Watchin’ the Noggin: For-Profit/Non-Profit Co-ventures and Children’s Television

I heartily support the fight for further federal funding of PBS. Still, some arguments for supporting public broadcasting have grown rather tatty. Among these is the contention that PBS provides programming for young children that is exceptional in terms of its content, context and quality—that cannot be found elsewhere in the otherwise commercially adulterated television landscape.

Since our television household has found the Noggin channel, this argument no longer holds. It must be admitted that we discovered Noggin in part because we are comfortably middle-class, with the means to afford direct broadcast satellite (DBS) programming. For many who cannot afford DBS or cable, PBS children’s programming remains a truly exceptional, quality bit of broadcast programming. But for the vast majority of U.S. households who subscribe to cable or satellite, there is a growing array of innovative children’s fare that throws into question traditionalist assumptions regarding PBS as the sole preserve for quality, noncommercial children’s programming.

[youtube]http://youtube.com/watch?v=KJlFFQpnb5g[/youtube]

As a direct confrontation to PBS claims to exclusivity in quality non-commercial programming for preschoolers, MTV Networks—as part of Nickelodeon—and the non-profit Sesame Workshop (a 50% shareholder) launched the Noggin channel in 1999. In contrast to PBS Kids Television, which is increasingly marked by 15 and 30 second corporate underwriting spots—that bear a marked resemblance to more conventional ads—Noggin has been completely free of such underwriting spots, and virtually free of sponsor logos, announcements and advertisements. In fact, Noggin is the only “commercial-free” U.S. television channel programmed for preschoolers twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, and airs some of the most critically acclaimed and popular television programming for young children, including “Dora The Explorer,” “Wonder Pets,” “LazyTown,” and “Jack’s Big Music Show.” Noggin’s corporate parent, Nickelodeon Television, currently distributes virtually all of the top ten rated programs for kids ages 2-5. And while Noggin’s reach is currently a smaller share of cable and DBS households compared to the Disney Channel and ABC Family, the decade-long dominance of Nickelodeon in children’s cable and the innovation and rapid growth of Noggin, which claims “it’s like Preschool on TV,” make it a channel worth watching.

The past decade has seen the volume of preschool children’s cable programming explode—to literally hundreds of hours of creative programming offered weekly across a variety of outlets. Beautifully crafted, educationally vetted, multi-cultural and arts-centered programming from around the globe (e.g. Canada, Iceland, France and the UK) is increasingly in evidence. Why? In part, because the potentials for branding and tapping into a younger and younger consumer population have enticed producers and networks to pay more attention to children. As one independent production company president puts it, “It’s now ‘all kids all the time.’”

Operating as an “entry point” for toddlers and preschoolers to the Nickelodeon brand, Noggin has emphasized the channel’s commercial-free environment while rolling out a multiplatform content distribution strategy. This includes the multi-purposing and cross-promotion of Noggin programming and characters across the Nickelodeon network, preschool video on demand, DVD distributions, and sophisticated interactive websites, as well as original television series, such as “Jack’s Big Music Show”—a program that one excited Nickelodeon executive praised as “something we’ve wanted to make for years . . .it’s like TRL for preschoolers.”

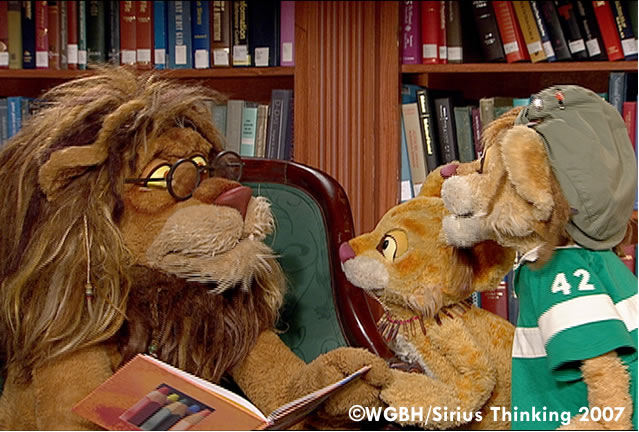

The history of Noggin, and much of preschool television today, reveals that for-profit/non-profit production co-ventures have become a dominant force in the design and structure of young children’s TV. As mentioned earlier, Noggin began as a co-venture of the for-profit MTV Networks and the non-profit Sesame Workshop (In 2002, Sesame Workshop sold its interest in Noggin to Nickelodeon.). A primary Noggin rival, PBS Kids Sprout, begun in 2005 and airing limited advertisements, is a joint venture of Comcast, PBS, and programmers HIT Entertainment and Sesame Workshop. Likewise, many of the most popular children’s shows are produced by for-profit/non-profit collaborations, such as “Dragon Tales”, produced by Sesame Workshop and Columbia Tri-Star Television, “Reading Rainbow,” produced by public television’s WNED and Lancit Media, and “Between the Lions,” produced by station WGBH and the Serius Corporation. And of course, the CPB (Corporation for Public Broadcasting), charged by Congressional mandate with furthering noncommercial and cultural programming, regularly funds such non-profit/for-profit ventures.

In this environment, where global co-ventures enable the production of quality children’s television, and where such non-profit/for-profit models are the norm, it is understandable that the Noggin channel argued before the FCC (in 1998) that regulators should formally recognize the preschool channel as a “noncommercial educational programmer” deserving reserved DBS channel capacities. In their legal brief, Noggin pointed to the “irreconcilable anomalies” created by FCC decision-making defining what is “commercial” and “noncommercial” as well as “for-profit” and “non-profit.” Although Noggin eventually decided to withdraw the petition, their appeal again focused attention on the ways in which such definitions are constantly in flux.

Certainly, the FCC definition of the “non-profit” entity has been selective, dynamic and contradictory. And children’s television, its structure and markets did not simply appear or self-form, but were, and are, constituted and restricted by complex and contradictory regulatory discourses (including those of the FCC) freighted with huge political and economic stakes.

As Tom Streeter has reminded Flow readers (Volume 2, Issue 8), the institutional and cultural arrangements specified in the term “commercial” are not self-evident, but should invite our scrutiny, particularly in a critique of the ways that television’s advertising structure provides an unsatisfying address of a full range of human and citizen desires. Insightful respondents to Streeter’s query, “What is Commercialism?” observed that progressives must consider “the intellectual and political costs of positioning the commercial in opposition to the public”, and that “idealist efforts to separate public service from commercialism inevitably fail,” or at least have within the U.S. context.

On the other hand, preschool children’s television—too seldom studied by television scholars from the humanities —offers hybrid production/distribution models which cast the commercial/noncommercial binary into relief, has reinvigorated independent production (in admittedly limited ways), and proffers some progressive television fare. After watching Noggin and PBS Kids Sprout for a significant length of time, I’m simultaneously troubled by the sophisticated efforts to position the very young as standardized consumers and excited to see how non-profit entrepreneurism joined to for-profit enterprises has re-energized and improved the preschool children’s television landscape.

Might such hybrid models find further purchase and progressive potentials in media sectors outside the sphere of preschool television? Perhaps in web environments? This is a discussion that I’m hopeful Flow can facilitate. At first glance, this seems less than likely in television, but prominent non-profit leaders, including Gary Knell, President and CEO of Sesame Workshop, have expressed enthusiasm for extending for-profit/non-profit collaborative approaches to other TV programming blocks created primarily for tweens and older children.

Alongside the important progressive calls for new public commons, non-profit entrepreneurism and industry restructuring made so eloquently in Flow, the robust and creative hybrid business models prominent in preschool television should prompt our reconsideration of the economic and structural concepts assumed in understandings of U.S. “commercial” television. Practically, they provide a glimpse at how alternative production and distribution collaborations might address, however inconsistently, a greater range of human needs and desires.

Image Credits:

1. Noggin Logo

2. Noggin YouTube Video

3. LazyTown Cast

4. Jack’s Big Music Show

5. Between the Lions

6. Sesame Street On-Line

Notes

1. Angela Paradise. “No Longer “Just a Word” From Your Sponsor: The Increasing Presence (and Power) of Corporate Sponsorship on PBS Kids Television.” Kaleidoscope, 3 (Fall 2004): 22-42. In recent months Noggin has expanded its programming window (from 12 hours) to become a fully 24-hour channel. It has also begun to air infrequent sponsor “billboards” a few times daily, as well as a limited number of promotionals for “family friendly” shows carried on other Nickelodeon channels.

2. R. Thomas Umstead. “How Nick Expects to Maintain Edge in Preschool TV.” Multichannel News, 11 July 2005, 1.

3. Gloria Goodale. “Kids’ TV Builds a Better Foundation,” Christian Science Monitor

16 January 2004.

4. This is not to ignore the excellent Nickelodeon Nation (edited by Heather Hendershot), or important scholarship by Norma Pecora, Ellen Seiter, Sarah Banet-Weiser, and others. Still, much of existing humanities research focuses on television and popular culture connected with older children rather than preschoolers.

Please feel free to comment.

Interesting column, Steve! While I’ll agree the line between for-profit/non-profit children’s television is increasingly blurred, particularly when examined from the vantage point of on-air programming, I have to say that the fact that the line exists at all is meaningful and has–in my view–directly translated into the unique ways preschool programming has developed in both arenas. Each defines itself in relation to the other, distinguishes itself by drawing contrasts with the other, and transforms itself–in part–by emulating the other. They each make the other better. I don’t think that would have happened without the dichotomy, however false it might be in practice, between the non-profit and for-profit models. So while I’m not against joint ventures, I think there’s great utility in that which distinguishes one from the other.

Good points, Steve; any fully developed program of media critique worth it’s salt needs to address these kinds of hybrids, and in a way that eschews any kind of simplistic “pure”/”contaminated” continuum for understanding the relations between various structures of cultural production.

But there’s always a politics there, even in something as innocent-seeming as Noggin. Nickelodeon has always sold ads, but early on a key to its (and I think Noggin’s) success was that offering these channels is a selling point for cable companies, and they’re a selling point because people want something different from the norm for their kids. Part of what makes these hybrids successful, in other words, is a widely shared political sentiment that straightforward ad-supported TV does not offer a nurturing media environment for kids. That’s not really a “market” need; that’s a political need. So, whether we’re talking PBS or Noggin, in each case, part of their conditions of possibility is a certain politics.

There’s good reason to be excited about (or at least interested in) the huge amount of pre-school programming now available. But it is also disconcerting how children’s TV has been infantilized in the past 10 years!

Not withstanding the huge money to be made from tween girls (Hannah Montana, and all that jazz) the most highly coveted demographic as far as the networks are concerned is still 8-11 year old boys (programmers used to claim to target 2-11 year olds, but 8-11 was the real target), because that’s where the biggest toy/candy/game money is. But the actual amount of TV for pre-schoolers now seems to far exceed that for the older kids.

The reasons are many, including responses to the Children’s Television Act of 1990 and the multi-channel, non-network explosion. Sesame Street made “multicultural” synonymous with “educational” (as per Rob Morrow’s book), and now “pre-school TV” is also synonymous with “educational.” Even Sesame Street is now for younger children (hence the creation of baby-talking-Elmo) than it was 40 years ago. The new DVD set of early episodes includes a warning that it is not suitable for young children!