Truth and Beauty

Medical Visuals

Over the past decade I have become a most reluctant television star. The camera, as they say, is drawn to me. I only wish I could say that I’ve enjoyed the attention. If you’ve seen my work, you may be surprised to know that I’m actually extremely shy, and still uncomfortable in front of a camera. In fact, judging by the latest round of auditions for American Idol, I’ve come to think that I may be the last surviving American who can imagine living a full life without once appearing on television. And yet it seems to be my destiny to be hounded by people who will go to any lengths — sparing no expense — to see me appear on their TV screens.

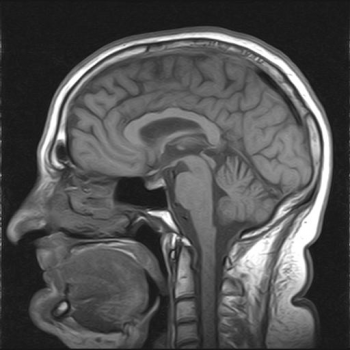

Perhaps you’ve seen my work. I don’t like to boast, but I’ve appeared on TV screens from coast to coast, and I’ve been responsible for some truly memorable on-screen moments. It all began with the MRI scan of my lower abdomen in the mid-’90s — an immature work, I’ll admit, but it was early in my career. In fact, I hadn’t really pursued a career at all; like Lana Turner, I was plucked from obscurity by an eagle-eyed talent scout who spotted me slumped on a plastic chair in a San Francisco emergency room. How was I to guess that one day I would be recognized as the most accomplished medical imaging performer of my generation?

I gained confidence slowly — a CT scan of my skull, a couple chest X-rays, a few more casual MRIs. Sure, I was flattered when doctors and technicians praised these early efforts — who wouldn’t be? But I was something of a dilettante, a dabbler in the world of medical imaging. I didn’t really begin to sense my gift until my first encounter with nuclear medical imaging, when I was asked to swallow a “contrast media.” I enjoyed the vaguely Videodrome-esque possibilities in being allowed to eat the media, but quickly learned that barium and radioactive isotopes are not my medium. Still, it wasn’t long until the cameras were inside my body, instead of hovering around me, and I had discovered my calling. In the past ten years my internal organs have logged more screen time than Dr. Phil.

I don’t know what the object of television studies is these days, but my experience with the profession of medical imaging has brought me into contact with an entire world of digital video technology and imagery that is barely mentioned in the literature of television and media studies. Of course, this apparently invisible screen culture hides in plain sight, where it is taken for granted by millions upon millions of people who encounter it every day. Perhaps it’s time to focus a bit more of our attention on the technology, industry, and visualization strategies of medical imaging.

The NBC television network is the most visible face of General Electric, and, like all television networks, its principal task is to create wealth for the company by making and circulating images to a public with an apparently insatiable appetite for images. But NBC is not the only business in the GE corporate empire that trades in images, nor is it even the most valuable. The GE Healthcare division generates twice the annual revenue of NBC, largely by facilitating the production of images that circulate only within the halls and computer networks of the health care industry, where GE is the industry leader in diagnostic medical imaging.

Inside the body, on your TV

Medical imaging doesn’t hold the glamour of network TV, but its images are vastly more profitable. Since many of these technologies employ proprietary high-tech hardware and software under exclusive patent to GE, the images carry a hefty price tag even though they have no value in an economy of images recognized by the general public. Instead, images made by scanning and fluoroscopic technologies have a singular, functional value for medical practitioners. When interpreted by a trained specialist, they serve as evidence in an investigation; their value increases along with their proven accuracy. The expense of creating and interpreting these images, while contributing to the skyrocketing cost of health care, makes this a lucrative business for GE, which hopes to maintain its dominance in an industry that appears to be poised for limitless growth, particularly considering the future health care needs of aging, relatively affluent populations.

A recent television commercial in GE’s “imagination at work” campaign portrays GE medical imaging technology not only as one of the company’s many innovative products, but also as an essential contribution to the history of western civilization. The commercial takes just thirty seconds to present a sweeping history of human techniques for making images. The rapidly-edited sequence mixes images of instantly recognizable icons with the technologies used to record them: paintings from a prehistoric cave and an ancient Egyptian tomb, a Renaissance portrait, an image produced by a camera obscura, galloping horses frozen in stride by Edweard Muybridge, an early motion picture camera and the Edison company’s famous filmed “Kiss,” an x-ray of a human hand, a shot of the Earth as seen from the Moon’s surface, ultra-slow-motion footage of a hummingbird in flight, time-lapse footage of a flower in bloom, and a distant galaxy revealed by the Hubble space telescope.

As the images cascade, a narrator makes the case for GE: “To the list of the most extraordinary images ever captured, GE humbly submits … the beating human heart.” The screen fills with a startling, lovely image: a living human heart isolated against a black background, rendered in real-time as a three-dimensional image. Unlike an x-ray or a conventional MRI, this scanned image doesn’t require a leap of imagination or a consultation with a specialist to be legible to the untrained eye; it has the precision and clarity of a motion picture, but also an undeniable beauty – a hint of poetic hyperrealism in the emotionally and symbolically resonant image of a beating heart.

Science fiction has promised a chance to peer inside the human body without the need to penetrate flesh, and in this advertisement GE fulfils the promise. In the commercial for GE imaging technology, the physical characteristics of the body — the flesh and bone that are seen as obstacles to diagnosis and treatment — disappear before the penetrating gaze of GE technology. By transforming the body into an image, technology facilitates treatment. What’s striking about the GE commercial, however, is not the instrumental argument in favor of imaging technologies, but that fact that GE makes an essentially aesthetic claim for its new technology: GE has transformed a real human heart into a beautiful image. The question is: why? Why promote diagnostic medical technology by insisting that beauty is truth?

Image Credits:

2. Inside the body, on your TV

Please feel free to comment.

Innards and aesthetics

Thanks, Chris, you’ve given me an entirely new perspective on the many MRIs, CTs, and Xrays I’ve had over the years. I always had this fantasy that my images would be used as teaching tools on day because of the uniqueness of my case, but it seems that I not only don’t have copyright over images of my innards, but I don’t even get notified if/when they’re reprinted or broadcast!

I find myself wondering whether there’s a connection between the aestheticization you identify in the GE ad and the use of ‘gross-out’ innards imagaery in shows like CSI. House in an interesting text in this regard, because blurring the line between medical imagery and televisual imagery seems to be the main way that they try to make the show stand out visually.

i had no idea that the advances of medical imaging were going to be like that. I suppose it saves the doctors alot of time with the diagnoses, but at the same time, technology will tske another step forward into the future. Medical imaging is a visual storyteller, that let’s the doctors and patients know what is wrong with them, and where exactly the problem is located. but medical imaging is far from being an visual art form (even though it’s cool to look at).