Reflections on Katrina in Brazil

I think I know where I am. To my university, I am in the Amazon, land of myth and enchanted Edens, in the words of Candace Slater. To Brazilians, I am in Manaus, home to the eighth largest city nationally and the largest free trade zone in the Americas. To residents, called Manuaras, I spend my time in the peripheries of the city, Jorge Teixeira, Sao Jose Operario, and Compensa. Here, I am interviewing workers, mostly women, who work for television set factories. Outsiders to these neighborhoods cannot imagine where I am aside from the usual stereotypes of jungles and Indians or slums and criminals. When Hurricane Katrina flooded my city of New Orleans and occupied the news media here for more than a week, however, insiders no longer understood where I was from.

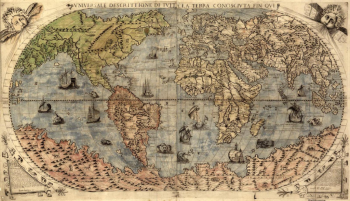

Old World Map

I see the satellite image at the cyber-cafe cross the street from the hotel I have called home for the previous month. The swirls of red and green are moving towards a dislocated peninsula somewhere in the United States. The map seems as foreign to me at that moment as the culture of the city I was calling my temporary home.

There’s a hurricane coming, I tell a group of women casually at a sewing collective for unemployed factory workers. It is the Friday pre-Katrina.

Quizzical responses. You get those a lot, no? That’s just a lot of rain, right? They shrug, reminding me of the way longtime New Orleanians have done the same every rainy season.

I try to punctuate the words. No but it’s so big it could destroy the entire city. More shrugs and perhaps an attempt to sympathize. We get a lot of rain too. You should be here from December to June.

“What did she say?” another asks the room.

Some kind of earthquake in her city, responds the first.

*****

Monday I am at the offices for a local newspaper looking at archive photos for my project. In my selections, workers smile through empty TV cabinets on the assembly line. They will reproduce well, I think to myself. Images seem to cajole us into thinking that we can understand a context anonymously. A journalist asks if he can do a short article on me and Katrina.

“What is a levee?” the novice writer asks.

“It’s like a dam, but it looks like a big hill that protects the city from water.” I don’t know how to translate this word.

Sounds very advanced.

“I’m afraid it won’t work and people will die.”

Are you sure that people will die or just afraid people will die? He is trying to clarify my meaning, but he can’t understand. He faces the computer screen as he types and retypes my words. “But you have no family there.”

“But I have my friends, my work, my house,” I justify.

I went back to the cyber-cafe. Two more levees broke and the city has been filling with water all day.

Tuesday morning the newspaper story takes about one-fifth of a page inside. There is a profile shot of me, tan and smiling, like the women behind the TV cabinets. The article read, “She had no family here.” His notes meant that I was not really from there.

*****

The beginning of the week and New Orleans news now dominates Brazilian media over reports of widespread government corruption. Our hurricanes are different, repeat several observers to me. Despite the lack of all communications in the city, Brazilians become completely fluent in the details of Furacao Katreeennaa. The cyber-cafe owner explains the topography of New Orleans to me and the problems with budgetary funding for the levee system. The sewing group recites to me the differences between a Category 4 and a Category 5 storm. Meanwhile it has not rained in the Amazon for months, causing the most dire drought there in 60 years.

In contrast, I continue to be hopelessly ignorant. Four nights and counting, I’m watching CNN (I can’t watch this in Portuguese). I gasp at what I think I recognize. I know that intersection, that building, that neighborhood. But what about my street? My apartment? I have to struggle not to fill the void in my head with the reports of looting, mayhem, and death. This happens every hour as the same images are re-broadcast. I want to save the outdated satellite images of my building from Google Earth as a momento.

*****

Still Brazilians “know” that the U.S. is rich.

“How are you doing?” asks a concerned university professor here at the federal campus.

“I think we may have lost everything,” I sigh.

“Oh but the insurance will pay.”

“I don’t have insurance.”

“Then the government will just give it all back to you.”

The prime-time telenovela passing on the television now is America. Set in against a colorful yet gleaming Miami skyline, the Americans that Brazilians imagine continue to be blessed with easy fame and fortune. Even when the furacao came into the storyline, it brought gentle rain and a light breeze.

*****

Thursday I go to a city-sponsored fair where the sewing group sells their crafts. They have not sold anything today and middle-class people sniff at the prices. The woman that everyone refers to as the happy one, talks to me for the first time since I met her three weeks ago.

“I lost my house last April. We were sleeping when the rains eroded the wall holding it. I’ll never forget the noise. Pieces of the house started falling down the hill. I left with the kids but my husband was trapped in a part where the roof collapsed. The room was filling with water. When my cousin came, he broke through the metal and gashed his foot. When we got to my husband, the water was up to his neck. We survived.”

“And your house?” I ask.

“We lost everything. We live with my mother.”

I take inventory of the luxuries I have in my hotel room: hot water, cable television, and an air conditioning unit. I am not from Miami, nor from Manaus.

*****

New Orleans Under Water

For me, news bytes become ironic ways of seeing similarities and differences between two cultures that misunderstand each other. On Friday both Manaus and New Orleans are 36-degrees Celsius with over 80 percent humidity. In the former, 80 percent of the city was without water after a power generator that fed the water company had to be shut off. In the latter, 80 percent of the city was under water according to the Mayor. This means that in both cities, bodies are dirty and thirsty. I roll the blue anti-malarial pills around in my hand after a CNN reporter cites the possibility of malaria in Louisiana. Here, the papers cite the highest incidences of malarial deaths in eight years. And I have not even been bitten.

Before the hurricane, I made a class presentation to a university extension class in the periphery. In the question period, a returning student asked what it was like to come from a developed country to an underdeveloped country.

“I don’t like those terms,” I parried in my best professorial voice. Some have called Brazil “Belinda,” part-Belgium, part-India. I think that in some ways Manaus is very developed. To demonstrate, I asked them how many of them owned cell phones. All hands in the classroom of working class people rose affirmatively.

A week later, though, I get the response that the student was expecting. The continuous blog for the New Orleans newspaper reports that my city has lost all modern communications, electricity, and potable water. New Orleans has become a Third World city.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

It is interesting to know how the world can sometimes reflect upon American issues as we so often reflect upon the issues of the world. Though people with genuine concern and just as much heart as any other, is a problem is distant, it is often just not real. Intersting, however, to read about reports recieved in other areas of the world about the tragedy- especially with rumors circulating as to what did and did not happen, and questions of journalistic integrity in the field.

The correlation, however, between economic structure and response to foreign issues seems less inherent than a distance issue. Though certainly shaped by the ideas of American prosperity and success, the flippant nature was one often had by American working class citizens. It seems, once again, that a subject can’t truely hit your heart unless it hits your home.

Developed vs. Developing

I think the difference is that if a hurricane had destroyed a third-world city it would have taken up maybe 5-10 minutes of news coverage in the USA and most of the world, rather than the weeks of continuous coverage that were taken up by Katrina in New Orleans. Take for example the earthquake in Pakistan, which was far more devastaing in terms of casualties and property damage. While it was covered extensively by most media organizations in the US it nowhere reached the amount of global coverage that Katrina did.