there to be three(!) men judging the contestants, which seemed rather excessive. More to the point, the show brought Kat Cora on in a really brief appearance – which seemingly (and somehow simultaneously) marginalized her.

Should be interesting to see how gender politics play out on Top Chef: Desserts, but so far it really seems like male dominance in the “professional” kitchen is the order of the day, whereas woman are marginalized into more “domestic” roles (think Martha Stewart) or as curvy hosts of the shows.

Thanks for the great post!

I wish to convey my love for your kind-heartedness for men and women who should have help with the subject. Your real commitment to getting the message all around was rather invaluable and has specifically encouraged somebody like me to arrive at their endeavors. Your new warm and friendly useful information entails a great deal a person like me and somewhat more to my mates. With thanks; from everyone of us.

The issue of gender and television cooking programs is one wrought with tension and, as the Murray article illustrates, it is interesting to examine even promotional material in this regard. I believed the promotional material for ABC’s The Chew would be similarly one-dimensional and gendered. Yet, in analyzing the program’s web-based campaign, including roughly seventy videos that feature the co-hosts imparting valuable kitchen wisdom to viewers (ex. how to cube watermelon), this was not the case.

While not all the co-hosts are featured as equally within these videos (for example, Mario Batali and Daphne Oz are featured in only a handful), the remaining three (Michael Symon, Clinton Kelly and Carla Hall) have roughly the same amount of videos among them. While each of their set of videos have different themes reflecting their different styles or areas of expertise, they are all approached in the same way — similar aesthetics and rhetoric used as to not portray anyone as more superior or knowledgable etc. The Chew’s marketing campaign is effective in introducing viewers to the content of the show and the co-hosts. Yet more importantly, the equal weight given to its hosts appropriately reflects a program, which attempts to bring everyone in the kitchen regardless of gender.