From Cynicism to Sentimentality: The Rise of the Quirky Indie

With the Oscars barely having passed us by, it is worth pausing for a moment to think back on the movies that “made the cut” for the nomination for Best Picture this year. The list – comprised predominantly of releases from the studios’ specialty (or “indie”) film divisions – consisted of many of the usual types of films deemed Oscar-worthy1. There was the star-driven conspiracy thriller (see The Insider, Erin Brockovich) and the historical romance/literary adaptation (see The English Patient, Shakespeare in Love). In addition, there were two nominees from the omnipresent “auteur-driven indie” category (see the filmography of the Coen brothers and Paul Thomas Anderson).

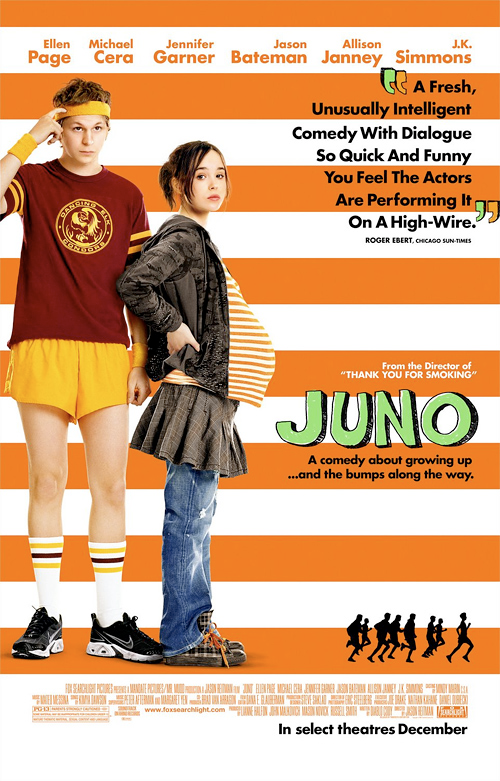

Then there was the “little movie that could” entry, Juno (think My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Little Miss Sunshine). This dramedy about teen pregnancy was perceived by many in the popular press as the “wild card” in this year’s Best Picture race. Also surprising to many has been its runaway box office appeal. With more than $125 million grossed at the U.S. box office to date, Juno has earned more than double the sum of its nearest Oscar competitor, No Country for Old Men2.

Juno’s box office performance seems particularly remarkable when its grosses are compared to those of several other recent high-profile releases. For example, the male- targeted Rambo topped out at $40 million, the female-skewing 27 Dresses hit a ceiling at $71 million, the baby boomer “sleeper hit” The Bucket List stalled at $82 million, and the most recent Tyler Perry release (Why Did I Get Married?) left theaters with just $55 million. Even the over-hyped youth-oriented Cloverfield – which has yet to reach $80 million in North America – is fading fast.

A discussion of these numbers raises the question: who is seeing Juno and why? While this query cannot be answered without further empirically-based audience research, it does point to a more speculative question, which I would like to probe here: Namely, what interests or desires might this film have tapped into in terms of contemporary American culture – and how unique is it in doing this?

Certainly part of Juno’s appeal stems from its clever dialogue and its iconoclastic, strong-willed lead female character. And of course, the high degree of publicity surrounding the film – especially the widely circulated “stripper-turned-screenwriter” narrative told and re-told about scribe Diablo Cody – has been a useful marketing angle. The presence of cult teen star Michael Cera of Arrested Development and Superbad fame doesn’t hurt either. But I think that the film’s buzz is not limited to just these factors. Rather, I believe one can better gauge Juno’s longevity in theaters (which, as of this writing, is going on three months) by considering the relationship between the film’s tone and its narrative trajectory.

The film starts with a first trimester Juno, cynical yet idealistic. The early part of the movie is filled with snappy one-liners and witty repartee. However, as the seasons wear on and Juno becomes more pregnant – and more involved in emotional complications with the adoptive parents – much of the fun banter fades, as does Juno’s idealism. She re-adjusts her expectations, re-thinks her relationships, and becomes less guarded, less jaded. By having her ideals challenged, she actually becomes more hopeful about life’s possibilities and her own future. In other words, we witness both the character of Juno – and the film itself – become more sincere.

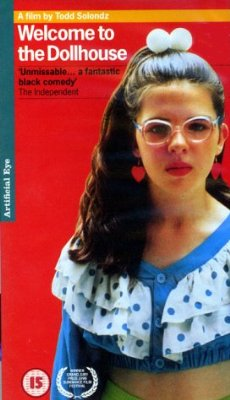

This sincerity seems counter to the tone and substance of the majority of the edgy ‘90s-era indie films. One need look no further than the aforementioned Oscar nominees, There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men – both products of filmmakers whose careers flourished during the post-Disney Miramax age (1993 on). Thinking back to the tales told about other notable teenage characters in indie films during the ‘90s and early 2000s is equally suggestive. Just a few examples include Dawn Wiener in Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995), Dede Truitt in The Opposite of Sex (1998) and Enid and Rebecca in Ghost World (2001). As with the edgy indies of Anderson and the Coens, the world these characters inhabit is much darker, their outlook much bleaker (not Bleeker).

This comparison offers up two possibilities for why Juno has taken off: First, the ‘90s-era edgy indies speak to – and for – a very different generation of viewers, raised on different media and a distinct socio-political climate. Perhaps my response to the “optimism-in-spite-of-adversity” outlook of Juno derives from my presently-obsessive viewing of political coverage which trumpets “change,” “hope” and “inspiration.” Or perhaps it comes from witnessing several of my students routinely wearing Barack Obama stickers, t-shirts and buttons. But I am inclined to think that some of Juno’s appeal springs from the coming-of-age of a new generation along with a more widespread desire to just stop with the cynicism. Perhaps Juno the film and Juno the character speak to, about, and for youth in a way that many other recent popular culture artifacts have not.

The second possibility for the film’s widespread appeal more directly connects to industrial factors. Juno was distributed in the U.S. by Fox Searchlight, the specialty division of Fox/News Corp. In fact, it has become Searchlight’s highest-grossing release in the company’s ten-plus year history. For a company that has released such high-profile films domestically as Bend It Like Beckham, Garden State, Napoleon Dynamite, Little Miss Sunshine and The Darjeeling Limited, this is an impressive accomplishment.

I mention these titles – and this company – not simply as background information, but to suggest that there are striking ties between many of these films and Juno. Most notably, the latter three titles are, unlike the films of Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Smith, less edgy and more quirky. This “cinema of quirkiness,” which is becoming increasingly noticeable, is less likely to present sex, violence and coarse language than it is to depict off-kilter but well-intentioned characters engaged in offbeat activities. In these films – of which Juno is clearly one – characters may screw up and get themselves into unbelievable and often unfortunate situations. But in spite of their missteps, they appeal to audience sympathies because in the end they mean well and they are kind. Not unlike Juno’s pregnancy, their momentary slips permit them an escape and a return to who they really are: youthful idealists3.

Certainly there were precedents for this in the ‘90s. (Wes Anderson’s entire body of work comes to mind here). However, in the last few years, this type of film has become more prominent, not in the least because Fox Searchlight executives appear to have identified it as a lucrative niche with a viable audience. It seems highly likely that, given the immense financial success of Juno, and the degree to which it seems to tap into this particular cultural and political moment, we can anticipate more such characters to appear in theaters – and possibly the Oval Office – in the near future.

Image Credits:

1. Expecting a limited release?

2. Screenwriter Diablo Cody and Juno star Ellen Page

3. Youth, ‘90s Indie-style

4. A Return to Idealism?

Please feel free to comment.

- In the U.S., Warner Bros. released Michael Clayton; the indie releases come from Focus Features (Atonement), Fox Searchlight (Juno), and via joint venture of Paramount Vantage/Miramax–both There Will Be Blood and No Country for Old Men [↩]

- According to Variety.com, box office grosses for the Oscar nominees as of the week of February 18th were: $32 million for There Will be Blood, $47 million for Michael Clayton, $48 million for Atonement, $60 million for No Country for Old Men, and $125 million for Juno. [↩]

- Thanks to Steve Perren for his input on this point. [↩]

Great piece. Your column has helped me unpack “Juno” and place the film in a broader context. First of all, I want to like this film. My biggest issue with the film is the fact that she carries the baby to full term. When “Juno” is placed in the “full-term pregnancy” canon alongside “Waitress” and “Knocked Up” (all released in 2007) I almost have to go out and see the gritty, depressing, even pessimistic “4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days.” I understand audiences wanting to see something uplifting and sentimental on the big screen – but why oh why does Juno have to bear the burden of the film’s sentimentalism. The fact that Juno’s pregnancy correlates with the film’s (growing) idealism makes me wonder if there is not something repressive and constraining underneath that fuzzy warm feeling at the end.

I agree wholeheartedly with K’s suggestion that there might be something “repressive and constraining” at the end of “Juno.” Patriarchy, heteronormativity, privileging male autonomy and freedom by limiting the sphere of “children” to women — all these ideologies and more can be found surging throughout the film. No matter how many ultra-trendy pop culture references or Moldy Peaches songs get inserted into this narrative, it can’t hide its real feelings about essentialized gender differences or idealization of traditional families (carefully cloaked, of course, in images of non-traditional families). I appreciate this columnn’s efforts to place the film into contemporary discourses of “optimism,” but I wonder how much has really changed in terms of the underlying ideology. I’d love to see a version of “Juno” where she has a wonderful first sexual experience and then just goes on with her life — rather than this one, in which her sexual autonomy immediately becomes problematized. Despite all of this, though, it’s great to see a column here on Flow trying to unpack this cultural moment.

Alisa, I’m not sure about the generational argument, since many of the same people were the audience for the 90s edgy films and the more recent quirky-sincere films. I also think Juno could be considered edgy with its talk of pork swords and its casual take on adolescent sexuality, even though it turns sweet by the end, which I would guess is important for its positive word-of-mouth. Little Miss Sunshine is edgy in some ways too, e.g., the foul-mouthed grandpa, the suicidal gay uncle. And many of these more sincere films do have their share of sex and naughty words. I agree completely, though, that their tone is different from the bleak indies you mention. The straight-up emotional appeal of the quirky indie would seem pretty important for cross-over potential. Darjeeling was obviously going for this too.

Another explanation for Juno’s success must be its good fortune in being released around the same time as other comedies of unplanned reproduction, making it part of a trend. It especially benefited from coming a few months after Knocked Up, making it the female antidote to Apatow even though it was probably not intended that way. At the very least, it gave reviewers a good hook and shaped the way people would talk about the movie.

I do find your Fox Searchlight points here especially perceptive. Their strategy of crafting “sleepers” seems really smart, tapping into consumers’ interest in alternative culture that isn’t too threatening. In this instance, the mainstream really has become its own competition. And the media seems to buy their line that Juno is a “little movie that could” even though that was Searchlight’s marketing strategy from the start rather than some kind of grassroots phenomenon. We also shouldn’t discount the power of cross-promotion with the hit soundtrack album, and the brilliant campaign on the web with all those clever videos of the cast being so spontaneous.

Pingback: The Chutry Experiment » Monday Links

Warning: I’m going to come across as a cranky “kids these days” counterculture crusty in this post.

It’s interesting to me that despite the fact that Juno’s favorite three rock artists are the Stooges, Patti Smith, and the Runaways, they are nowhere on the soundtrack. The Melvins also get a mention, but the film silences them as well.

Clearly, the film tips its hat to these producers of punk/alternative/indie culture in order to up its cultural capital, but their angry, cynical, noisy–or should I say “edgy?”–sounds would disrupt its sentimental tone.

What would become of the narrative if the film were to include these angry sounds? Why mention the Stooges, the Runaways, Patti Smith, and the Melvins at all?

What’s also interesting to me is the privileging of a kind of deadpan naivete as performed by Ellen Page and Michael Cera as well as the Moldy Peaches. A certain kind of toes-turned-in, amateurish, faux-naif performance has been characteristic of indie rock since at least Jonathan Richman, but it was often accompanied by anger and nihilism. I’m thinking especially of Sonic Youth. They might have acted like lovable moppets, but they cranked out a furious sound.

I think this performance of naivete read as sincerity, as playing music for love rather than money. Since the 1980s, it seems that indie culture has gradually shaved away the anger while keeping the sincerity. I would give my left arm for a copy of an MTV report on the Warp tour of 1994, in which No Doubt, amongst other bands, declared “the end of angst” in response to the prevailing emotional style of Nirvana and other alternative rock bands of the early 1990s.

Juno reflects or represents the indie culture of Polyphonic Spree, Mates of State, Bright Eyes, Modest Mouse, Feist, the Shins–that is to say, bands that, similar to Moldy Peaches, perform a naive, quirky, sincerity.

To echo K, I find all this wistfulness oppressive and constraining.

Thanks all of your insightful comments. Clearly there is much more than the 1000 words provided to write about this film.

In terms of Juno’s generational appeal (or lack thereof), I remain uncertain. My preliminary assessments were based on a polling of my undergrads to see which of the Oscar movies they had seen. Obviously this is not a representative sample, but more had seen Juno than any other film nominated for Best Picture. Of course, seeing it is not the same as liking it, and there is now more to be written about Juno, post-Oscars, as the backlash against it (and the screenwriter) is becoming even more noticeable.

My interest in writing this piece

was mainly in assessing its tone/sensibility and considering how that might factor into its wide appeal. It is worth underscoring that by no means do I endorse or support this tone/sensibility. I am the first to acknowledge there is much that is problematic about the movie, and I am glad to see that it is provoking such a response. There is certainly much to debate!

“Alisa, I’m not sure about the generational argument, since many of the same people were the audience for the 90s edgy films and the more recent quirky-sincere films.”

Todd Solondz’s early films weren’t earning $125m because they weren’t as popular as Juno; surely this is because they weren’t aimed at ‘average’ audiences – and deliberately targeting teens. I would argue that Juno is a teen movie dressed up in the generic characteristics of those 90s indie movies.

The film is consumed via a discourse of ‘indie’ because a) that’s how it was sold, b) it shares enough characteristics with the indie aesthetic and c) it addresses a socially ‘controversial’ subject. However, as has been mentioned these discourses are belied by its production context and the entire aesthetic.

For what it’s worth I left the cinema feeling that the entire film didn’t know what it was. Reitman’s direction was in a comedy register – as was the first 20 minutes of the script. But the ‘sincere’ turn wasn’t accompanied by a change in style. I was left feeling that I was watching an unfunny comedy.

I think Juno, Little Miss Sunshine, Garden State, etc. are typical of Hollywood cinema appropriating extra-industrial aesthetic tics to increase product differentiation (a la Adorno et al).

Ultimately they’re still in the business of selling utopias, not ennui and self-examination. Which is fine – I like utopias. But I think these type of films may have pushed the Hal Hartleys/Tod Solondzs/etc out of the art cinemas that once showed them – at least in London and the UK. And I think that’s the shame.

Matt’s Adorno-tinged reading sounds about right to me. I remember being surprised at how sentimental Juno was when I saw it in theaters just a week or so after it was widely released.

But I also began to notice around the time of the Oscars that the rhetoric of the ads changed, placing emphasis precisely on those sentiments. Less quirk. More hugs. That being said, I *prefer* those extra-industrial aesthetic tics to summer blockbusters, so looking at how those preferences manifest themselves with films like Juno, Little Miss Sunshine, etc, might be worth trying.

I’ve never been a fan of Todd Solondz, but I think Matt is also right to lament what appears to be the marginalization of people like Hartley and Solondz from the major art house screens where they used to screen.

I’m curious: if Feist, Modest Mouse, and Polyphonic Spree are the music version of wistful, then what, besides Juno, is the filmic equivalent?

Does Junebug work?

I guess I’m curious if we can agree on films in this category — the article and a number of posts gesture towards this emerging genre, but besides Little Miss Sunshine, I can’t think of many of their supposed quirky, whimsical brethren.

I agree with Chuck. It’s important to separate the idea of a “little movie that could” — which are almost always films that are distributed by the “edgy” divisions of major studios/media conglomerates — from true indie films. More people see these movies, more people talk about them, they are generally nominated for more awards…so they migrate into the territory of cultural phenomenon. (Building on what Annie said about music — would we be asking what Feist says about our culture if she wasn’t in the i-pod commercials?)

I think what we like about dissecting these movies-that-could is the fact that their “unexpected” popularity somewhat subverts the feeling among sophisticated viewers (angsty youth included in that category) that Hollywood is spoon-feeding us TOTAL CRAP. It’s nice when Hollywood’s step-brother serves us an edible entree on a plate — and even better when it’s comfort food.

Having read this piece, in conjunction to “The 2008 Academy Awards…and the Evil Just Outside the Frame,” in the same issue of FLOW, I know see “Juno” as not simply an exception to the “doom and gloom” films treated in the former essay, but an antiphonal balancing act — the evil might be out there in the other films, but in these quirky good-natured films with redemptive endings, the good is right there inside.

I’d maybe place Michel Gondy in the whimsical (but no unknown indie) form, especially The Science of Sleep but also Be Kind Rewind more recently.

On whimsy, Charlie Brooker, a satirical columnist in the UK, wrote about this type of aesthetic in adverts some time ago: http://www.guardian.co.uk/comm.....dvertising

“Right now, there’s a rash of commercials which combine “twee” with “patronising” – “tweetronising” if you like, although that’s quite tweetronising in itself. You can spot a tweetronising commercial a mile off – it’ll have a modern folk music backing track, a cast of non-threatening urban hippy replicants, and a drowsy hello-birds-hello-sky overall attitude that makes you want to chase it down an alleyway and kick it until the police arrive.”

For consideration:

– http://youtube.com/watch?v=F6f.....re=related

– http://youtube.com/watch?v=1cO.....re=related

– http://youtube.com/watch?v=BhHwlIVeflw

Spurious perhaps but it interested me.

Juno’s success at the box office could be the result of the messages it sends about teen pregnancy. Most girls who find themselves in similar situations as Juno might consider abortion more seriously, but the movie opts for alternatives to teen pregnancy which helps appeal to wider audiences. The fact that Juno opts for adoption instead of abortion shows the movie was aiming to show a rather unexplored element of teen pregnancy in movies. The adoption element appeals to more conservative audiences who take a pro-life stance. It would seem that the target audience for the film would be primarily teenagers, but the film offers adult perspectives on teen pregnancy as portrayed by Juno’s parents. The film features Juno’s supportive parents who guide her through pregnancy and defend her when society looks down on Juno’s predicament. This helps the movie attract older audiences, specifically parents with teenagers, as the film addresses teen pregnancy from both the teen and parent perspectives.

The main problem with Juno’s depiction of teen pregnancy is that it presents one-sided commentary on abortion to its audience mostly composed of teenagers. I do not believe that it had a consciously pro-life agenda but through its portrayal of Juno’s pregnancy, it indirectly presents an anti-choice depiction of teenage pregnancy. The problem with the movie is that it never presents abortion as a viable option despite Juno not wanting to keep the baby. Although Juno visits the abortion clinic, she never truly considers having an abortion. Going to the clinic presents abortion as a legal option for her, but not as a moral option. This is just a message that comes with the story that is told. Many people believe that the movie presents a direct aversion to abortion. However, I do not believe the message of the movie is that abortion is morally wrong. The movie would not be the same if Juno sincerely considered obtaining an abortion. If she did the movie would lose sight of its message of learning and growth through life experience. Nonetheless, without real consideration for getting an abortion, the movie presents an anti-abortion overtone.

I think that the character of Juno is a major part of the draw to the film. The film itself is not just quirky, so it the title character. Juno McGuff is painfully hip, indie, and quirky. She has an overly witty response to everything, and in those responses, usually throws a bit of pop culture irony in along with her two cents. Despite her being unrealistically hip and clever, she is a strong female character and in some ways could e viewed as a good role model. Sure, she’s knocked up, uses foul language, and burps unapologetically, but she is a confidant young woman who is brave in the face of difficulties. Juno decides to keep the baby(“and give it someone who like, totally needs it”), which s the tougher of the two roads, and decides she can do it on her own, without Bleeker. While some reader of this article said that the movie is anti-abortion, I disagree. This film explores one girl’s choice to take the more difficult path and put her baby up for adoption.

The film includes another strong female character-Jennifer Garner’s character. She also chooses to undergo a difficult task (raising a child) alone, without her husband. She chooses to make him leave and go at it alone. This is a strong message to teenagers that women do not need to be codependent, and you can be hip and cool and still be a strong woman. Juno is not feminine, but she is a feminist, while Jennifer Garner’s character appears to be both.

Pingback: Kann »quirky« Indie politisch sein? Eine Frage anlässlich Miranda Julys Interviewbuch »Es findet dich« « a c h t m i l l i a r d e n . c o m

Thanks for finally writing about >From Cynicism to Sentimentality: The Rise of the Quirky Indie

| Flow <Liked it!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about From Cynicism to Sentimentality: The Rise of the Quirky Indie.

Regards

What’s up to all, how is everything, I think every one is

getting more from this website, and your views are fastidious in favor of new visitors.